Is it time for housing coercion?

You would be hard pressed to find anyone in Australia who disagreed with the claim that our housing market doesn't work all that well. Where people will differ is in their proposed solutions.

For example, the federal Greens want to make it worse by introducing policies such as rent freezes. Also at the federal level, the Liberal party seems more interested in riding the nation's anti-migration sentiment to the election, rather than addressing the real policy drivers behind unaffordable housing. And federal Labor? Well, they've never met a problem that couldn't be fixed by simply throwing more money at it. In an article in The Australian, independent senator David Pocock observed that in its first seven months, the $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund "hasn't spent a single cent on new social and affordable homes".

What has it been doing? Spending $24m on external consultants and $6m in annual executive salaries. But despite those generous salaries, I don't envy the Fund's executives: they're effectively handcuffed, only allowed to hire "accredited" builders, leaving just 568 of the more than 400,000 Australian construction companies – a little more than 1% – eligible to work for them. In addition to the tiny pool of eligible workers, the Fund will also have to navigate the same constraints and construction cost inflation that has made it very difficult for market supply to respond to the housing crisis. Good luck building those 40,000 homes in just five years; you're gonna need it!

But then that's the problem with targets that focus on building houses rather than improving our capability to build houses, isn't it? There's no shortage of builders champing at the bit to build housing. The Housing Fund will face exactly the same obstacles that market-based developers do.

Our housing woes start close to home

Then there's local government, for which I have no hope. I live in a relatively old part of Perth (by WA standards), where kilometres of well-located and largely unchanged houses are preserved by arbitrary density caps. The other week I received a letter from my local council advising me that those density caps were not enough to "conserve the character and features of the area", and they wanted to designate a few blocks as "Heritage" to ensure that any new development would be "sympathetic to the significance of the area".

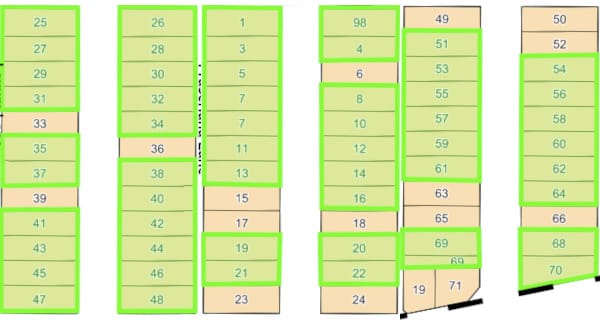

When I looked at their map to see which blocks were considered so important to warrant such restrictions, it quickly became clear that this was nothing but a thinly veiled attempt to thwart any attempt at development. The green blocks on this sample street below are the ones council deemed worthy of additional protection (I've cut it in three to make for easier viewing):

If you add them up, nearly 80% are supposedly "heritage" worthy! Now, Australia is a relatively new country, and Perth is an even newer city; we're not talking about building skyscrapers in central Paris here. Most of these houses are old in the bad-kind-of-way, and are largely unremarkable.

On its website, the council was quick to reassure residents that its plan wouldn't affect home values – phew! In fact, they assure us, it's probably going to make these pricey blocks even more expensive:

"Numerous studies and experience from other western suburbs local governments and cities across Australia have shown that Heritage Areas are either neutral or positive for home values. This is because once Heritage Areas are established, they become an attractor for people who love these areas and are willing to pay a premium to live in an area that is unlikely to become substantially redeveloped."

That attitude is precisely the problem! It's why, in the context of fixing our housing crisis, I have zero faith in local government. As Harvard's Jason Furman has observed, when locals try to "safeguard" their assets by making it more difficult to build in an area, "some individuals are priced out of the market entirely, and homes in highly zoned areas also become even more attractive to wealthy buyers":

"Thus, in addition to constraining supply, zoning shifts demand outward, exerting further upward pressure on prices and thus also, economic rents."

