Friday Fodder (18/24)

1. A pocket full of poison?

According to a new book called The Anxious Generation by psychologist Jonathan Haidt, smartphones and social media are doing serious harm to our youth, especially young women:

"Haidt blames the spike in teen-age depression and anxiety on the rise of smartphones and social media, and he offers a set of prescriptions: no smartphones before high school, no social media before age sixteen."

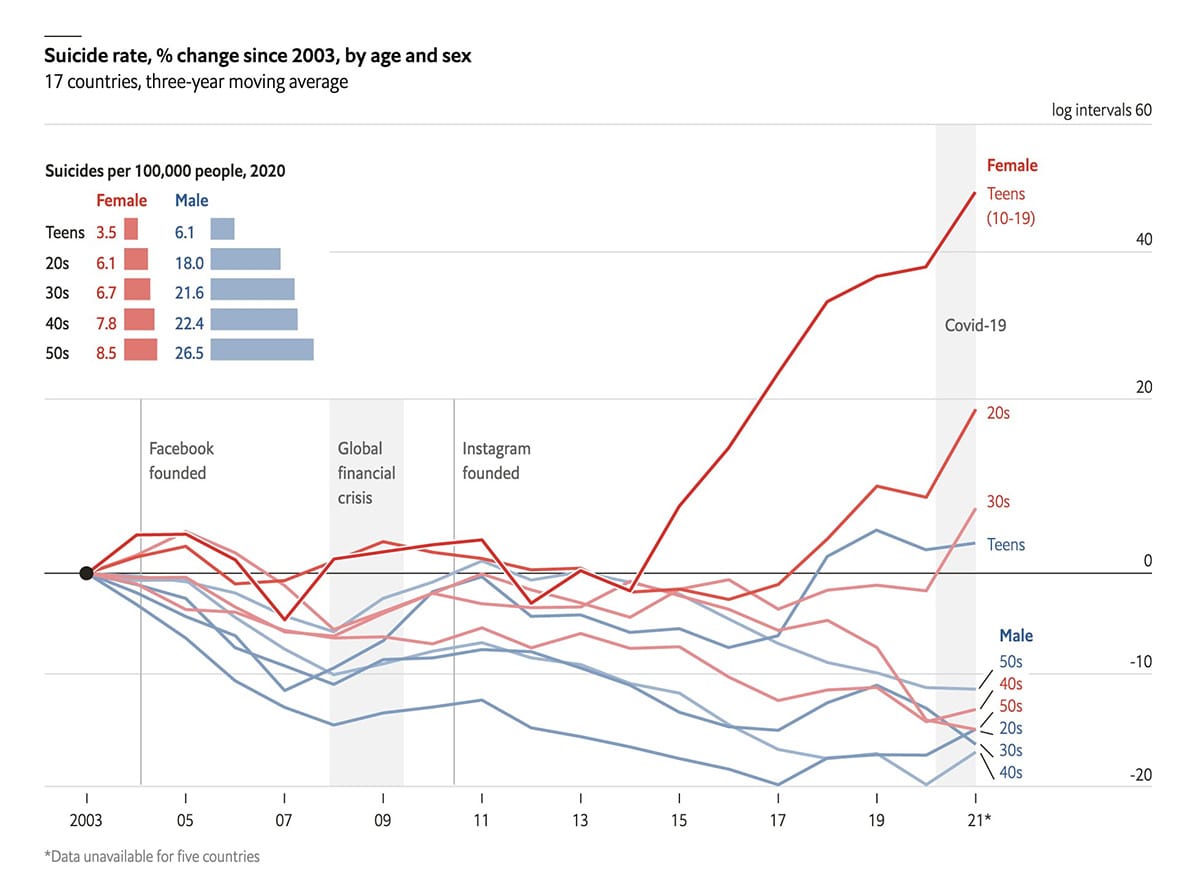

Haidt draws from survey data to show a correlation between smartphones, social media and social ills, including teenage suicides. Charts like this would appear to confirm his theory:

But as every good statistician knows, correlation is not causation and percentage changes can be misleading. In this particular chart, the "surge" in teenage girl suicides is mostly due to a very low base in 2003: girls were, and still are, far less likely to commit suicide than boys (the bar chart in the top left). Suicides by girls ages 10-19 are relatively rare events (at least compared to boys or older demographics – men in their 50s have a suicide rate more than seven times as high), so a small increase can cause a spike in percentage terms.

