Friday Fodder (27/24)

1. The misplaced backlash against neoliberalism

Blogger Matt Yglesias (of the "centre-left"), after acknowledging that the word neoliberalism is often misused such that "nobody is 100 percent sure what anybody means", noted that most criticisms of it are quite "sloppy":

"[T]he backlash against neoliberalism has, I think, mostly served in practice as a way to tell people that it's okay to do sloppy economic analysis or say things that aren't true. One of my most contrarian views is that accurate policy analysis is badly underrated, in part, because most organisations don't actually have the capacity to do it. So excuses for sloppy thinking and denying the existence of tradeoffs tend to be popular."

Regular readers will recall a sloppy take-down of neoliberalism I wrote about here. But Yglesias goes further, questioning whether neoliberalism – which its critics define as "the free-market, anti-government, growth-at-all-costs approach to economic and social policy" – ever really got going:

"The idea that for the last 50 years we've been on a manic quest for growth is confused. In reality, we've seen during that time period increasing levels of political influence wielded by people (mainly environmentalists and NIMBYs) who are sceptical of economic growth.

...

[M]ore broadly, 'everyone knows' that the neoliberal era has been an era of deregulation, even though it's also pretty clearly true that the overall scope of regulation is larger in 2024 than it was in 1974."

What did happen was governments stopped meddling with wages and prices, "the prestige and policymaking clout of economists went up a lot", unions lost influence (clearly not the CFMEU...), and there was more of a focus on competition and efficiency.

But we're about to see the election of Donald Trump versus Joe Biden, assuming the latter survives this week, let alone to November. Both men have reversed the "process of deferring to mainstream economics in the policymaking sphere, but also with a lot of talk about new paradigms and threats to impose new doctrines in the antitrust sphere or revive price regulation".

This week, Biden proposed implementing national rent controls on "corporate landlords" that will only worsen housing affordability, while Trump wants to tariff all imports, which would have disastrous effects for US industry given how reliant US firms (including its exporters) are on imported intermediate goods.

So, no matter who wins in November, the assault on neoliberalism – or what remains of it, anyway – looks set to continue for another four years.

2. In a sticky spot

That's the title of the IMF's latest World Economic Outlook, in which it cautioned that inflation might hang around for a while (I gave a similar warning back in April):

"[T]he momentum on global disinflation is slowing, signalling bumps along the path. This reflects different sectoral dynamics: the persistence of higher-than-average inflation in services prices, tempered to some extent by stronger disinflation in the prices of goods. Nominal wage growth remains brisk, above price inflation in some countries, partly reflecting the outcome of wage negotiations earlier this year and short-term inflation expectations that remain above target."

Given this is the shorter version Australia didn't get a mention, although the IMF did downgrade our 2024 real GDP growth estimate by 0.1 percentage points to just 1.4%, which is in the bottom half of the countries surveyed.

As for the risks, well, look no further than Trump versus Biden and the inevitable global retaliation:

"Trade tariffs, alongside a scaling up of industrial policies worldwide, can generate damaging cross‐border spillovers, as well as trigger retaliation, resulting in a costly race to the bottom. By contrast, policies that promote multilateralism and a faster implementation of macrostructural reforms could boost supply gains, productivity, and growth, with positive spillovers worldwide."

I'm glad the IMF is still writing about what we should be doing. But at least for the next few years, the world – including Australia – looks set to move further in the other direction.

3. Hong Kong's expat exodus

The Washington Post's Keith Richburg recently penned an interesting opinion piece on Hong Kong, specifically about the departure of expats and how the former bastion of capitalism "is becoming just another mainland city":

"Much of this exodus was spurred by the covid-19 pandemic; Hong Kong's draconian quarantine rules curtailed overseas flights, cancelled school and strictly enforced mask-wearing. Then came Beijing's national security law, which stifled free speech, leading to the closure of media outlets and forcing scores of civil society groups to shut down. This year, Hong Kong authorities, newly obsessed with the tinfoil-hat theory of the city being infiltrated and influenced by 'foreign forces,' doubled down on repression by passing their own local security law."

As a former resident of Hong Kong, let me tell you that this was always going to be the outcome following the handover and agreement to "one country, two systems". The pandemic just accelerated the transition.

It's not disastrous: China still needs Hong Kong, in the sense that it needs as many relatively free economic zones as it can possibly get, especially a financial hub well-situated on the South China Sea. And mainland Chinese cities are still destinations for expats, although even their appeal was waning prior to the pandemic, perhaps as China's economy slowed (limiting opportunities), domestic talent caught up, and of course Xi Jinping took the reins.

As for Hong Kong, local officials are responding to the 'brain drain' by importing mainlanders:

"In their view, the troublesome foreigners can be easily replaced by patriotic mainland Chinese, who can do the same jobs better. Various new government schemes to attract 'global talent' brought in more than 100,000 new arrivals last year — 90 percent of them from mainland China. Mandarin is slowly replacing English as the city's second language, after Cantonese."

Hong Kong is already just another mainland city.

4. Why are there so many male managers?

Gender expert Alice Evans recently broke down a new paper about the gender "leadership gap". The conclusion – based on a massive German dataset – is that "junior men are more likely [than women] to apply for promotions". It turns out that the effect:

- holds even controlling for various other factors; and

- disappears once women apply for, or currently hold, a leadership position.

Evans discusses many reasons why junior women might not be applying for these leadership positions, ruling out discrimination, existing male dominance, expected rejection, confidence, care responsibilities, and childcare. The difference appears to be in the desire to lead a team, perhaps because women with no leadership experience overestimate how difficult it will be:

"Male and female team leaders were asked about their roles, e.g. team size and frequency of conflict. Their answers are similar.