All governments can be captured by special interest groups, but local governments are especially vulnerable given their much smaller size and relative lack of... talent. Designating large parts of a suburb "heritage" is a sign the council may have been captured, given such designations are frequently as a pretext to restrict competition, maintain monopoly rents, and keep suburbs frozen in time for the benefit of a few at the expense of the many.

Another recent example of this effect was in NSW. While our post-pandemic surge in migration was mostly catch-up and will soon fall back to more normal levels, it did bring attention to students and the strain they can put on our housing markets. So some of our universities, being the cashed-up, inner-city land barons that they are, tried to respond by building more student accommodation. Only for the local council to get in the way:

"Referring to the UNSW proposal, Randwick's Labor Deputy Mayor Alexandra Luxford said: 'This monstrosity of an overdevelopment on such a small site is just appalling, and it's terrible that the university continues to think they need more accommodation throughout Kensington when no housing for the regular punters is being built'."

Luxford then went on to say that "she had seen news stories in which students were queuing with non-students for market rentals, which indicated that existing student housing was too expensive".

So... the university wants to build more student housing, yet Luxford objects because it's too expensive, asking "why are we building more?". She quite literally doesn't understand basic economics, i.e., that for a given demand, increasing housing supply will reduce prices for students and "regular punters" alike.

Such attitudes permeate through local governments and are a major reason why restrictive zoning persists, driving up house prices. In Australia, "as of 2016, zoning raised detached house prices 73 per cent above marginal costs in Sydney, 69 per cent in Melbourne, 42 per cent in Brisbane and 54 per cent in Perth".

A new paper from housing experts, including Harvard's Ed Glaeser and colleagues, found that zoning also reduces the size of building companies, "which limits their ability to reap returns from scale and their incentives to invest in technology". Smaller firms are also less productive, making it more expensive to construct housing.

Add to that the fact that local government planning schemes can differ considerably across jurisdictions and it's very hard for residential property developers to achieve the economies of scale needed to keep a lid on construction costs.

More of the good stuff, please

Luxford's objection to UNSW's 15+ storey apartment complex is a common one. It's so costly to buy land zoned for density (which sells at a premium) and then to get through the many layers of development approval that it's often only such large-scale developments that can afford to go through that process. Melbourne architect Michael Smith recently lamented how long it takes to build something these days:

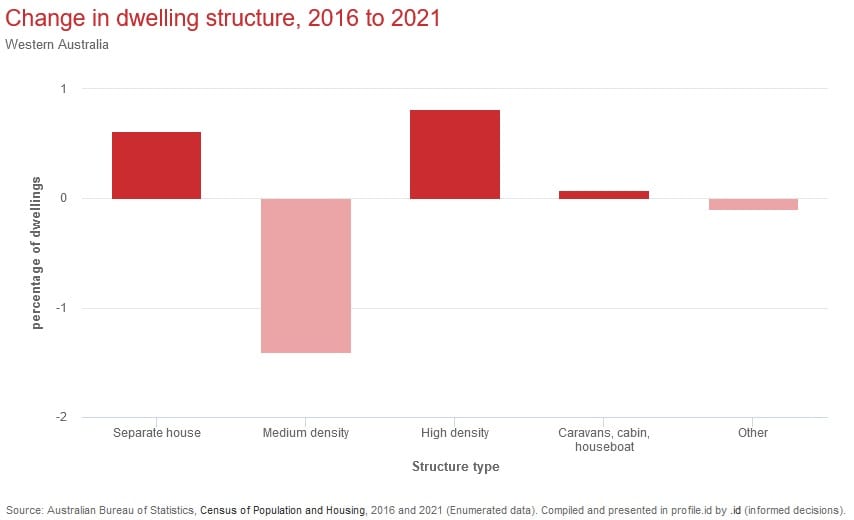

In my home state of WA, the share of high-density buildings increased between 2016-2021, but so too did single detached dwellings. Meanwhile, the share of medium-density housing – arguably the most needed and least objectionable type of denser housing – fell:

No doubt, apartments must play an important part in the housing mix. But going from an ocean of single detached dwellings to monstrous apartment buildings, with nothing in between, is one reason why people oppose development and changes to zoning laws. And it's why our cities tend to look like this:

Sure, people like having space. But that's only part of it; it's also because zoning and the endless maze of local government rules and restrictions hollows out everything in between, leading to the so-called 'missing middle':

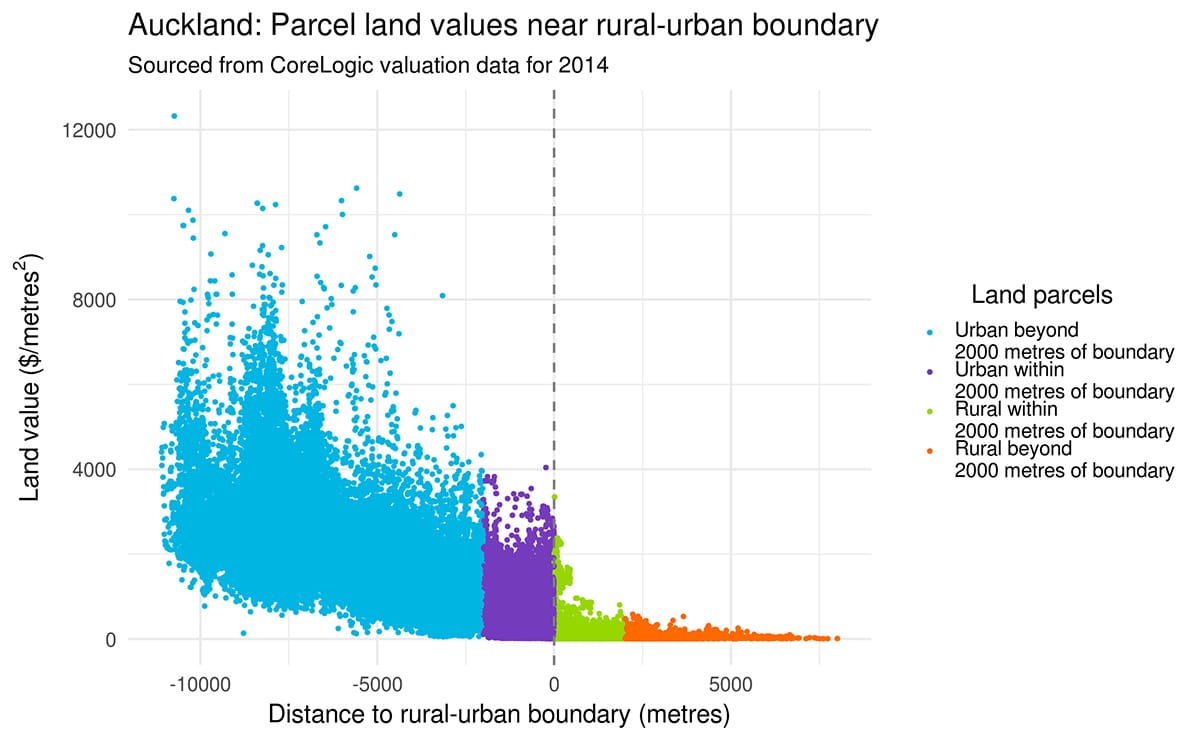

Such restrictions also raise prices. Just look at the price discontinuity of properties at the zonal boundaries between urban and rural land in Auckland:

Land further away from the city centre should be cheaper, but the dramatic decline at the rural-urban boundary is a sign that there are "constraints for urban growth", i.e. rules preventing it.

Speaking of Auckland, zoning deregulation undertaken several years ago is starting to make housing more affordable. Some of New Zealand's media are now even running articles asking questions like What's hurting Auckland's housing market?, with investors noticing an "oversupply":

"Look at how many two-bedroom townhouse listings there are in south Auckland, it's nuts. Developers are doing many deals right now."

The horror! But in all seriousness, that's exactly what is needed to fix the housing crisis in Australia. A market where "a big rise in construction especially among the new build sector, townhouses... [creates] choice for buyers", easing prices and improving affordability.

