Good intentions aren't enough

Australia's June quarter CPI data are due to be released today and will go some way to informing the RBA's next cash rate decision on 6 August. My view is that rates should be kept on hold no matter what the inflation figures show, but these days you never really know. The RBA has a deep credibility problem following its pandemic mistakes, so if it doesn't look like it's making progress, then Governor Bullock might be tempted into a hike if for no other reason than to avoid further scrutiny.

So, here's hoping for a quarterly rise under 1%!

But today I want to discuss policy. Specifically, the NSW government's decision to proceed with "no fault" evictions legislation:

"From next year, landlords will have to meet one of several 'commonsense and reasonable' thresholds for eviction, which include the sale of the property or if the tenant causes damage.

There will be an obligation on owners to provide evidence when issuing an eviction notice, with penalties for 'non-genuine' reasons.

The reform will apply to everyone who is covered by the Residential Tenancies Act."

To be clear, such legislation already exists in most other jurisdictions; as far as I'm aware, only WA doesn't have similar tenant protections in place.

But banning no-fault evictions is more of a feel-good policy than anything that will meaningfully affect the rental market. Being a tenant gets a little bit better, so demand for rentals will increase. But landlords will raise their risk premium because it's slightly more difficult to evict tenants, reducing the supply of rental properties over time. And as we all know, when demand goes up and supply goes down, equilibrium rents (prices) will increase.

In fact, a recent paper by Columbia's Boaz Abramson found exactly that effect:

"I find that stronger eviction protections exacerbate housing insecurity and lower welfare. The key driver of this result is the persistent nature of risk underlying rent delinquencies."

So, what does work? Abramson found that giving renters means-tested cash is quite effective at improving welfare in the short run, and that the gains of doing so are greater than the cost to taxpayers:

"Rental assistance, in contrast, reduces evictions and homelessness and improves welfare because it lowers the likelihood that renters default ex-ante."

The problem, of course, is that governments have to spend money to provide rental assistance, whereas the direct effect of banning no-fault evictions is virtually costless to the government (although it will eventually raise fiscal costs indirectly, e.g. due to higher homelessness).

The short run effects will be negligible, perhaps even positive, but the negative indirect effects will take a longer time to be felt. Banning "no-fault" evictions also sounds good to those who aren't familiar with economics, i.e. the vast majority of the population, including most politicians (even if they mean well), which is one why such policies are so popular.

But if the long-term goal is to make housing in Sydney more affordable, then good intentions aren't enough.

Beyond good intentions

I was hopeful for the Minns NSW government. Indeed, I've praised the government's approach to housing twice: first in February, then again in March. But as so often happens, interest groups get themselves organised and start throwing copious amounts of sand into the gears of would-be reformers. The reforms then get watered down, or scrapped entirely.

Take the state's Transport Oriented Development program. Announced in December 2023, the plan was to apply "accelerated rezoning" to a bunch of well-located suburbs within 1,200m of Metro and rail stations, followed by a "snap rezone" of dozens of suburbs within 400m of Metro or suburban rail stations. It also committed a bunch of cash for "community infrastructure" to help support the expected increase in density.

But only two months later, the a bipartisan group of politicians launched a Parliamentary inquiry into the development of the program. That inquiry won't even table a report until 27 September, but considerable local government opposition has already led the government to scale down its original plan:

"The state government will water down its key housing density policy with significant concessions to local councils that have alarmed housing advocates ahead of the release of a new five-year plan for Sydney and surrounds.

A 'policy refinement paper' seen by the Herald reveals several types of land will be excluded from the imminent low- and mid-rise housing reforms, which aim to increase the supply of duplexes, terraces and small apartment buildings within 800 metres of train stations and town centres.

...

It is not the government's first compromise on housing policy. As the Herald also revealed, it granted several councils more time – up to 15 months – to work on local housing plans rather than being captured by the TOD program, slated to apply in 37 suburbs with train stations."

