How big is too big?

Last week Australian entrepreneur and founder of his namesake, Dick Smith, debated the Centre for Independent Studies' Emilie Dye on immigration. Smith took the anti-immigration viewpoint and made it very clear that he vociferously opposes what one might call a 'Big Australia' [emphasis mine]:

"The figures are actually worse at the present growth rate, from the huge immigration, we're going to end up at 100 million people in Australia when our grandkids will still be alive at the end of this century.

No one believes 100 million is sensible for an arid country like Australia, the figure should be about 75,000 a year. I am pro-immigration; I think it's really fantastic. But 75,000 a year will round off our population at about 30 million, and that sounds a pretty sensible number to me. Having more people normally means you're spreading the wealth and that with more people everyone gets less."

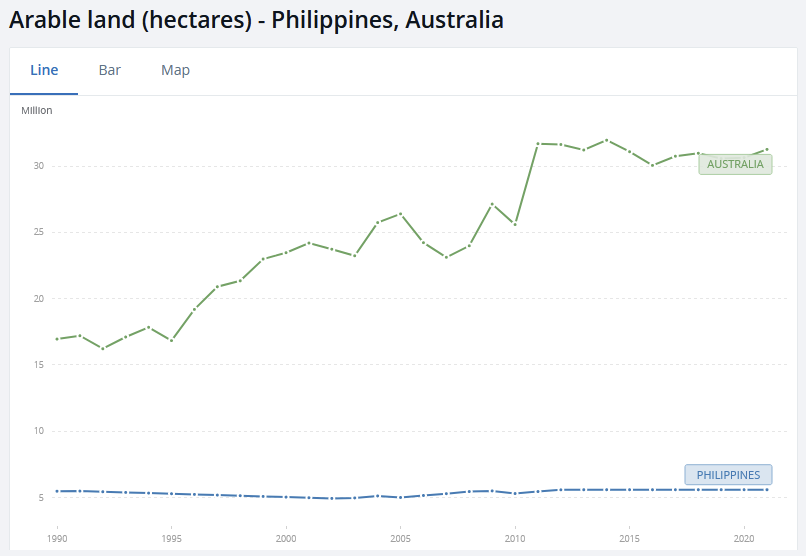

Oh boy. For context, there are 16 countries out there that already have a population over 100 million. Only four of those – China, the US and Russia – have more land than Australia. I get that not all of Australia is what one might consider desirable land, but we still have the 10th most arable land in the world. Of those top 10, only Canada, Ukraine, Argentina and Australia don't have more than 100 million people living in them.

In other words, ignoring all the costs and benefits of population and focusing purely on assertion that an "arid country like Australia" doesn't have enough space to accommodate a bigger population, Smith's claim falls flat: we could comfortably fit a lot more people.

We probably wouldn't even need more cities, either. If Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide, with their combined average density of around 400/km2, increased that to just 12.5% of Seoul, 10% of Paris, or 5% of Manila, they would have accommodated 100 million people.

Our issue isn't a lack of space, or being too arid – with the exception of Adelaide, all of our major cities get more annual rainfall than Paris (with more people technology such as desalination becomes more economical, anyway) – we just don't use what we have all that well.

The good and the bad of population growth

I'm currently in the Philippines, so it'll make for a decent case study. This is a country with a population of around 118 million, a number that has grown from just 10 million only a century ago, back when Australia had 5.5 million people. Over the ensuing hundred years, Australia grew by around 385% to the Philippines' 1,080%, despite the Philippines being a relatively small archipelago and a lot less suitable to growing food than Australia. From not quite double Australia's population a century ago, the Philippines is now home to nearly five times as many people as we do.

That's not to say population is a good thing in and of itself; the Philippines is hardly a wealthy nation, and arguably grew too quickly for its underdeveloped institutions to handle when compared to Australia. For example, the Philippines ranks poorly in terms of corruption (115/180 countries) and ease of doing business (95/190 countries), while Australia ranks in the top 15 globally for both.