Also in New Zealand, the capital city of Wellington recently passed a new housing-friendly District Plan, and "resource consent applications for multi-unit developments have surged... with more applications over the past month for multi-unit developments than in any other month of the year".

Reform state and local planning laws and get a building boom; it's really not that complicated. The Kiwis have shown that it is possible to achieve zoning changes and affordable housing through local government. But if that fails – as it seems to have in many parts of Australia – it might be time to try a bit of housing coercion.

We should be more like Japan

A recent UCLA podcast had a look at why countries such as Japan don't suffer housing crises. While it's obviously far more complicated than I can explain in a couple of paragraphs, the summary is that in Japan, people are allowed to build. There are 12 national land use zones for the entire country, rather than the mix of state-based zoning combined with local planning schemes for every suburb that we have in Australia. Even the most restrictive zone "allows schools, shrines, temples, churches, and clinics... [and] small ground-floor commercial uses in essentially any home".

There aren't really height restrictions, just limits on how much a building can obstruct sun exposure for your neighbours. There are no minimum parking requirements. No minimum lot sizes. A downside has been "the loss of green spaces on people's properties", and perhaps not enough parks and open spaces, but given that Australia's cities are over ten times less dense than Tokyo, it's not like we couldn't prevent that from happening here while still making homes significantly more affordable.

But the key feature is that it bypasses local government:

"I think there are downsides to this approach, as with any, but one strength is that you don't need planners setting arbitrary requirements parcel by parcel, which may be too protective of neighbouring parcels in some cases and not protective enough in others. The Japanese approach to this, which isn't at all unique to Japan, manages to treat everyone the same, or at least aspires to, holding them all to the objective standard."

Now, not all local governments are opposed to density. And not all states governments understand that supply is important in solving this crisis. For example, the South Australian government recently offered a bunch of first home buyer incentives which will only add to demand, for the benefit of "the sellers who receive a higher sale price". Queensland's government is perhaps even more clueless.

Still, states are the best placed to solve the housing crisis because of how our constitution is structured; the federal government has no control over land-use zoning and cannot directly fund (or punish) local governments. But where states are the problem, such as when they maintain overly restrictive Residential Design Codes in well-located suburbs, the federal government could offer incentives (grants) to change them for the better.

For example in WA, where medium density is permitted, the state planning system incentivises developers "to knock the old dwelling down, remove all the trees and put a triplex on it", because doing so allows them to avoid the local council's scrutiny – a process that can add six to nine months to the project and up to $60k in holding costs. That then (rightly) pisses off the locals, "and dissipates the impetus developers require to deliver medium-density projects".

Lose, lose; sometimes what's needed is just a bit of common sense, which for whatever reason often gets lost in state politics.

But in the meantime, it's not all a lost cause: some councils can be convinced. Tamatha Paul, a Greens councillor from Wellington, advised fellow politicians that in her experience "a majority of people support densification":

"You have seen pro-density representatives at all levels be elected and re-elected because the mood of our city is overwhelmingly that we want more housing and we want it now. Do not be scared of a vocal, privileged minority who seek to protect their own interests. I promise you that the voice and the power of the people – real people – is so much stronger."

See, the Greens can be good on housing!

Similarly, NSW's upper house whip and Liberal party member Chris Rath told his colleagues that "you're not going to lose your seat because of 10 letters that you receive [about] a development from a few NIMBYs that don't want it to go ahead".

And there's evidence to support these anecdotes: a study published in February on upzoning in New Zealand's Wellington region found that when a local government sought voluntary feedback, just 44% wanted medium density housing. But when the entire suburb was polled, that figure rose to 69%, "consistent with self-selection bias in voluntary submissions".

So, there is hope; most people actually do want additional medium density and for the 'missing middle' to be found. We just have to overcome the collective action problems that too often capture local governments, and one way to do that might be to take a more coercive, top-down approach to land use planning where those forces are not as strong, such as at the state and federal levels.

Member discussion