Bowen's taking us for a ride

Do we have no original ideas in this country? The ink had barely dried on Energy Minister Chris Bowen's new vehicle emission standard requirements before it was revealed that US President Joe Biden is about to relax his own country's new emission standards requirements – on which Bowen's are based. And a future President might remove them altogether, as Trump did last time he was in office.

Emission standard requirements are a funny one; a far from optimal solution of reducing transport emissions, a task at which they often fail anyway. For example, did you know that a reason so-called "Yank Tanks" proliferate so widely in the US is because of emission standard requirements? In a classic case of good intentions meeting the brick wall of unintended consequences, the original 1975 emission rules included a vehicle footprint to avoid punishing specific automakers that offered both large and small vehicles. Larger vehicles, such as light trucks used on farms, would face less ambitious fuel-economy targets than smaller cars. So what did automakers do? They gradually made their vehicles bigger, designing more of their "cars" with light truck frames:

"The result is a loophole, allowing the entire auto industry to sidestep some of the more painful efficiency requirements by inflating vehicle footprints. And historically, drivers almost always lean toward larger vehicles. 'In general, if everything else about the vehicle is the same, consumers prefer the bigger one, with the roomier interior,' says Kate Whitefoot, a senior program officer at the National Academy of Engineering and the lead author of the paper. Combine a regulatory loophole with a built-in, well-known customer choice, and the industry lurches towards the inevitable: larger models and more light trucks."

Even the amendments to the rules made by the Obama administration "make it easier for US automakers to give customers what they want and to keep expanding the size of their vehicles", with an 8 square foot increase in size allowing for 2-3% more emissions.

But back to Bowen's policy. I've been meaning to cover it for a while, given Bowen's rather bold claim that it will allow families to "save about $1,000 per vehicle per year". I'm generally suspicious when someone claims that a regulation will lead to lower prices, especially when the stated purpose is to discourage the thing being regulated by raising prices. I mean, I guess if you banned all cars then you could technically claim that you're "saving" the average motorist the $5,000 they spend each year on petrol, but that's not exactly being honest, now is it: our welfare would clearly decline by a much greater amount.

Generally speaking, if consumers aren't already demanding vehicles with the fuel efficiency Bowen is trying to achieve then there must be reasons why, such as a higher upfront cost, performance, aesthetics, safety, or other features. Good policy making should consider all of the possible reasons before drawing conclusions.

Digging into Bowen's emission standard requirements

One reason I wanted to dig into Bowen's claim is because he's not selling this purely as environmental policy, but also as a cost of living relief measure:

"Because of a lack of action on an Efficiency Standard, Australian families are paying around $1,000 a year more than they need to be for their annual fuel bill – the Albanese Government is delivering long-term cost-of-living relief to fix that for new vehicles and put money back in people's pockets.

We're giving Australians more choice to spend less on petrol, by catching up with the U.S – this will save Australian motorists $100bn in fuel costs to 2050.

This is about ensuring Australian families and businesses can choose the latest and most efficient cars and utes, whether they're petrol and diesel engines, or hybrid, or electric."

Notwithstanding the fact that we will now be moving ahead of the US on vehicle emission standards rather than "catching up", this quote from Bowen looks to be a fine example of Orwellian doublespeak; a rule that raises prices and restricts consumer choice is being sold as the opposite!

"War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength."

So just how did Bowen get his $1,000 figure? I followed the link provided in the media statement, which after a few clicks led me to a Department of Infrastructure impact analysis. The Department modelled three options, with "Option B" their preferred and the one that Bowen selected. Everything that follows will focus on that option.

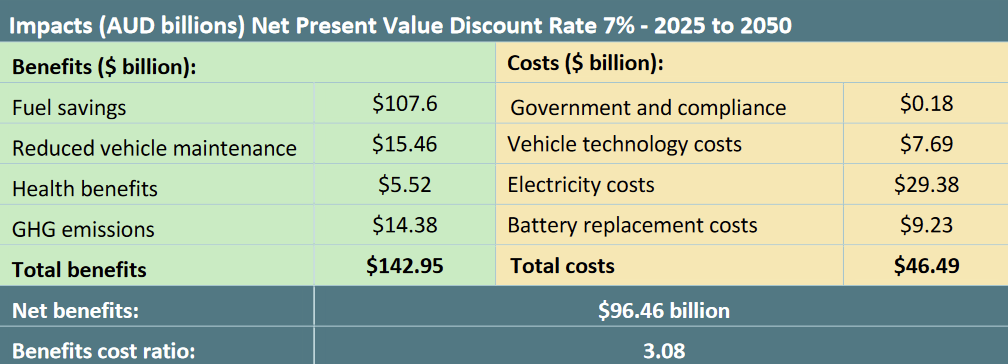

The first thing that stuck out to me was that the $1,000 saving only applies to those buying new cars in 2028, who "will cut their fuel costs by around 40% compared to what they pay today". That number appears to be derived directly from the estimated benefit of $107.6 billion in fuel savings over 25 years less electricity costs of $29.38 billion. Here's what the table looks like:

Notice that only some of those benefits are for the individual – fuel savings and maintenance – while others, such as GHG emissions and health benefits, are societal (this distinction is made later in the report on page 47). However, all of the costs fall on the individual. Simply adjusting the table for the individual – remember, Bowen is selling this as cost of living relief, not just environmental policy – and the benefit cost ratio (BCR) falls to 2.65.

Digging further into the report, the government's analysis included a discount rate of 7% to account for inflation and the time value of money (people prefer a dollar today to a dollar in the future). Fair enough; perfectly standard.

But perhaps the most important assumption used in this exercise, given Bowen's claim was purely about "fuel savings", is what will happen to petrol and electricity prices. Thankfully Appendix B provides an assumption: real petrol prices will rise from $1.76/litre to $3.93/litre by 2050 (a 223% increase). The source listed for that assumption is the IEA World Energy Outlook data 2022, which forecast a 37.7% increase in real oil prices between now and 2050 (petrol prices are strongly correlated with Brent crude prices in Australia).

There are a few issues with this methodology. First, the IEA report was out of date by the time the government concluded its BCA in early 2024; the base year used was 2021, not 2023. Oil prices rose 16.4% between 2021 and 2023, accounting for roughly half of the IEA's projected increase. Adjusting for cumulative inflation in those years brings the real increase down to around 15%, leaving real growth of just 16.6% required to reach the IEA's 2050 forecast.

At this point, I know some of you might be wondering why the IEA assumed such a small change in the real price of oil, given the ongoing decarbonisation of the planet. But remember that as the world moves towards renewables and electrification and away from oil, it will affect both quantity demanded (fewer uses for oil) and quantity supplied (fewer oil wells). Oil prices could plausibly move up or down, depending on whether emission reduction is driven by demand- or supply-side policies.

If the Department used a more moderate real oil price assumption such as the one provided by the IEA, rather than assume a large 223% increase, it would also be consistent with its forecast of real electricity prices, which it assumed will decline 0.16% annually (so ~4% over 25 years) despite the implied increase in demand as people transition away from oil and gas.

Using the IEA's forecast instead of the Department's gives $1.76/litre * 1.166 = a $2.05/litre petrol price by 2050, not the $3.93/litre assumption used in the Department's BCA. Again, these are all in real dollars: all values need to be converted to current dollar terms to be comparable in a BCA. Using an assumption of $2.05/litre by 2050 knocks $1.88/litre off the Department's estimated fuel savings – almost half.

The BCR now falls to 1.54.

But wait, you say! What about all those motorists who might prefer to drive an ICE vehicle for various reasons; fuel efficiency standards will clearly leave them worse off. Why wasn't that included in the BCA?

Why indeed. For whatever reason, the headline BCR cited by Bowen completely omits the impact on consumer welfare, or the deadweight losses caused by the policy change.

And that's a big deal.

For example, you could ban all ICE vehicles tomorrow and the BCR, using the Department's methodology, would be astronomically positive. But consumers would clearly be worse off – demand hasn't fallen, just quantity demanded; people would still want to buy and drive their ICE vehicles just as much as they did before the ban, but they wouldn't be able to. There's no preference change here, so the deadweight loss is equal to the potential gains from trade that will now never be made.