When lower-level female employees were these exact same questions, they tended to envisage larger teams and more frequent conflicts. In fact, these are misperceptions.

Lower-level women's perceptions of team leadership are more negative and inaccurate."

Evans goes on to discuss possible reasons why women might think this, and ways to test it more broadly. All very interesting stuff, including the comments. If true, it might mean that one of the better ways to increase the share of women in management would be to start exposing them to leadership earlier in their careers.

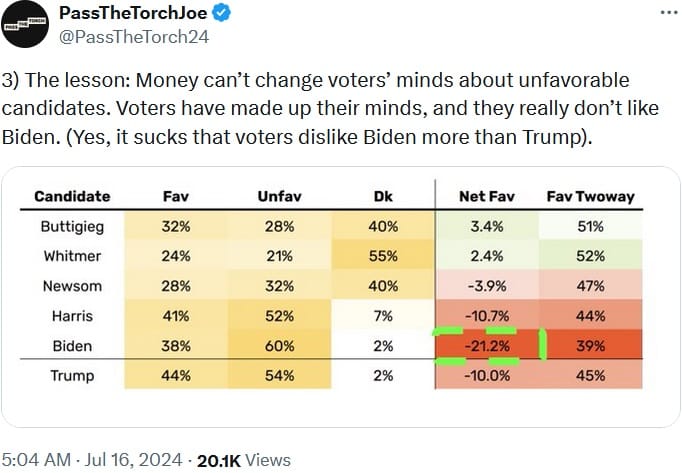

5. Biden has no chance

President Joe Biden, currently on a leave of absence after coming down with Covid, "has no chance, and all replacements would do much better":

That's from a long thread by anonymous X account "PassTheTorchJoe", which is supposedly "A grassroots campaign to call on President Biden to step aside as the nominee for President and support the candidate best able to beat Trump".

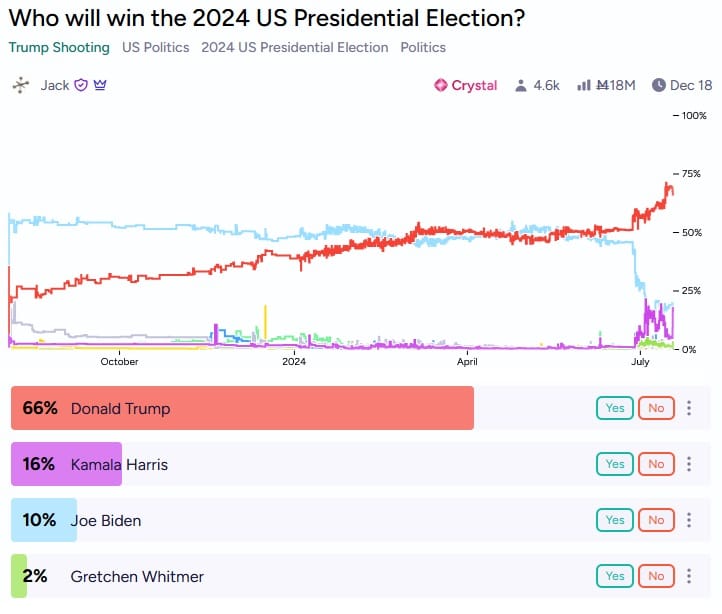

Its logic would appear to be supported by betting markets, which now have Kamala Harris well above Joe Biden (but both trail Trump by a considerable margin).

It will be interesting to see if Joe Biden, who lusted over Presidential power for many decades before eventually claiming it at the age of 78, is capable of taking one for the team and stepping down from the 2024 ballot, even now that the entire Democratic establishment is against him and polls give him no chance of beating Trump.

6. It's not too late for nuclear

For all the valid arguments against nuclear, saying it's too late is not one of them. In fact, it's a classic take on the sunk cost fallacy: because we've invested so much in renewables, it would be silly to pivot to nuclear now!

Anyway, it looks like Italy will be the latest country to jump on the nuclear bandwagon, and "is planning to reintroduce nuclear energy 35 years after Italy shut down its last atomic plant", with the aim of nuclear providing 11% of its total energy consumption by 2050:

"'To have a guarantee of continuity on clean energy, we must insert a quota of nuclear energy', energy security minister Gilberto Pichetto Fratin told the Financial Times.

Renewable technologies such as solar and wind power 'cannot provide the security that we need,' he argued, reflecting his government's scepticism towards these technologies."

Italy's last plant closed in 1990 following a referendum triggered by the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in the Soviet Union. But perceptions have changed, and people might be becoming more concerned about the country's reliance on China for renewables and their unpleasant impact on tourism than on a nuclear disaster:

"Young people are more aware, the elderly less so. They are of the Chernobyl generation and when they hear talk of nuclear power... they automatically say no.

It is clear that the development of solar is strongly linked to imports from China... a country that has a very government-controlled enterprise system, which can be a political, as well as commercial tool."

Nuclear really is the perfect, carbon-free substitute for coal. As more countries get involved and start to regulate it properly (a key reason why it's so expensive in many places today), I fully expect costs to come down.

7. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

A sensible nuclear policy is in the nation's interest – Australia's nuclear energy debate highlights the need for a sensible, economically sound approach to carbon reduction that considers all options, rather than politically-driven policies that may prove inefficient and costly.

Migrants aren't causing inflation – Inflation is caused by fiscal and monetary policy, not by migrants or other supply shocks, which can only temporarily affect measured inflation by altering relative prices in the economy.

Have a great weekend.

Member discussion