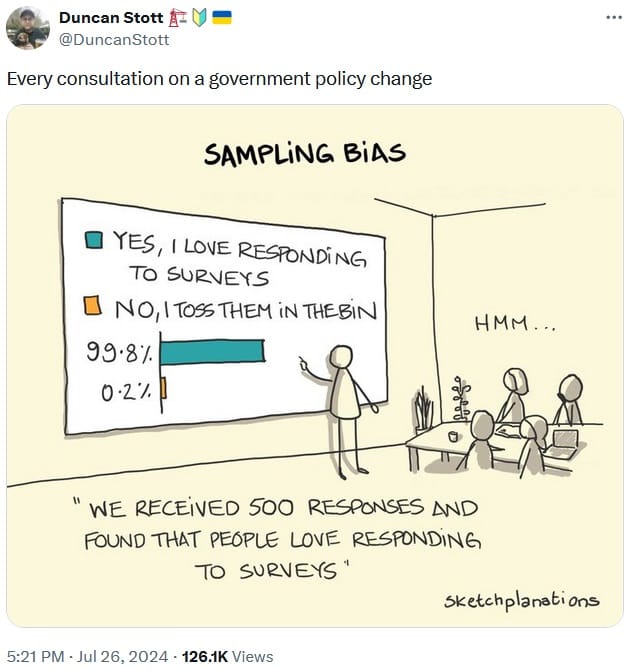

I understand that "community consultation" is important, but all too often it's simply a way for home-owners, who lucked out by being born when well-located land was relatively plentiful and affordable, to pull the ladder up behind them.

Community consultation also suffers from what's known as survivorship bias. That is, the people most likely to participate such "consultation" processes are not representative of the community as a whole:

"We match individuals to a voter file to investigate local political participation in housing and development policy. We find that individuals who are older, male, longtime residents, voters in local elections, and homeowners are significantly more likely to participate in these meetings. These individuals overwhelmingly (and to a much greater degree than the general public) oppose new housing construction."

Or, in meme form:

One reason why we can't build enough of anything – housing, renewables, transport, you name it – is because we overweight the value of consultation in the decision-making process. A minority of residents then obstruct development, because the majority is just too busy and has too small of an individual stake to get involved.

In my view, there are two ways governments can address that: top-down coercion, as I've proposed before; or, by trying an Elinor Ostom-inspired approach of giving local communities more skin in the game, for example through the ability to claim a share of the profits from new developments. Without such incentives, and where a top-down approach fails (say, from political pressure), not enough housing will be built.

The problem with not giving local communities a 'cut' is that the existing residents do suffer legitimate costs and should perhaps be compensated for that loss. As Harvard's Ed Glaeser has argued, "fiscal resources will be needed to convince local residents to bear the costs arising from new development":

"On pure efficiency grounds, one could argue that the federal government should provide such resources, but from a political economy perspective, the median taxpayer in the nation effectively transferring resources to much wealthier residents of metropolitan areas like San Francisco seems challenging to say the least."

Yeah, transferring tax dollars to residents of Mosman would be highly regressive and probably wouldn't go down all that well with the rest of NSW. But if they had a say in – and stood to profit from – new developments, then maybe enough of them would reconsider their opposition, or start participating in the "consultation" process to balance out the older, male, longtime homeowning residents.

But back to the rental crisis.