The NYT's science writer David Wallace-Wells went even further, penning a well researched antidote to the sensationalism:

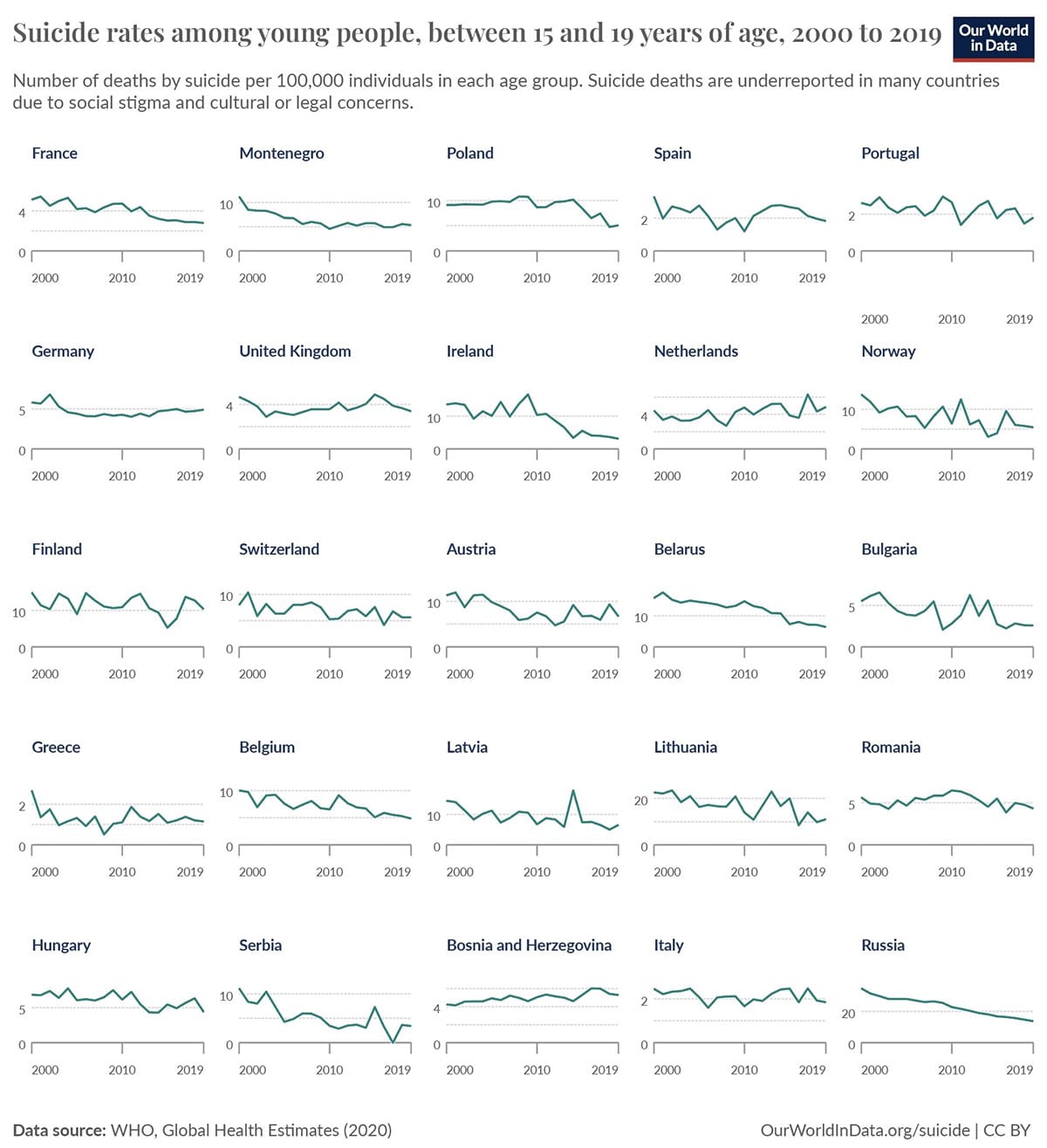

"In some countries, we see concerning signs of convergence by gender and age, with suicide rates among young women growing closer to other demographic groups. But the pattern, across countries, is quite varied. In Denmark, where smartphone penetration was the highest in the world in 2017, rates of hospitalization for self-harm among 10- to 19-year-olds fell by more than 40 percent between 2008 and 2016. In Germany, there are today barely one-quarter as many suicides among women between 15 and 20 as there were in the early 1980s, and the number has been remarkably flat for more than two decades. In the United States, suicide rates for young men are still three and a half times as high as for young women, the recent increases have been larger in absolute terms among young men than among young women, and suicide rates for all teenagers have been gradually declining since 2018. In 2022, the latest year for which C.D.C. data is available, suicide declined by 18 percent for Americans ages 10 to 14 and 9 percent for those ages 15 to 24."

Looking at the data, most European countries have seen steady or declining rates of suicide among young people over the past couple of decades:

Wallace-Wells also found some issues with Haidt's data itself:

"Haidt likes to cite data collected as part of an international standardised test program called PISA, which adds a few questions about loneliness at school to its sections covering progress in math, science and reading, and has found a pattern of increasing loneliness over the past decade. But according to the World Happiness Report, life satisfaction among those ages 15 to 24 around the world has been improving pretty steadily since 2013, with