How not to do migration

Australia has a long and successful history of immigration. Migrants contribute economically, help fill labour shortages, improve the country’s demographics and provide important cultural diversity. But as countries like Sweden have learned, migration can also present significant challenges.

For example, last week independent economist Chris Richardson claimed that “we’re doing truly generational damage in housing”, in part because:

“[A]lthough a strong migration intake can make great sense, Australia’s mounting failures on all the other policies that need to accompany that [e.g., housing] mean we’re in a hole… [so] we’ll also need to wind back migration – including student numbers – for a time.”

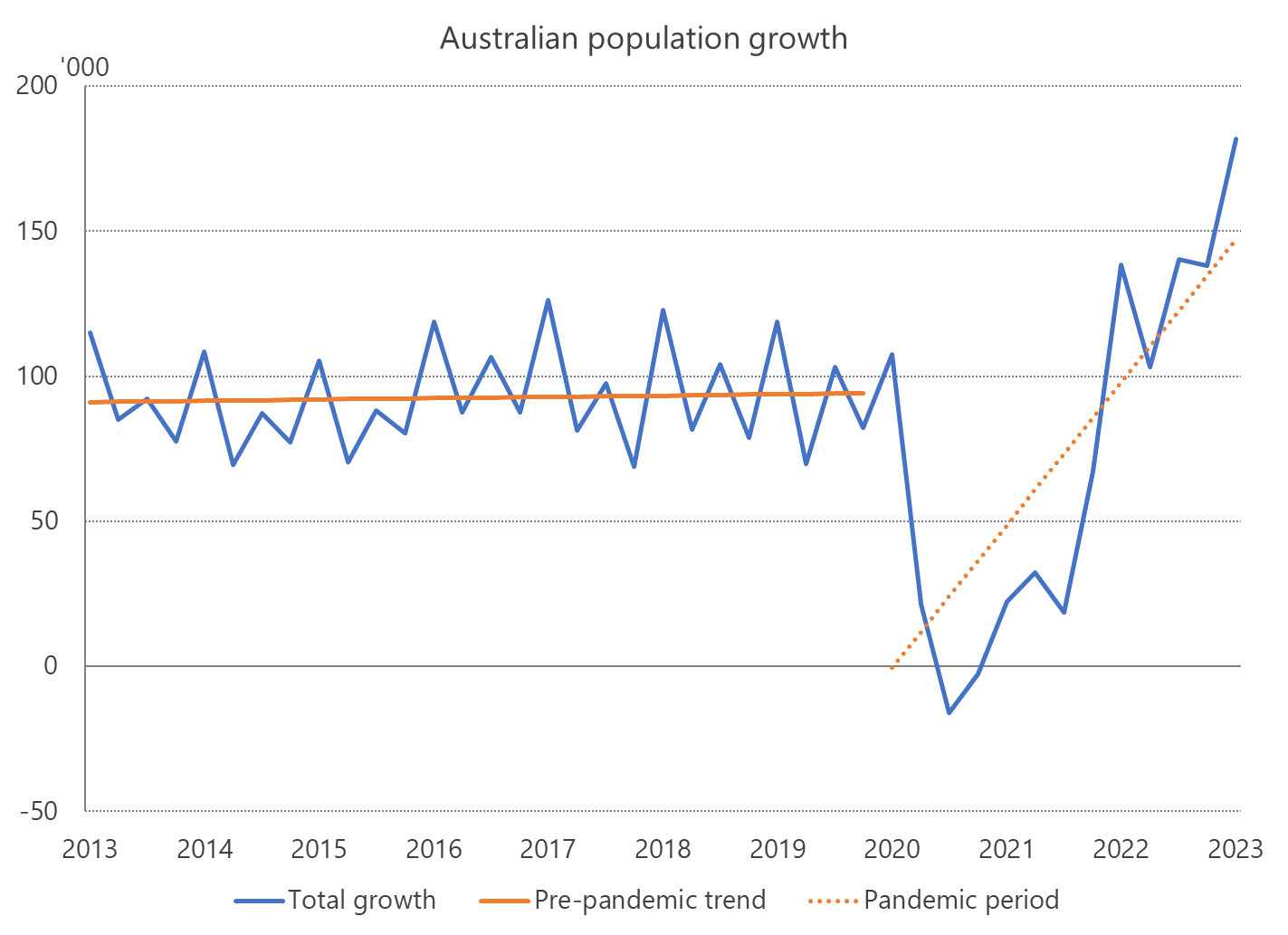

Chris has a point; our migration intake has been very high since about September 2022.