We need to build, build, build

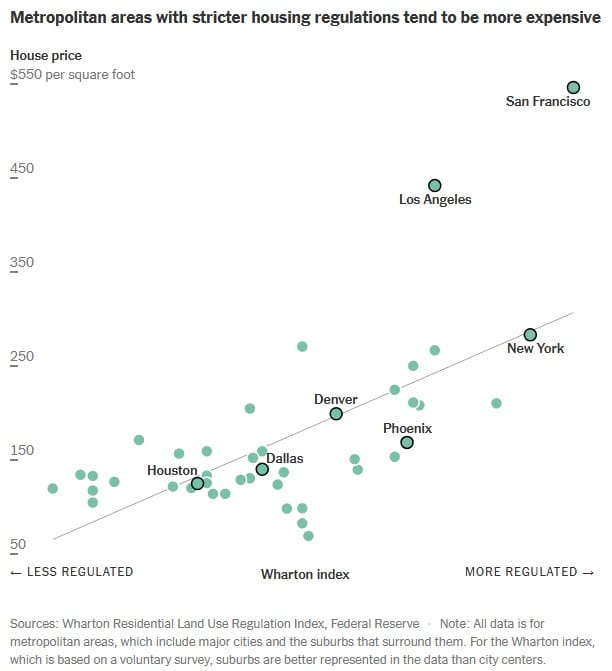

There is no question that best way to improve housing and rental affordability in the long run is by increasing supply. There's a solid link between regulation that restricts supply and housing prices, which flows directly to rental prices:

Unfortunately, NSW isn't doing very well on the housing front, with just 1,597 private houses approved in June:

"Last year about 48,000 homes were completed in NSW, well short of the state's target of 75,000 homes a year for the next five years to meet the National Housing Accord targets."

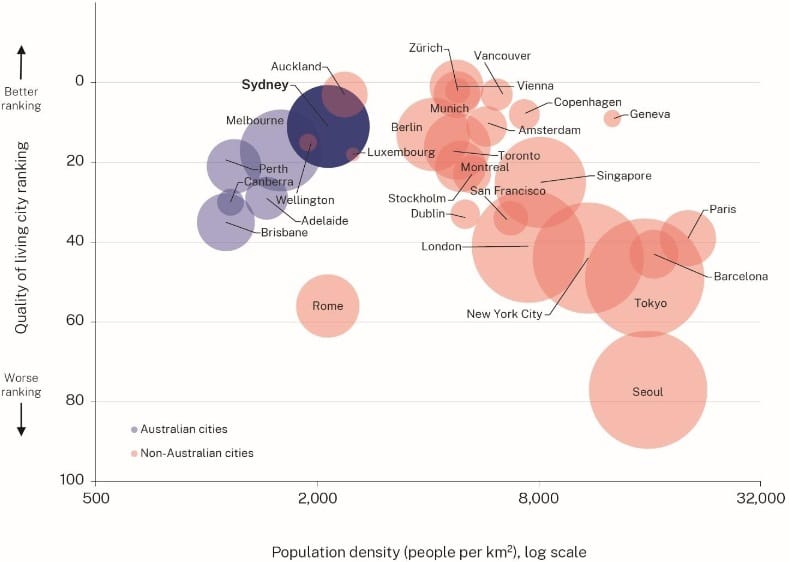

Not only is NSW behind on its building targets, but it's also not building housing where people most want to live. According to the NSW Productivity Commission, fewer than 20% of new dwellings were built within 10 kilometres of Sydney's CBD between 2016 and 2021. We could add a lot more well-located housing and still be on the 'low' end of the global density scale, without compromising quality of living:

And as much as I like to point the finger at obstructionist local governments, that 'feature' of our cities is mostly the fault of state government master planning:

"These plans prioritised growth outside of the existing, highly productive economic centres by setting jobs and housing targets across Western Sydney, for example, rather than enabling more housing near existing jobs (or otherwise where demand and feasibility was greatest)."

So, it's pretty clear that the NSW can do plenty to get its own house in order before messing with the rental market. Again, here's the NSW Productivity Commission with the final word:

"Given Sydney's struggle both to deliver enough housing, and to deliver it in the areas people most want to live, it is in some sense unsurprising that we are in the current affordability crisis. To address the crisis, dwelling targets should be adjusted to better match existing demand-supply imbalances. This would require increases in dwelling targets in inner city areas relative to the middle- and outer-rings of Greater Sydney."

Most policies are ineffective

Moving to the federal level, the Albanese government's approach to the housing crisis has been... underwhelming. For example, Help to Buy will only add 40,000 dwellings at a cost of $7.6 billion. That's not going to do much into a dwelling stock of 11 million, and almost certainly doesn't justify its considerable cost.