more significant gains among women, as the smartphone completed its global takeover, with a slight dip during the first two years of the pandemic. An international review published in 2020, examining more than 900,000 adolescents in 36 countries, showed no change in life satisfaction between 2002 and 2018."

A rise in social and health issues among young people is certainly worth investigating. In this case, the culprit for the "surge" – at least in the US – appears more likely to be the result of new bureaucratic guidelines that required hospitals to record self-harm more accurately. According to Wallace-Wells, those "changes explain nearly all of the states apparent upward trend in suicide-related hospital visits, turning what were 'essentially flat' trendlines into something that looked like a youth mental health 'crisis'."

Food for thought before we blame the latest technology for whatever might be ailing us at the time.

2. Praying for rain

Two states, Victoria and Western Australia, released their 2024-25 budgets this week. I'm not going to go through them page by page; there's plenty of media coverage about all the changes and various handouts (e.g. here and here).

But what I found interesting is that both state governments managed to spend themselves into a deficit – that is, accounting for all spending and revenue, not just their operational requirements – despite recording annual revenue increases of 8.1% and 3.4% in 2023-24, respectively, from already-high bases (the pandemic was very kind to government revenue).

They're rolling in cash, yet instead of exercising spending restraint and paying off debt, they seem to prefer using most of their energy arguing about how they're getting screwed by the Commonwealth's GST distribution (seriously, Victoria dedicates an entire feature box to it on pages 70-71 in Budget Paper 2).