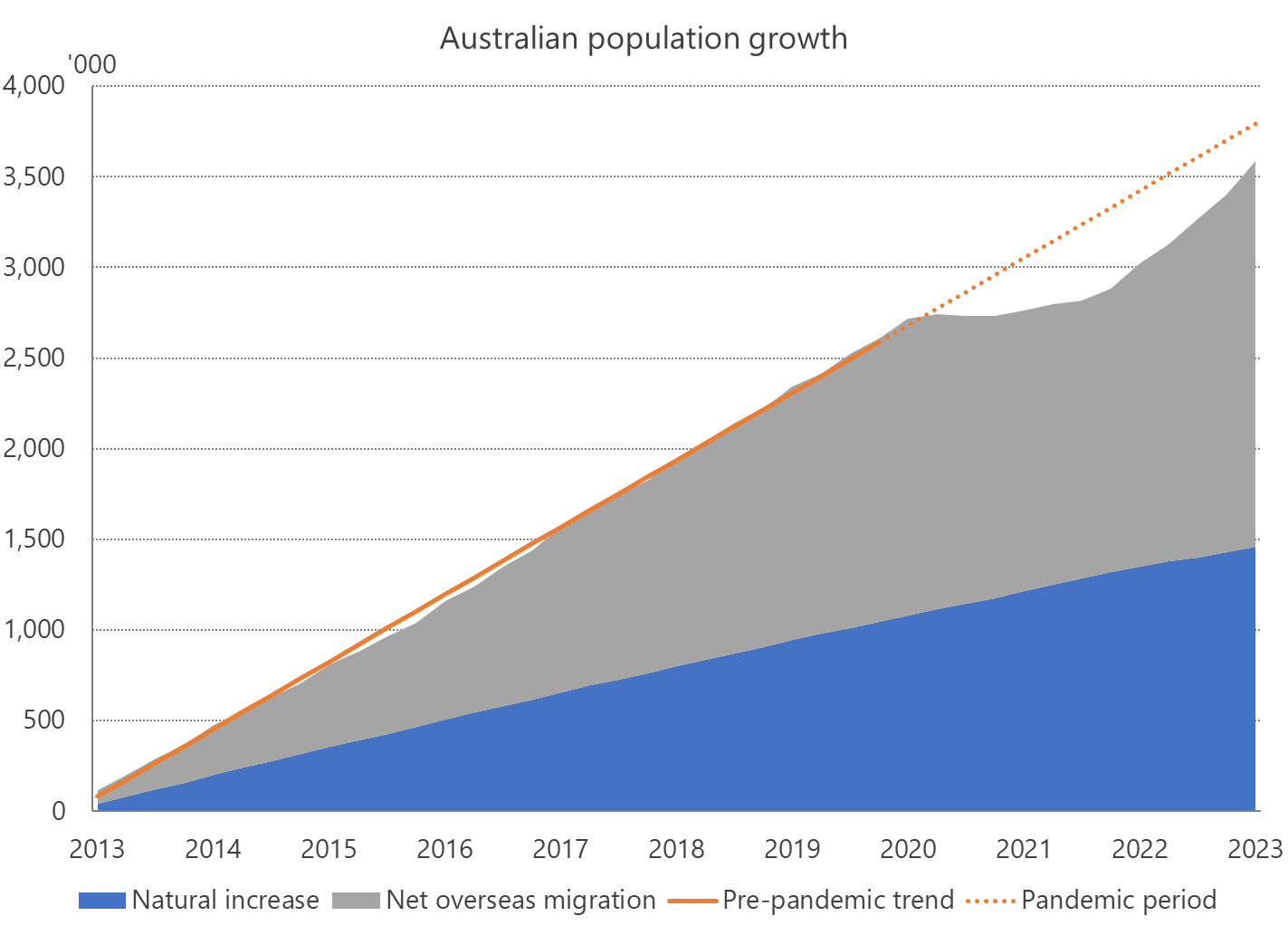

But how much of this is this simply ‘catch-up growth’? Notice the huge dip during the pandemic when our borders were closed – even if Australia’s migration policy remained unchanged, we should still have expected the rate of growth to eclipse the pre-pandemic trend for a time. For instance, students are coming back into the country to study in-person but there aren’t nearly as many departing recent graduates to offset them. The same is true for backpackers and other multi-year temporary visa holders. We won’t know for sure until we get the detailed data in mid-December, but we can examine the aggregates.

As of March 2023 (the last available data point), we were still around 250,000 people short of where we would have been based on the pre-pandemic migration trend. If the current rate of strong migration continues (around 50,000 people per quarter above the long-run), we’ll be back to trend by the middle of next year.