Then there's the Housing Accord's target of "1.2 million new, well-located homes" by 2029, which only started this month and already looks unachievable. After a post-pandemic surge, new housing commencements have fallen back down to below the long-run average of around 26,500:

Add to that high interest rates, elevated construction costs, needing to navigate the existing planning system, pervasive NIMBY attitudes, and the target of 60,000 new homes every quarter for five years is basically impossible.

No wonder Anthony Albanese just 'reshuffled' his Cabinet, replacing Housing Minister Julie Collins with Clare O'Neil, in part because the latter "is a great communicator"!

But there is good news. ABS long-run projections out to 2046 imply growth of between 1.1% and 1.3% annually, which translates to housing demand of around 135-160,000 dwellings each year (net of demolitions), i.e. well below the Accord's target. So, even if the government fails at achieving its target of 240,000 homes a year, the housing market may well still move towards surplus.

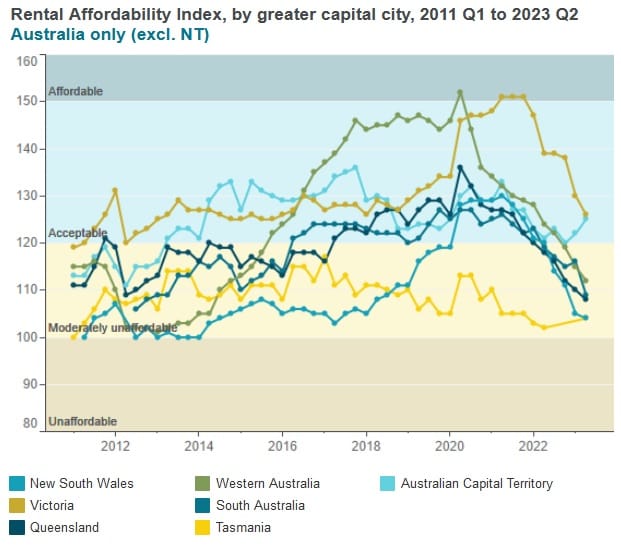

In addition, indications are that the rental crisis will be temporary. Australia's capital city rental affordability index has certainly deteriorated over the past few years, but that just means that most cities are now back to around where they were a decade ago:

We weren't calling it a "rental crisis" back then, because the variation between years wasn't all that big. What has shocked people is the rate of change – they had grown accustomed to paying less of their disposable incomes on rent than they were a decade ago.