What I'm saying is that when your institutions are good enough to encourage productive (e.g., investment) rather than zero-sum (e.g., corruption) behaviour, people are the ultimate resource: they innovate, solve problems and in the long run, make us all better off, provided they're given the freedom to do so:

"Adding more people causes problems. But people are also the means to solve these problems. The main fuel to speed the world's progress is our stock of knowledge; the brakes are our lack of imagination and unsound social regulations of these activities. The ultimate resource is people—especially skilled, spirited, and hopeful young people endowed with liberty—who will exert their wills and imaginations for their own benefits, and so inevitably they will benefit the rest of us as well."

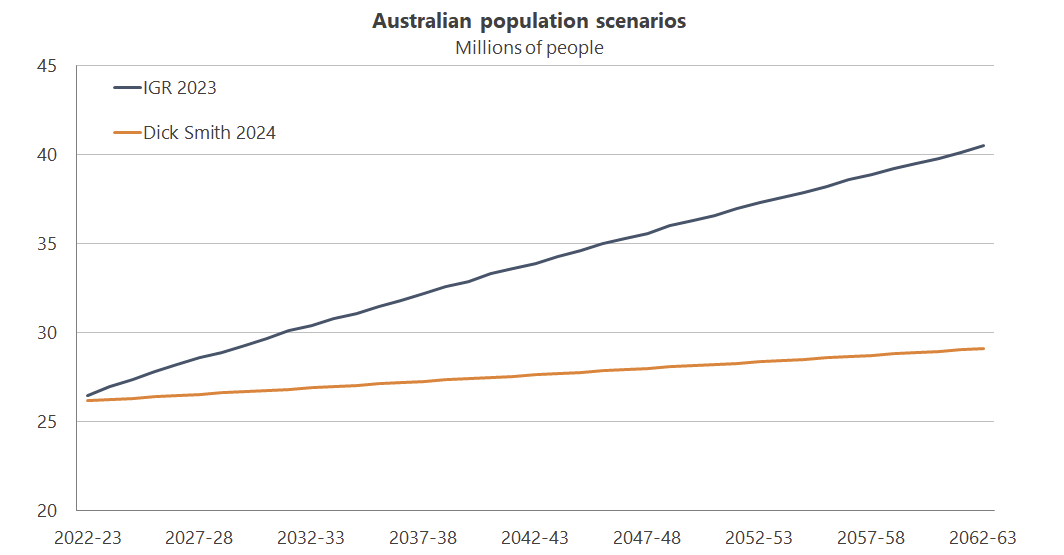

Dick Smith's arbitrary limit of 75,000 immigrants would see Australia's population grow by less than 0.3% each year out to 2063, with the rate of growth declining each year due to falling fertility. Each generation of Australians would get smaller, and the share of Australians aged over 65 would being to rise rapidly. A declining number of young, energetic people working in this country, combined with a growing number of aged dependents, would see the country's living standards very quickly fall behind places where immigrants were still welcome. Smith might not be around when that happens, but his grandkids would certainly be worse off in that world.

The pie isn't fixed

During the debate, Emilie did a good job at pushing back against Smith's other claim that with more people "everyone gets less", pointing out that there's not "a finite number of resources" to be spread around – a common mistake we economists call the "lump of labour fallacy". It goes something like this:

"Imagine the economy is a pie. According to the lump of labor fallacy, the size of this pie is fixed. For one person to get a bigger piece, the other pieces (by definition) would need to get smaller. Economists, however, often point out that the economy is not fixed—it is dynamic and expands over time. The individual pieces of the pie can get bigger together.

Economies grow as productive resources (such as labor or capital resources) are added: That is, more inputs (resources) increase the output produced. Economies also grow when productivity increases: That is, they grow when output per input increases. For example, the same automation that might displace workers in a particular industry might also contribute to rising productivity in that industry and thus the economy overall. Also, as workers acquire education and training, they contribute to a more productive economy. So, our second lesson is that the economy does not have a fixed size—it grows. And a growing economy increases the likelihood that job opportunities and standards of living will increase over time."

