Friday Fodder (21/24)

1. It was never going to last

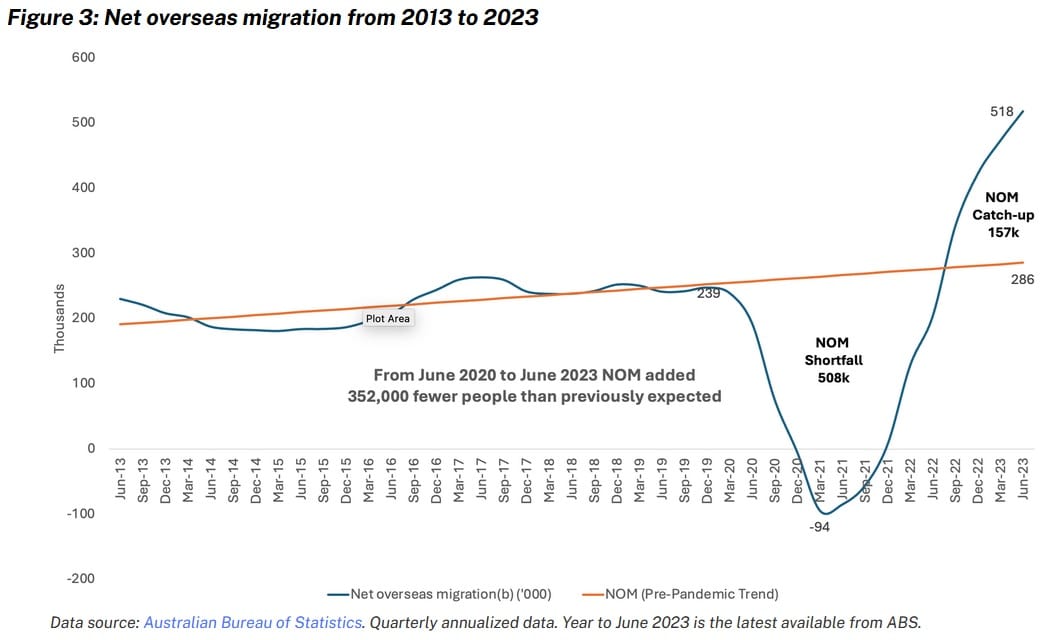

I've written a few times about why the post-pandemic migration surge was always going to be temporary, and that in the context of our other problems they don't matter all that much. So I was pleased to see a little explainer on the "surge" from ANU, which covered what is basically a statistical quirk that the media and politicians have made into something far more than it is:

"NOM is just arrivals minus departures. So, there are two ways NOM can grow: arrivals increase, or departures shrink. And as we’ve just shown, arrivals haven’t grown.

However, departures did shrink during COVID, because the Coalition Government extended temporary visas. That meant fewer people on temporary visas departed from Australia.

These extensions have not all expired yet. As a result, departures are still at historic lows (Figure 2). From June 2020 to June 2023, there were 334,000 fewer migrant departures than previously expected."

"When we add the small recent arrivals rebound to the prolonged shortage of departures, we get the recent NOM surge. We expected NOM to be at 286,000 – instead it’s up to 518,000.

But here’s the thing: the current NOM up-spike is still way smaller than the NOM down-spike that happened during the pandemic (Figure 3). On the whole, we got 352,000 fewer people through net migration than we previously expected we’d have gotten by now."

What's their advice? That we should "probably worry less about it", which is what I've been saying for several months now: the data will self-correct, and before too long we're probably going to be begging for migrants to help fix our much larger policy mistakes, anyway.

2. Beware high frequency data

Australia's monthly consumer price index (CPI) was released on Wednesday, showing that inflation might prove to be a bit sticker than many were hoping. Especially our Treasurer, who did what only a politician can do by claiming that we shouldn't read too much into the data but that that the same data also show how good a job he's doing:

"As we've said many times the monthly inflation indicator can be volatile and is less reliable than the quarterly measure because it doesn't compare the same goods and services month to month... The ABS confirmed very clearly again today that inflation would be higher were it not for our cost-of-living policies."

Chalmers is referring to the government's Energy Bill Relief Fund, which "led to a 1.9% fall in Australia level Electricity prices in monthly terms".

But the thing is, electricity prices actually increased by 13.9%; households just haven't had to pay them – yet. That's because the CPI is only an imperfect measure of inflation that is easily distorted by government subsidies. The actual rate of inflation didn't change and when the subsidies run out, the affected components of the CPI will shoot right back up.

In fact, inflation is probably worse "because it [the subsidy] dulls the ability of prices to ration demand. If prices appear to have come down, people have less of an incentive to reduce their consumption of whatever good or service the government has meddled with".

But where Chalmers is correct is that the monthly inflation series can be a bit tricky to interpret because of how our stats bureau cobbles it together. Andrew Lilley wrote a nice little summary of some of the risks that can arise when trying to interpret the monthly series:

"The monthly CPI measures around half of goods monthly, a further 40% once per quarter, and around 10% once per year... This meant that in January, inflation (ex volatiles and travel) was flat on the month. This was broadly interpreted as a sign that inflation was crushed and the RBA would be cutting soon. But January has the equal lowest weight on goods updating quarterly and annually. Then in Feb, headline and all exclusion measures of inflation were annualising above target again, but that's just because of high inflation in education, which updates once per year."

Now, I fully expect the quarterly data to also show that inflation is being quite 'sticky'. It's hard not to come to that conclusion when services and non-tradables inflation looks to be settling at an annual rate above 4%, and many of the government's big-spending Budget items haven't kicked in yet.