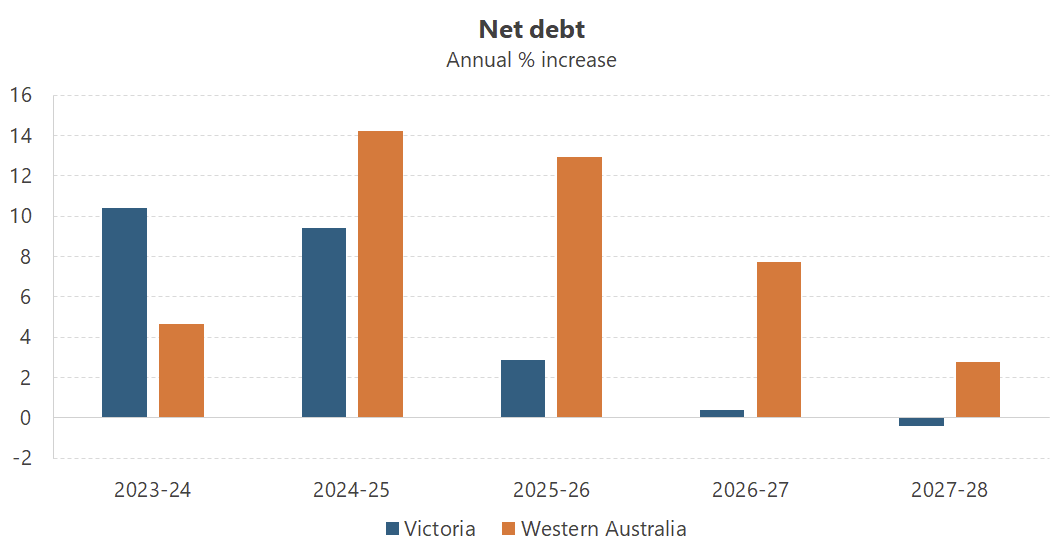

As a result, net debt will continue to increase in both states across the forward estimates.

The projected increase in net debt in WA is especially concerning, because while the level of debt is well below VIC's, it wasn't that long ago that VIC had a debt to GSP under WA's forecast of 8.2% for 2024-25 (e.g. 5.1% in 2018-19). Sure, WA is still cashing in on volatile iron ore royalties that allow it to run operational surpluses and, should prices stay elevated, is making their net debt projections look worse than they are. But prices have crashed before and they may again; as VIC showed, it doesn't take long to go from the best in the country to the worst.

Speaking of the worst, VIC – the lowest-rated state in Australia – has again been put 'on notice' by ratings agencies, with any further downgrades to make its debt position increasingly perilous. And despite Treasurer Tim Pallas claiming that he's "not sitting back praying for rain", that's exactly what he's doing: hoping that interest rates "come down over the next four months", taking some pressure off his stressed books. Good luck with that!