Time will tell whether Australia’s migration intake has actually moved to a higher level or if it’s all simply catch-up. But any policy advice that fails to acknowledge the fact it might only be temporary could do serious harm to Australia if it’s acted upon – not to mention the credibility it affords nationalists and other anti-migration types.

The right kind of migration is a good thing

There’s strong evidence that migration is a net positive for both migrants themselves, the recipient countries, and sometimes even the emigration countries (if there are large remittances). For example, Aubry, Burzynsi and Docuquier (2016) showed that:

“[R]ecent migration flows have been beneficial for 69% of the non-migrant OECD population, and for 83% of non-migrant citizens of the 22 richest OECD countries. Winners are mainly residing in traditional immigration countries; their gains are substantial and are essentially due to the entry of immigrants from non-OECD countries. Although labor market and fiscal effects are non-negligible in some countries, the greatest source of gain comes from the market size effect, i.e. the change in the variety of goods available to consumers.”

But just because most of us are better off, the harm it causes the other 17%, no matter how small, may not be worth the trade-off. There could also be longer-term costs that don’t get picked up by studies of “recent migration flows”, more than offsetting the benefits.

One of the more common complaints about migration I see on social media, the comment sections of news articles, and on contrary blogs, is the fear is that migrants will take local jobs or “smash wages”. It’s a claim that makes sense intuitively – adding more people competing for the same jobs will, all else equal, lower the price (wage) for that job, right?

But economists know to think beyond intuition, or what Frédéric Bastiat would call the ‘seen’. The claim that migrants will take jobs or reduce wages for locals falls into what is known as the lump of labour fallacy; the idea that there is a finite amount of work to be done. Not only is it a fallacy – migrants increase supply and demand, creating jobs – but serious researchers have also examined the data and haven’t found any evidence for it.

The most notable studies on migration and wages are from Nobel Prize winner David Card (1990; 2000; 2005), who found that the labour market consequences of unskilled migration in the US were “relatively small”, and had “no discernible effect on the wages [of natives]”. Card and his co-authors concluded that:

“[T]he local labor market impacts of unskilled immigration are mitigated by other avenues of adjustment, such as endogenous shifts in industry structure, rather than by rapid adjustments in the native population.”

In Australia, Crown, Faggian and Corcoran (2020) found a similar effect – or lack thereof – for low- and high-skilled migration. In fact [emphasis mine]:

“Our findings indicate that skilled international workers increase the wages of natives, and induce native workers to specialize in occupations associated with a high intensity of communication and cognitive skills.”

One important caveat is that these studies all looked at OECD countries, most of which are relatively wealthy compared to the global average. Australia and the US, in particular, have done well out of migration because they’re wealthy and stable enough to be relatively picky about the type of migrants they take in.

How migration can work well

Australia is a nation of migrants – around 30% of us weren’t even born here, and almost half of us have a parent born overseas. They have helped us grow and prosper, largely because “migrants to Australia have increasingly been young and skilled… [so have] softened the impact of Australia’s ageing population, boosted labour force participation, and increased the diversity of Australia’s workforce”.

A report by the Productivity Commission (PC) drew similar conclusions, finding that the “overall economic effect of migration appears to be positive but small”. The impact was small because:

- the annual flow of migrants is small relative to the stock of workers and population; [and]

- migrants are not very different in relevant respects from the Australian-born population and, over time, the differences become smaller.

To ensure migration policy works to the benefit of all, governments must ensure migrants can assimilate with the native population:

“English language proficiency stands out as a key factor determining the ease of settlement and labour market success of immigrants.”

Australia’s migration policy has, for the most part, achieved that. Now that could change, and there might also an argument for slowing migration due to political constraints, which was the point Chris Richardson alluded to earlier. For example, if politicians have slacked off on infrastructure investment, or have gummed up the housing market so that supply struggles to respond to any level of demand, then migration – especially if the migrants’ culture differs significantly from the native population – could fuel local angst and create political opportunities for those less than savoury individuals willing to exploit it.

Such a political backlash might result in even less migration in the future, so the smart play could well be to slow down and fix the mess first, avoiding potentially damaging consequences down the road.

Which brings me to…

How not to do migration

Not all migration produces net benefits. When you ignore the importance of culture and the ability of migrants to assimilate, you create social divisions that can bring a country to its knees. Enter Sweden:

“Sweden’s prime minister on Thursday said that he’s summoned the head of the military to discuss how the armed forces can help police deal with an unprecedented crime wave that has shocked the country with almost daily shootings and bombings.