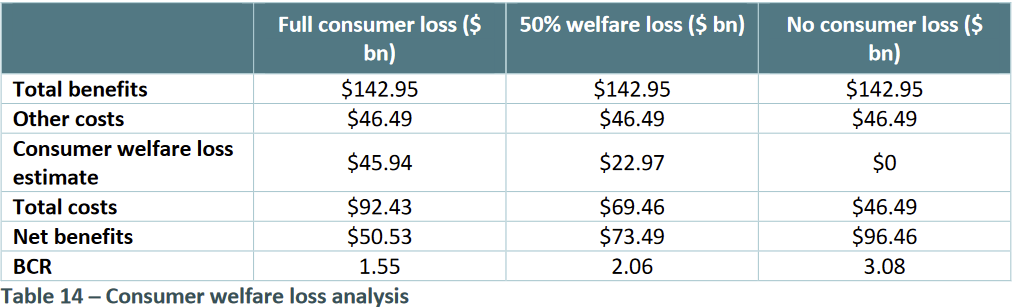

Thankfully, the authors considered consumer welfare later in the report:

This is where we get into very murky waters. The modelling has not been provided, just a single text box on page 50 describing the methodology. Unlike the variables in the headline BCR, there are no assumptions in the appendix. The text box only indicates that the authors have added an assumed improvement to consumer welfare due to shorter wait times and lower EV prices, while subtracting a consumer loss for those who prefer ICE vehicles "for a reason despite all of the financial benefits (i.e. fuel savings, lower maintenance costs etc)", to come up with a new BCR.

Understandably, the welfare assumptions have strong caveats, warning that they are "subject to a whole range of variables that may not come to pass, and in particular, that the baseline adoption rate might be exceeded, or that consumers underinvest in fuel efficiency (partly due to incomplete information)".

Why wasn't this important cost included in the headline table? I don't know. But the more I read of this report, the more likely it seemed that the outcome was predetermined. Take the use of the phrase "that consumers underinvest... partly due to incomplete information"; they may as well have said "consumers might prefer large ICE vehicles, probably because they're uneducated".

But the authors of the report were wrong to doubt consumers. Economists know that consumers "are able to make rather complex choices with a great deal of rationality", even during an energy crisis. But if consumers are relatively rational – say, boundedly rational – that would undermine Bowen's claim that "because of a lack of action on an Efficiency Standard, Australian families are paying around $1,000 a year more than they need to be for their annual fuel bill".

For Bowen's claim to be true consumers must be irrational – why else would they still be choosing ICE vehicles over NEVs, despite the financial savings they could be enjoying?

But back to the numbers. If we take the provided "full consumer loss" as a given (without the Department's full workings I can't be sure what they did) and subtract it from the above, the BCR drops to 0.55, i.e., to nearly half the estimated costs. Even subtracting just the 50% welfare loss scenario, which would be a huge assumption to make given how perturbed people are by this change and how popular ICE vehicles are in Australia today, the BCR drops to 1.05: barely above 1.0.

This may be the sixth, seventh or fourteenth best way of reducing emissions

I can't be sure without seeing their workings but the impact analysis definitely has flaws. Deliberately misleading? I'm not sure, but the way the report discusses consumers and the rather extreme petrol price assumption they used leads me to believe that may be the case. How else can you explain why social welfare would not be included as part of the main BCA but buried on page 50 with no further discussion and no assumptions in the appendix? Why the modelling is still being kept secret?

As for Bowen's $1,000 claim, it's demonstrably false. The only way you can make that claim with a straight face is by ignoring most of the costs in the BCA.

The scheme will also fail to put "money back in people's pockets", given that it works by forcing manufacturers to average a certain efficiency across their fleet, which they do by raising prices on certain vehicles to reduce quantity demanded, while lowering prices on more efficient vehicles. As a result, the price of many vehicles Aussies love – e.g., utes used by many blue collar workers such as the Ford Ranger and Toyota Hilux – will increase significantly.

Surely that, and the accompanying welfare loss, must be included in any honest estimate of costs and benefits?

Then there's the fact that the stated benefits only apply to those who buy a vehicle in 2028, i.e., once the changes have fully kicked in. But people don't buy vehicles all that often: around 1 million new vehicles a year. The 2021 Census counted 1.8 vehicles for each of our 9.275 million households, so it would take over 16 years to replenish that stock. Even if Bowen's claim stacked up, only a fraction of Aussie households would be "saving" that $1,000 worth of fuel costs.

Another omission from the modelling exercise was the potential for behavioural changes. If people really like ICE vehicles but can't or don't want to pay the extra few grand for a new vehicle, they might hold on to their older, less efficient and less safe vehicles for even longer, undermining some of the benefits (this is known as the leakage effect).

Further, the report doesn't discuss possible alternatives. Academic research on the US version of this scheme has found that "a fuel economy standard is shown to be at least six to fourteen times less cost effective than a price instrument (fuel tax) when targeting an identical reduction in cumulative gasoline use".