Unfortunately, we won't have those data until the end of July. But in the meantime, beware anyone using the monthly data to make forecasts about interest rates.

3. The humans are safe... for now

A new paper from researchers at the University of Chicago made the headlines last week, because... well, why don't I just post one:

"GPT-4 is better than humans at financial forecasting, new study shows."

According to the study:

"Even without any narrative or industry-specific information, the LLM outperforms financial analysts in its ability to predict earnings changes. The LLM exhibits a relative advantage over human analysts in situations when the analysts tend to struggle."

Now that sounds like a big deal. A potentially very profitable deal, too. As the Business Insider article summarised, "the study found that applying GPT-4's financial acumen to trading strategies produced more profitable trading, with higher share ratios and alpha that ultimately beat the stock market".

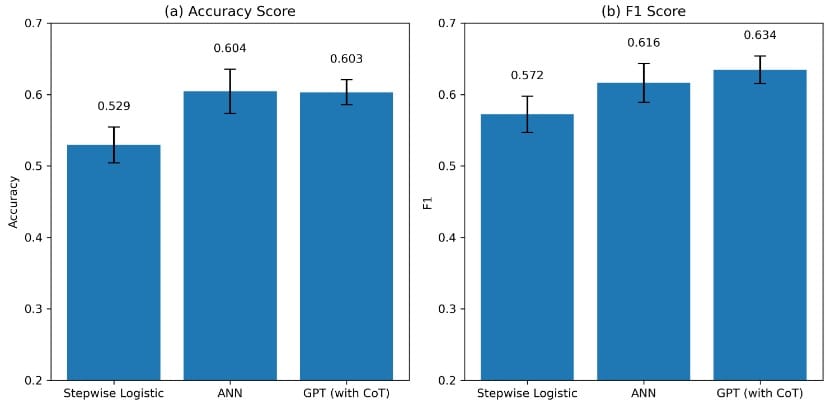

But there's a catch. The benchmarks used in the paper indicate that machines have been better than humans at this kind of stuff since at least 1989. Here is the relevant section, from page 40:

"This figure compares the prediction performance of GPT and quantitative models based on machine learning. Stepwise Logistic follows Ou and Penman (1989)'s structure with their 59 financial predictors. ANN is a three-layer artificial neural network model using the same set of variables as in Ou and Penman (1989). GPT (with CoT) provides the model with financial statement information and detailed chain-of-thought prompts. We report average accuracy (the percentage of correct predictions out of total predictions) for each method (left) and F1 score (right). We obtain bootstrapped standard errors by randomly sampling 1,000 observations 1,000 times and include 95% confidence intervals."

Here's the chart, which shows GPT having an accuracy below ANN and a F1 score only slightly higher:

If today's large language models are only slightly better than a model using a 3-layer neural network with 59 variables from 1989, then I don't think humans have all that much to worry about, at least in this space; it's not like quantitative analysts stopped working on these techniques 35 years ago! Given the knowledge problem, there are hard limits to how well humans or machines can perform in this space.

4. There is no pink tax

A couple of years ago, the World Economic Forum boldly proclaimed that:

"The pink tax has long imposed an economic burden on women around the world—especially since women continue to earn less than men."

Ok, sure, that sounds good – why should feminine products cost more? Down with the patriarchy and all that, right? Except... it turns out that the pink tax doesn't exist, once the products are properly differentiated:

"To solve this mystery, Moshary, Tuchman, and Vajravelu use 'a national data set of grocery, convenience, drugstore, and mass merchandiser sales'. They 'find that gender segmentation is ubiquitous, as more than 80% of products sold are gendered'. But crucially, they also find:

'…that segmentation involves product differentiation; there is little overlap in the formulations of men's and women's products within the same category… we demonstrate that this differentiation sustains large price differences for men's and women's products made by the same manufacturer.'

In short, the prices of men's and women's products differ because the products themselves differ. My wife could avoid paying the 'pink tax' on haircuts by asking for a number three on top and number two on the back and sides. She does not.

As the authors of the study caution, the "results call into question the need for and efficacy of recently proposed and enacted pink tax legislation, which mandates price parity for substantially similar gendered products".

Given that we're basically policy chameleons here in Australia, it wouldn't surprise me if someone, probably somewhere deep in the bowels of Canberra, has already drafted up a plan to combat this non-existent problem.

5. I can think of a few better uses

Ah, "soft diplomacy". Much like national security, is there any use of taxpayer's dollars you can't justify by promising something completely unquantifiable, with no consideration for the trade-offs? Here's the latest entry, a $600 million gift for a new rugby league team in Papua New Guinea (PNG):

For reference, that's $64 per Australian household, the majority of which do not care for rugby league. It's also $600 million being spent in a country where 65.6% of the population live in poverty (incomes below $US3.20/day), 82.6% don't have electricity, and 69.2% have limited drinking water.

It's also one of the most unequal countries in the world outside of sub-Saharan Africa, with the majority of the population living in rural areas with no reasonable prospect of attending a rugby league match.

So thank you, Albo, for using our tax dollars to subsidise and validate PNG's elites, many of whom I'm sure have played their part in impoverishing their people through its extractive institutions, but who no doubt live in a nice part of Port Moresby close to the stadium and will fancy a bit of footy on Saturday's. 👏

6. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

The return of the Tariff Man – Biden's new China tariffs are driven by politics, not economics or national security. But protectionism tends to beget more protectionism, risking trade wars that could cause significant damage to the global economy.

Australia's demographic dilemma – Australia's migration slowdown will ease housing issues but exacerbate its ageing population and fiscal problems, requiring unpopular entitlement reform and improved fertility rates to sustainably fund old-age benefits.

Have a great weekend.

Member discussion