…

“Sweden has never before seen anything like this,” Kristersson said in a televised speech to the nation. “No other country in Europe is seeing anything like this.”

Sweden has grappled with gang violence for years, but the surge in shootings and bombings in September has been exceptional. Three people were killed overnight in separate attacks with suspected links to criminal gangs, which often recruit teenagers in socially disadvantaged immigrant neighbourhoods to carry out hits.”

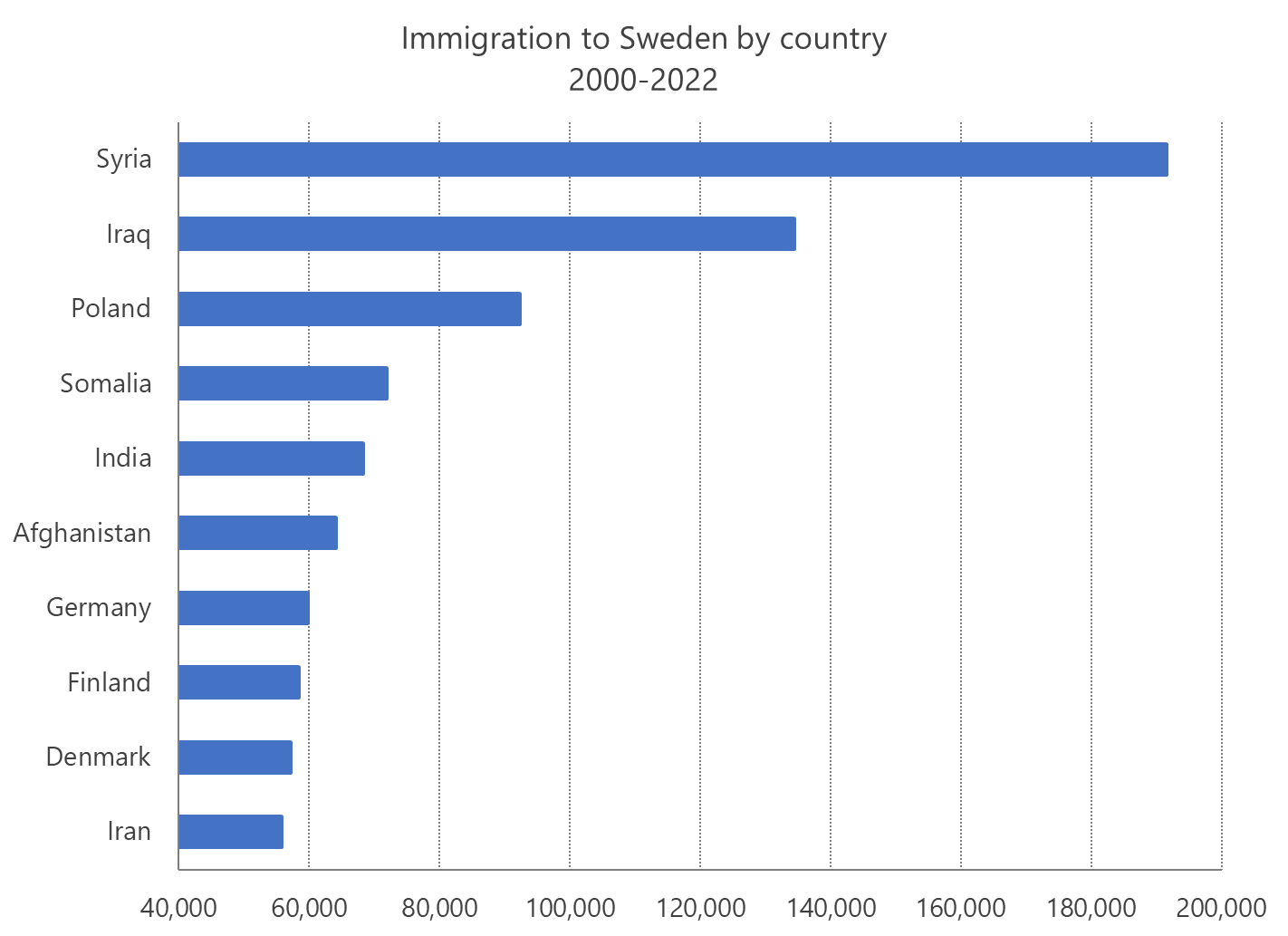

For decades Sweden has been taking in world-leading numbers of asylum seekers and refugees. Most of these migrants do not speak Swedish and have very different cultural and religious backgrounds to the native population, meaning they have struggled to assimilate.