The reason why Bowen's plan is so much worse than a simple fuel tax is because of the incentives: while a fuel tax would provide immediate, direct incentives to reduce their usage of petrol (whether it's driving less, or upgrading to a more efficient vehicle), efficiency standards only apply to new vehicles. Perversely, by making vehicles more efficient and cheaper to operate, they also incentivise people to drive more, not less (this is known as the rebound effect) – not exactly consistent with the public transit-oriented outcome our central planners claim to want.

Then there's the risk that we might be forcing people to change before the charging network is ready; before most of our renewables are online (so we're not burning dirty coal to power NEVs); and before unsubsidised electric vehicle costs come down to justify their purchase over an ICE alternative. These are all potential costs that, as far as I can tell, were not incorporated in the BCA.

Don't get me wrong: I'm not some anti-EV Luddite. I drive an EV, which I charge using solar from my roof. But I also don't pretend that my use case is typical; I'm a desk jockey, not someone who might be driving from job site to job site carrying a tray full of cargo. An EV works for me, but it's not going to work for the plumber down the road – certainly not by 2028, anyway!

As Mitsubishi Motors Australia CEO Shaun Westcott put it:

"The reality is at the moment – the F-150 Lightning [electric ute] is thrown around very loosely – in the same statements they talk about 'we hope to see these in our constituency' and 'we hope middle-class Australia will have these'. Well, the reality is if anyone has bothered to price an F-150, they're far north of $100,000 – that's not middle Australia.

The second aspect of that is that technology – and there are significant studies done out there – when you put a real payload on that thing or when you tow, then suddenly there's 125km range on that thing. If you're a tradie doing work out there [in regional Australia] you're going to travel more than 125km – you've got a problem.

If you're a tradie with a tray's worth of tools, or bags of cement or tiles… suddenly those are realities that need to be faced in terms of 'what do Australians need and what do Australians what?' And, how are you going to provide them, and do you have the ability to offset?"

Australian cities are some of the least dense in the world; that means we have to drive a lot. We're also a tiny market, so it will take time for NEVs to develop to meet the specific requirements that we face in this country, especially if the US has already given up on its version.

What Bowen should have done

In public policy, the "relevant choice is between alternative real institutional arrangements". On the list of things to do about carbon emissions and the cost of living, fuel efficiency standards are one of the more costly, inefficient and unwise arrangements available.

The best arrangement to cope with the problem of carbon emissions would be a revenue neutral, economy-wide carbon tax, but if that's politically impossible then a second-best option to reduce transport emissions would be to raise the excise tax on petrol and diesel, with the extra revenue raised distributed to households in the form of a dividend, minimising the deadweight loss of the tax.

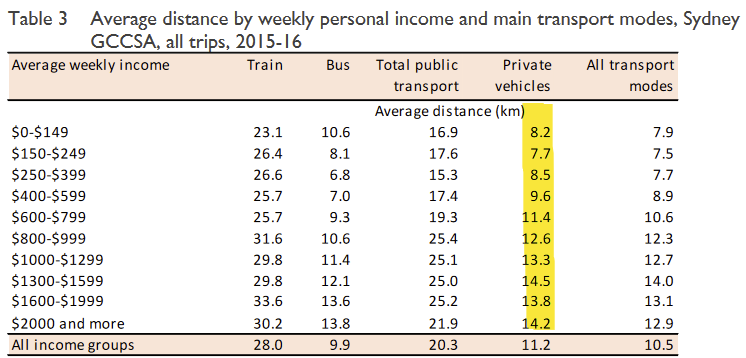

With a higher price of petrol, many families might prefer to drive a bit less – or buy a more efficient vehicle – and spend their dividend on something else. It would also be relatively progressive: in Australia, people on higher incomes own more private vehicles per household and drive further on average than those on lower incomes.

A higher tax on petrol and diesel would still provide a competitive advantage to energy efficient and cleaner vehicles, reducing emissions, while also helping to ease the cost-of-living crisis for those on lower incomes, given they would receive the largest dividend as a share of their incomes. Better still, manufacturers could still sell the cars people want, more closely reflecting their preferences, and there would be no rebound or leakage effects.

But instead of choosing an efficient tax, Bowen decided to take us all for a ride, promising benefits while conveniently ignoring the costs, hiding his work and hoping we're all dumb enough to simply take his word for it.

Australian policy making at its finest!

Member discussion