There will of course be losers from higher immigration or birth rates – and there's a legitimate role for government to assist those individuals – but in aggregate, the country is much better off by having more people. According to Treasury, immigration has played a key role in Australia's success:

"Due to changes in Australia's immigration arrangements over time, migrants to Australia have increasingly been young and skilled. These migrants have softened the impact of Australia's ageing population, boosted labour force participation, and increased the diversity of Australia's workforce. The economic and fiscal benefits that migrants have brought to Australia have undoubtedly played a part in Australia's 26 years of uninterrupted growth."

None of that means that there aren't costs, just that the benefits more than offset them.

Why house prices are high

The final claim I'd like to take issue with is Smith's assertion that population growth is the "prime reason" for high housing prices in Australia:

"The prime reason for high housing prices is the huge population increase. We're not blaming anyone, it's just a fact that if in a marketplace you bring in an incredible amount of people wanting to purchase houses, you're going to put the price up, and that's what's happened. I've benefited from growth, without any doubt, but what I'm concerned about is my grandchildren."

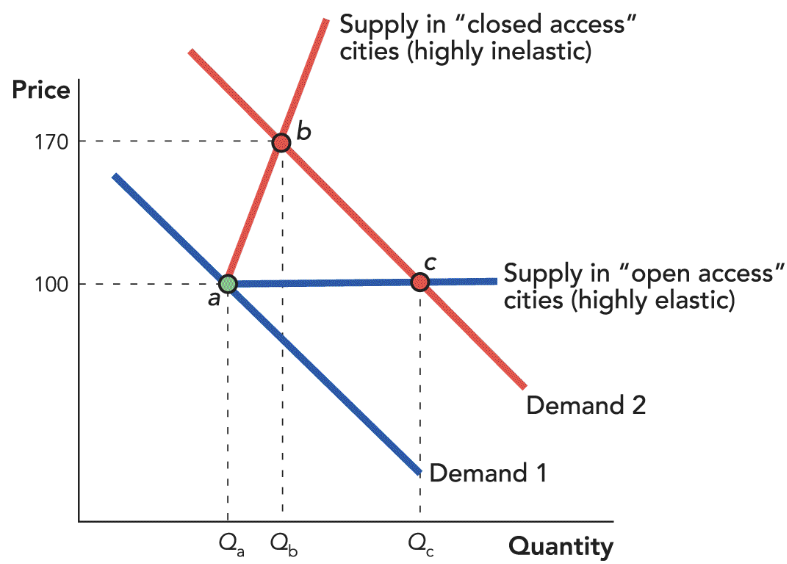

Smith is correct that adding more people, all else equal, will increase house prices. But when looking at any market you have to consider demand and supply. It's quite literally Econ 101. We even have nice, simple charts for what it looks like when demand for housing increases, say due to population growth, but the supply of housing is relatively inelastic (i.e., unresponsive to higher prices).

"When demand increases in a closed access city [where it's difficult to build], the equilibrium moves from point a to point b. Notice that prices increase a lot and the quantity of housing increases only slightly. In comparison when demand increases in an open access city, the equilibrium moves from point a to point c where the quantity of housing increases a lot and prices increase only slightly."

It's also important to know what type of immigrant they are. For example, if they're mostly young labourers and tradies, they will decrease the cost of construction and increase the number of structures built, more than offsetting their own demand for housing.

Smith can blame immigration for high house prices until the cows come home, but they're just a single – and by no means the largest – factor affecting prices. To be sure, there are good and bad ways to run an immigration program. But so far Australia's approach has proven to be one of the better ones.

If Smith truly cared about his grandkids' prospects of home ownership, he needs to focus on the true cause of high prices, one that is entirely self-inflicted. For decades, governments have repeatedly stimulated demand with things like first home-buyer grants, while simultaneously restricting supply with stringent zoning rules, thereby raising prices even more. Similarly, our transport infrastructure problems stem from politicians not knowing how to rein in their ambitions of grandeur, with poor governance leading to inefficiencies where 30% of the potential gains to public infrastructure investment could remain unrealised.

Fix those problems, and you fix housing. Immigrants are just the convenient scapegoats for those who, like Smith, mean well but don't understand the what's actually going on.

Member discussion