A 2017 modelling exercise by the Pew Research Center found if Sweden continued to take in “even more refugees than the UK, Italy and France, all of which have much larger populations”, then by 2050 Sweden’s population:

“…could grow to 31% Muslim in the high scenario by 2050… because Sweden is home to fewer than 10 million people, these arrivals have a bigger impact on Sweden’s overall religious composition than does Muslim migration to larger countries in Western Europe.”

Data from Sweden’s statistical office shows from where Sweden’s migrants have been coming:

There’s nothing especially ‘wrong’ with Syrians, Iraqis, or Muslims in general. But when a small, culturally and religiously homogenous country like Sweden takes in a large number of disproportionately young, male and unskilled people with a completely different language, culture and religion in a short period of time, it’s a recipe for disaster. A path to crime and violence is an inevitability for many who see no future: in June 2021, the unemployment rate for Swedish born persons was 4.6%. For those foreign born it was a whopping 20.0%. It has since fallen to 13.8% (compared to 3.4% for the Swedish-born population) but is still well above where it should be in a well-functioning society.

In a democracy, that’s unsustainable: last year the Sweden Democrats party, a group that “oppose current Swedish immigration and integration policies”, secured enough votes to force the centre-right Moderates to rely on its support to win a majority in parliament. Sweden is now tightening its migration laws “to reduce the number of asylum seekers coming to Sweden”. Even before the election, the ruling centre-left party admitted its mistakes:

“Integration has been too poor at the same time as we have had large [amounts of] immigration… Segregation has been allowed to go so far that we have parallel societies in Sweden. We live in the same country but in completely different realities.”

Sweden’s experiment with unfettered migration appears to be over; so how can Australia avoid making the same mistakes?

Lessons from Sweden

Australia already has a fantastic migration policy by global standards: we take in relatively young, skilled people who have decent English proficiency. They pay more taxes and receive less welfare than the average Australian over their lifetimes, and their children don’t just regress to the mean but tend to “have higher incomes on average than Australians from similar backgrounds”.

So the first lesson would be don’t mess with a good thing. But that may not be possible – like Australia, fertility rates in Western European and East Asian countries are also in decline, so the pool from which we’ve historically drawn is diminishing (and we’re now competing with them for the best migrants!).

If Australia looks like it might start taking in large numbers of migrants from more culturally different places, such as the Middle East or North Africa – the UN predicts that “More than half of global population growth between now and 2050 is expected to occur in Africa” – then it’s something our policymakers should be proactive about. Migrants from those regions already have the highest rates of unemployment in Australia (7.5%), so what we’re currently doing isn’t working all that well.

Key barries to employment among migrants in Sweden include integration and language. A 2013 Swedish study by Malmberg, Andersson and Östh showed “the importance of segregation for [causing] urban unrest and support residential desegregation as a policy against such ‘micro-riots’ as the burning of cars”. Sweden’s government may have ignored that advice, but it’s not too late for Australia.

The idea of desegregation isn’t a new one; desegregation of migrants has been the policy of our enterprising neighbour to the north, Singapore, since 1989, via its Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP):

“The policy stipulated that the ratio of flats within neighbourhoods for the different ethnic groups: 22 per cent for Malays, 84 per cent for Chinese, and 10 per cent for Indians and other minority groups. Within each block, the ratio for flats was 25 per cent for Malays, 87 per cent for Chinese, and 13 per cent for Indians. These quotas have changed over the years, such as in 2010, where the neighbourhood- and block-level limits for Indians and other minority groups were raised to 12 per cent and 15 per cent respectively. Nonetheless, the principles remain the same.”

The EIP is not without its flaws, and it wouldn’t even be possible in a country like Australia with a strong democracy, property rights, and private housing (in Singapore over 90% of all land is state-owned and leased to citizens). Nevertheless, it’s an example of something that works relatively well, and even if we can’t replicate it we can try to achieve similar outcomes here with different methods.

If Australia wants to continue reaping the benefits of migration without the potentially large costs we’re seeing in similarly wealthy democracies like Sweden, then more work needs to be done to ensure the appropriate policies are in place before the door is opened. That means continuing to invest in integration programmes, language acquisition, and skills training for migrants to ensure they assimilate into Australian society and find gainful employment.

But arguably most importantly, it also means fixing the structural issues – e.g., housing affordability – that strain social cohesion. We desperately need zoning and occupational-licensing reform so that migrants can be affordably housed, and apply their skills productively rather than driving for Uber. Failing to address these issues makes migrants easy scapegoats for opportunists who want to close Australia off for good, potentially leaving us all worse off.

Member discussion