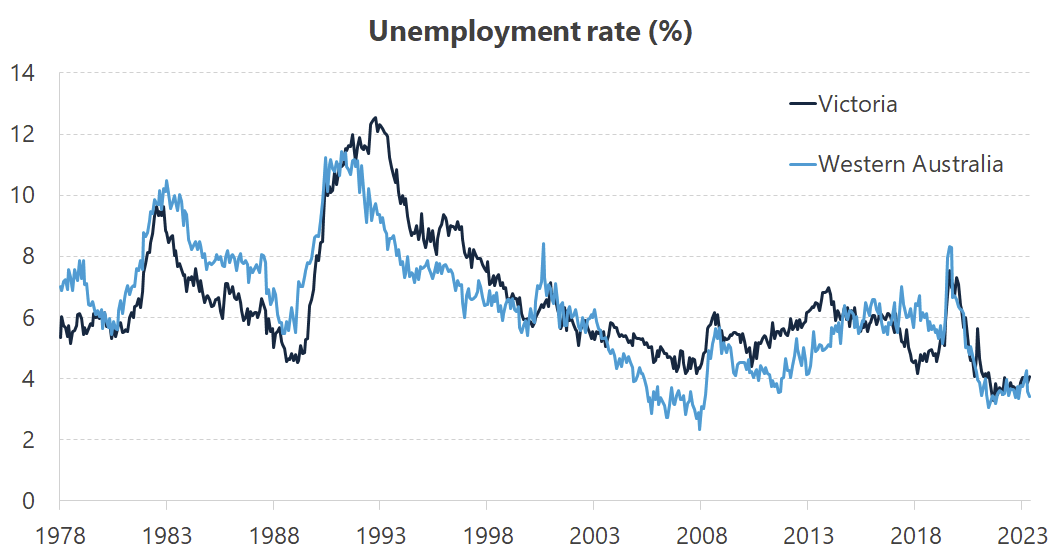

But what really irks me is there is no good reason for such fiscal profligacy in either state. It's just not the time for cash handouts, and while it's true that both are spending significant sums investing in fixed assets, it's not clear (1) that much of it is needed (e.g. WA is expanding heavy loss-making Metronet lines to the low-density outer suburbs, while VIC's Suburban Rail Loop fails any reasonable estimate of costs and benefits); and (2) that much of it is needed now (unemployment rates have been at, or close to, all-time lows in both states for nearly three years).

On that point, by running headline deficits these states are actively bidding resources away from the private sector, which is struggling to build other things people want, like houses. Here's Victoria stating as much in its Budget:

"The [housing construction] sector continues to face labour constraints, as shortages of skilled trades limits the amount of work that residential construction firms have been able to complete.

...

Spare capacity in the overall Victorian construction workforce is very low, as it is in New South Wales and nationally. Infrastructure Australia's 2023 Market Capacity Report estimates that demand for workers exceeds the current national public infrastructure workforce by 129 per cent.

Occupations such as construction managers, electricians, plumbers, painting trades workers, and carpenters and joiners are in particularly high demand."

With solid economic growth and low rates of unemployment, every state in Australia should be making hay while the sun shines, running headline surpluses and taking some pressure off the Reserve Bank of Australia's need to hike rates again.

Sure, population has increased, justifying some additional expenditure. But not this much! The fact is our states are addicted to spending, even during the good times. That's all well and good until it isn't, and we wake up one day only to realise we have no fiscal capacity to respond to an actual crisis because they spent it all during the good times.

If only we had some fiscal rules to keep them in check...

3. Running on empty

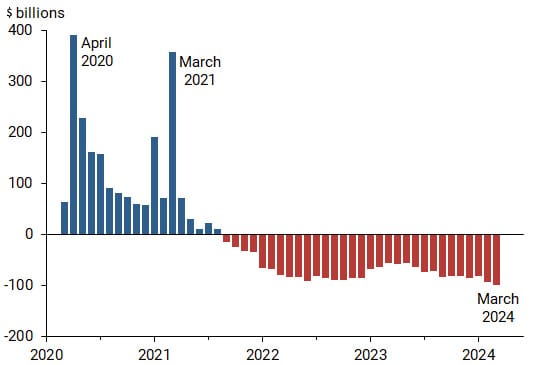

The pandemic transferred a lot of (borrowed) cash from the government to households, which not only fuelled inflation but has also helped support consumption as interest rates rise. I'm not aware of any decent data on what's going on in Australia, but over in the States it looks as though the yanks have finally depleted their stash of pandemic savings. At least according to a new research report by the US Fed, which included these charts:

The authors ponder what might come next:

"[T]he depletion of these excess savings is unlikely to result in American households sharply cutting their spending levels as long as they are able to support their consumption habits through continuous employment or wage gains, other forms of wealth—including non-pandemic-related savings—and higher debt."

In other words, the Goldilocks recovery. So long as everything stays just right, then the lack of a savings buffer shouldn't deter consumers going forward. Gulp.

4. This is where industrial policy leads

The European Union (EU) wants to go green. China is selling it a bunch of cheap, green wind turbines. But – shock, horror – it turns out the EU never just wanted to go green; it also wanted to make all the stuff needed to go green:

"We can't afford to see what happened on solar panels happening again on electric vehicles, wind, or essential chips."

That quote is from European Commission Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager, who last month opened an inquiry into Chinese suppliers of wind turbines.

But the fact of the matter is the Chinese are just really good at manufacturing stuff, due to a combination of a lighter regulatory touch that fosters competition, subsidies (of course), and:

"Proximity to inputs at every stage of the supply chain — from steel to advanced rare-earth magnets, a market that China also dominates — creates agglomeration effects for Chinese producers that are hard to replicate."