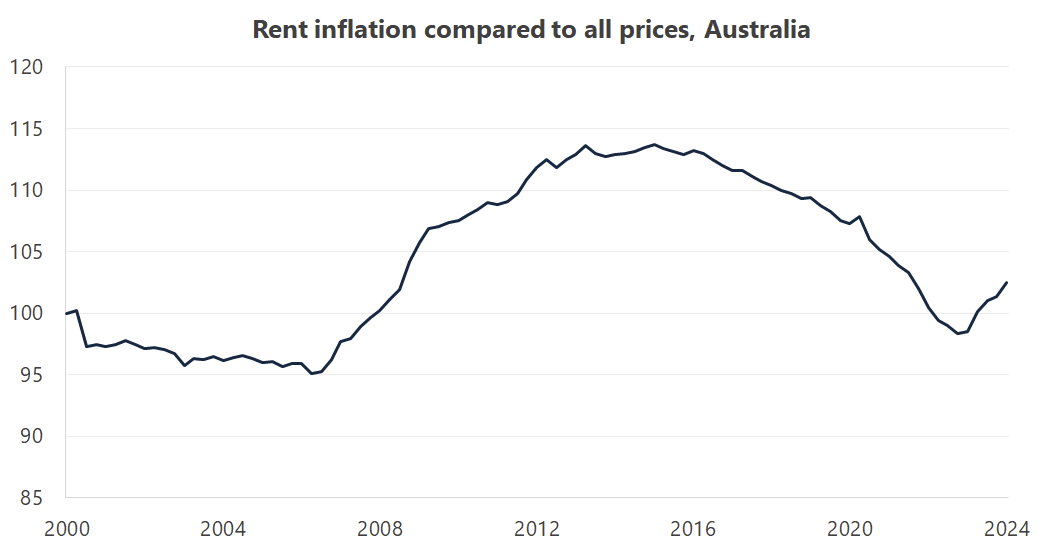

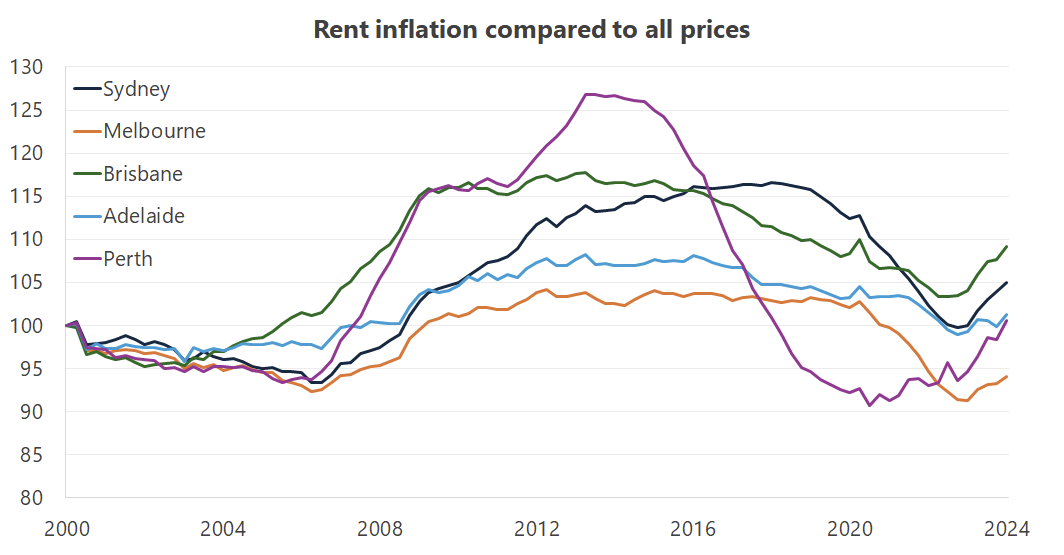

Another way of measuring rental affordability is as a share of overall prices. The RBA targets 2-3% annual inflation, so you would expect if housing supply and demand were balanced then rental inflation would match overall inflation (i.e. be flat at 100):

It's clear that the rental market is part of a property cycle: we have periods where prices rise and fall more slowly than overall prices, and periods where they rise and fall faster – sometimes much faster, as was the case for Perth during and following its two mining booms:

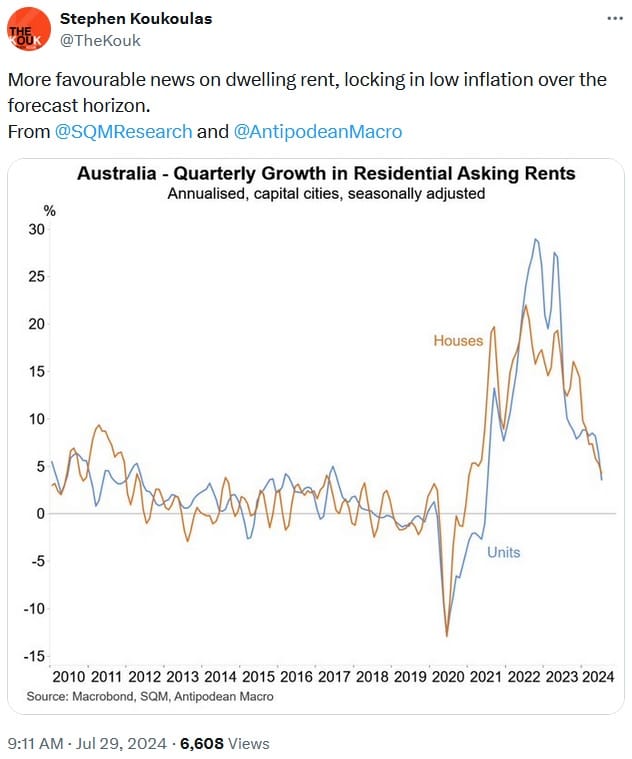

Basically, we're in a rental crisis only if we look at the last few years. Over a longer period of time, the relationship between rental prices and overall prices is only a bit above where it was a decade ago. And the rate of growth in asking rents, some of which will eventually flow into average rents, are already cooling down quite rapidly:

Don't get me wrong: some people have seen their rent shoot up, and that sucks. Some are legitimately in hardship, and the government should look to provide temporary relief to those households.