That's from Nicholas Welch of China Talk, who notes that it's not all China's fault; Europeans aren't great at manufacturing:

"[A] fair share of the blame for the decline of European producers lies at the feet of the producers themselves. Most notably, Siemens Gamesa has had ongoing problems with quality for two of its onshore wind turbine platforms, the 4.X and 5.X, forcing the firm to go to the German government for what ended up being a $8.1 billion bailout. It's currently engaged in similar discussions with the Spanish government — little wonder, then, that Goldwind has announced it is looking into potential energy projects in Spain, one of the countries on which the Commission's inquiry will focus."

Unlike Chinese industrial policy which tends to permit "fierce competition" (at least compared to the 'picking winners' strategy favoured in the West), the EU insulates its domestic industries, leading to complacency. That then leads to more protectionism, undermining their goal to decarbonise:

"According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Chinese turbines delivered outside of China cost an average of 20% less than those made by European and American counterparts. Turbine prices within China dropped 11% in 2023. Especially for countries with no developed wind suppliers, these are meaningful cost reductions, which very well could pencil out previously infeasible investments in new wind capacity."

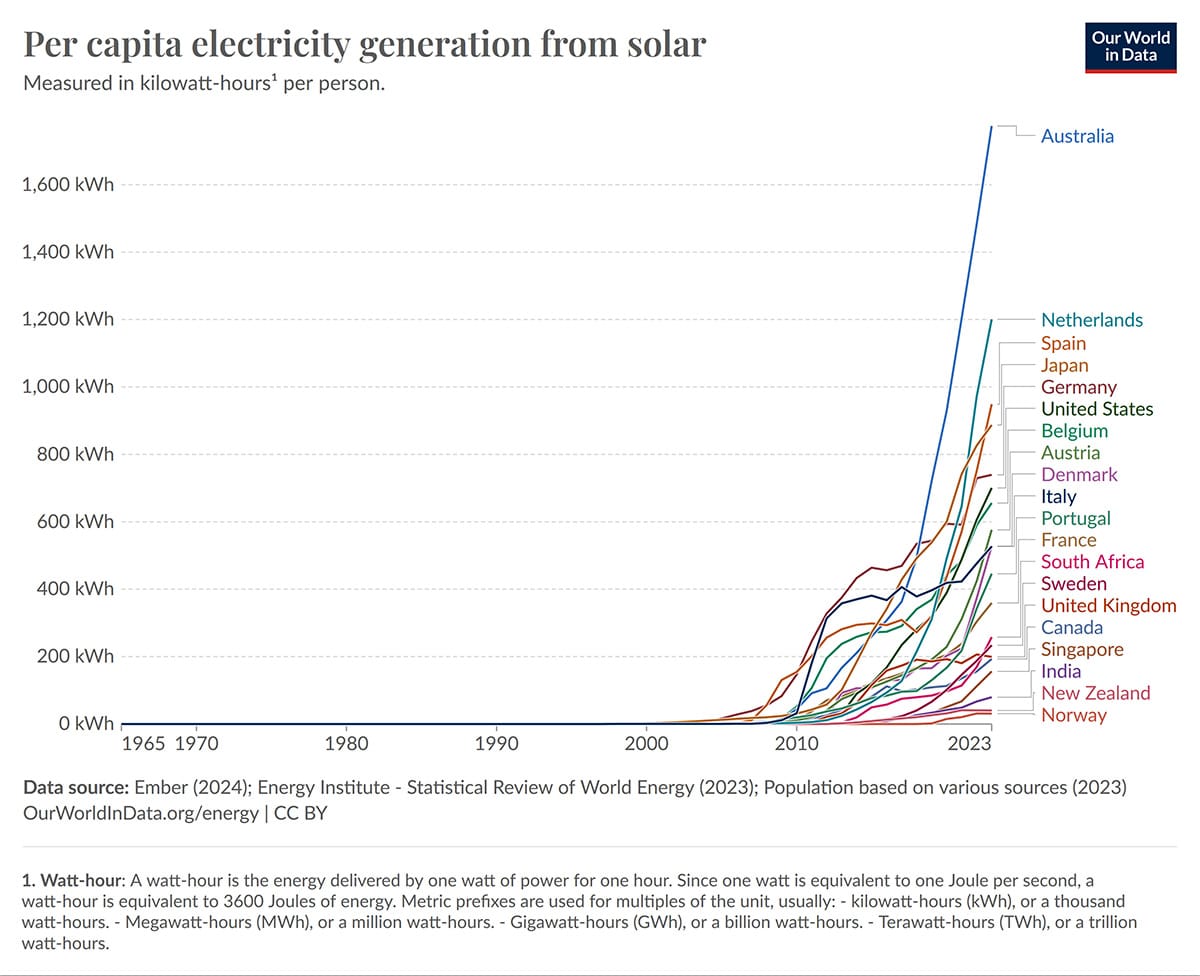

Anthony Albanese, take note. We should be importing cheap Chinese solar panels, EV and wind turbines, rather than trying to make them here at great cost. China's industrial policy is very wasteful – "widespread subsidisation [is] followed by a process of consolidation within China, causing suppliers to turn their capacity toward external markets to scrape by any margin they can get outside of China" – and Australia should take advantage of that by buying their stuff on the cheap, as we did with solar panels!

Just imagine how much further down this chart we would be if, instead of importing panels from China, we had to make them all in the Hunter Valley.

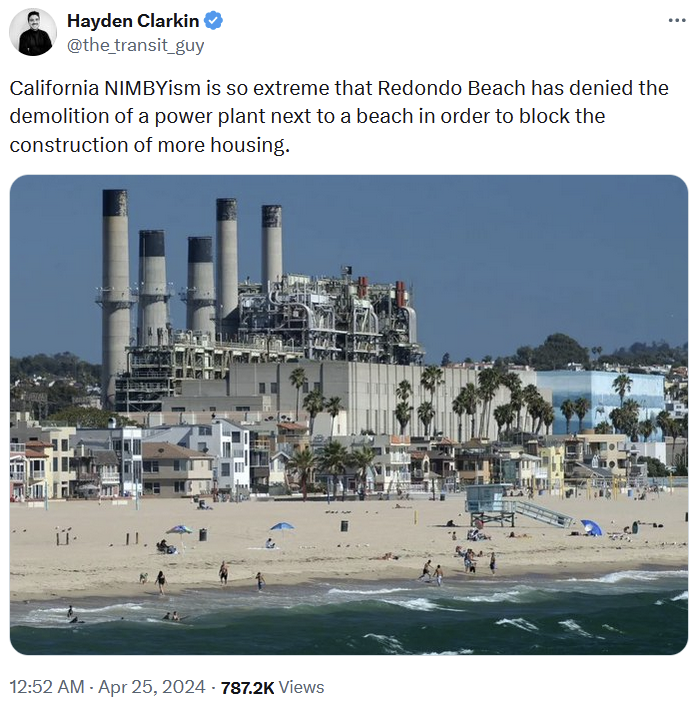

5. Can't afford a house? It could be worse

We may have some questionable zoning laws that prohibit housing construction in this country. But it could be worse; we could be California.

6. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

What's up with Japan? – The yen's collapse has made Japan a tourist hotspot, but it has also sparked crisis fears. While a full-blown crisis is unlikely due to Japan's relatively low interest costs and its ability to raise taxes, an ever-aging population and repeated policy missteps are only increasing the risks.

Albo's HECS changes: fairer and cheaper, or regressive and expensive? – Rather than fairer and cheaper, Albo's HECS changes will make the scheme more regressive and expensive, benefiting middle-to-upper income households, distorting work-study incentives, and failing to address real barriers faced by disadvantaged groups.

Have a great weekend.

Member discussion