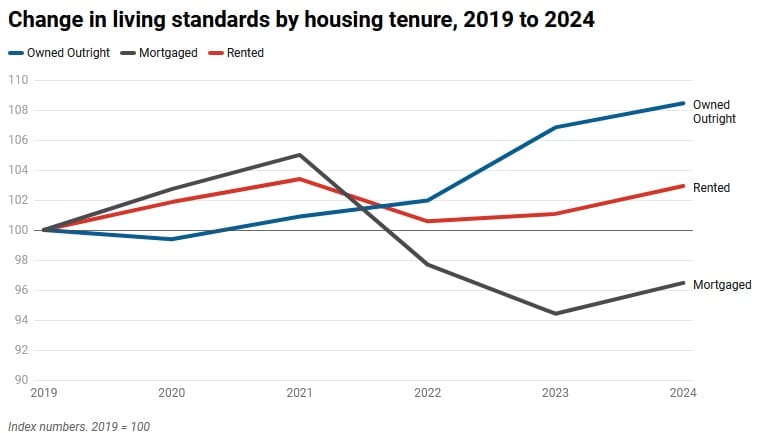

But for most renters, the rental crisis has been vastly overblown. As of January 2024, the average renter is actually financially better off than they were in January 2019 because their incomes (including government transfers) rose faster than rents:

So I predict that by the time government policies – other than direct programs such as Commonwealth Rent Assistance – actually do anything meaningful to housing supply, the rental crisis will already be over.

There's still plenty to do

Australia still has a housing affordability problem, which requires a policy response with a long-term perspective. But politicians tend to be concerned with short run costs and benefits (i.e., their re-election), so when the rental crisis fades from the front pages, so too will their attention.

So while we have their attention, it's important to get meaningful reform going. A housing target isn't good enough; what's needed is actual reform, or in a decade we'll be the only country where young people cannot afford a home. Many advanced economies are already making headway, for example:

- The new centre-left British Labour government has promised significant reforms to the country's land use planning system, and declared "war" on NIMBYs.

- In New Zealand, the new conservative government wants to "flood" the property market with new houses by defanging local governments.

- Pierre Poilievre, who looks likely to become Canada's next Prime Minister, looks keen to "bring a pretty sharp stick to the cities and their housing activity".

Such reforms have been shown to improve affordability in the long run, and they don't even come at the expense of house prices, at least initially:

"Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy of the University of Auckland has found that rents, adjusted for property quality and size, are 28% lower than they would be had they continued to track a 'synthetic Auckland', based on a mixture of smaller Kiwi cities that resembled Auckland before the reforms.

House prices have risen just as fast as in the rest of New Zealand. Mr Greenaway-McGrevy attributes this to the fact that upzoning has increased land values: pre-existing smaller homes now sell for more since they are bundled with the option to build larger units. Once the market adjusts, prices may begin to rise more slowly or even fall."

To wrap things up, the best way to alleviate a short-run rental crisis is by increasing targeted rent assistance, which in Australia can be done through the Commonwealth's Rent Assistance program.

But in the long-run, we have to unclog the planning system – including removing outdated mandates, such as parking requirements that can add up to $100,000 to the price of a dwelling – so that supply can respond to demand and we can build more houses when they're needed. Doing so will reduce volatility in the housing cycle, lowering the chance that we end up in another housing crisis in the future. And without perpetual crises, the risk that politicians attempt something much stupider than banning no-cause evictions, like imposing rent controls, also falls.

Member discussion