Javier Milei's shock therapy

I'm going to venture out beyond our borders today because what's happening in Argentina is quite possibly the wildest reform experiment the world has seen... ever. And believe it or not, the results could offer some important lessons for Australia.

A bit of background

For those who have recently returned from a well-deserved summer break, a month ago Argentina elected a libertarian economist, Javier Milei, to the Presidency. It was a convincing but by no means resounding victory – Milei secured just 30% of the general vote, and then won a head-to-head against the incumbent government's Perónist (left-wing) candidate with almost 56% of the vote.

Not since Chile's Chicago Boys has South America experienced a shock quite like this. Since becoming President on 10 December 2023, Milei:

- Issued an emergency mega-decree with over 300 measures that significantly deregulate the economy and balance the budget in 2024, equivalent to over 5% of GDP.

- Introduced a 664-article omnibus bill to Congress that "would drastically expand presidential powers [until the end of 2025] and affect a wide range of policy areas". According to Milei, this contains around two thirds of his planned reforms.

- Met with IMF representatives and agreed to "restore macroeconomic stability", freeing up US$4.7 billion of the more than US$31.1 billion funding agreement the IMF has with Argentina.

- Announced that the country will join the OECD.

- Plans to dollarise the economy, ditching the peso and closing the central bank, but that has been 'set aside' for now.

Last week, Congress began its debate on Milei's Omnibus Law. Milei has nothing close to a majority – his party holds just 39 of 257 seats in the lower house, and just 8 of 72 seats in the senate, making him "the weakest president in Argentina's history". While he might have the support of former centre-right president Mauricio Macri, it won't be enough without persuading a few centrists to his cause, too.

Milei's party wants the bill to be signed by the end of January. Somewhat amusingly, Nicolás Mayoraz, president of the Milei's Affairs commission, proposed a full work week to get it done: "Here we know that the custom is to work from Tuesday to Thursday and we are going to try to work from Monday to Friday."

On the road to nowhere for a century

The environment in Argentina was ripe for change, which is saying something given that it's a country which has tolerated poor governance since at least 1940:

"Since the rise of Perón in the 1940s, democratic Argentina has been dominated by the political party he created, the Partido Justicialista, usually just called the Perónist Party. The Perónists won elections thanks to a huge political machine, which succeeded by buying votes, dispensing patronage, and engaging in corruption, including government contracts and jobs in exchange for political support. In a sense this was a democracy, but it was not pluralistic. Power was highly concentrated in the Perónist Party, which faced few constraints on what it could do, at least in the period when the military restrained from throwing it from power."

Disciples of Perón have maintained almost complete control of power in Argentina ever since, most recently by presidents Néstor Kirchner (2003-07) and his wife, Cristina Kirchner (2007-15, then again as VP from 2019-23). These years were marred by recurring fiscal crises – I've been to Argentina a few times and was only semi-joking when I would tell people that it's a good country to visit about once a decade, right after the next inevitable fiscal crisis (the steak and wine are top-notch).

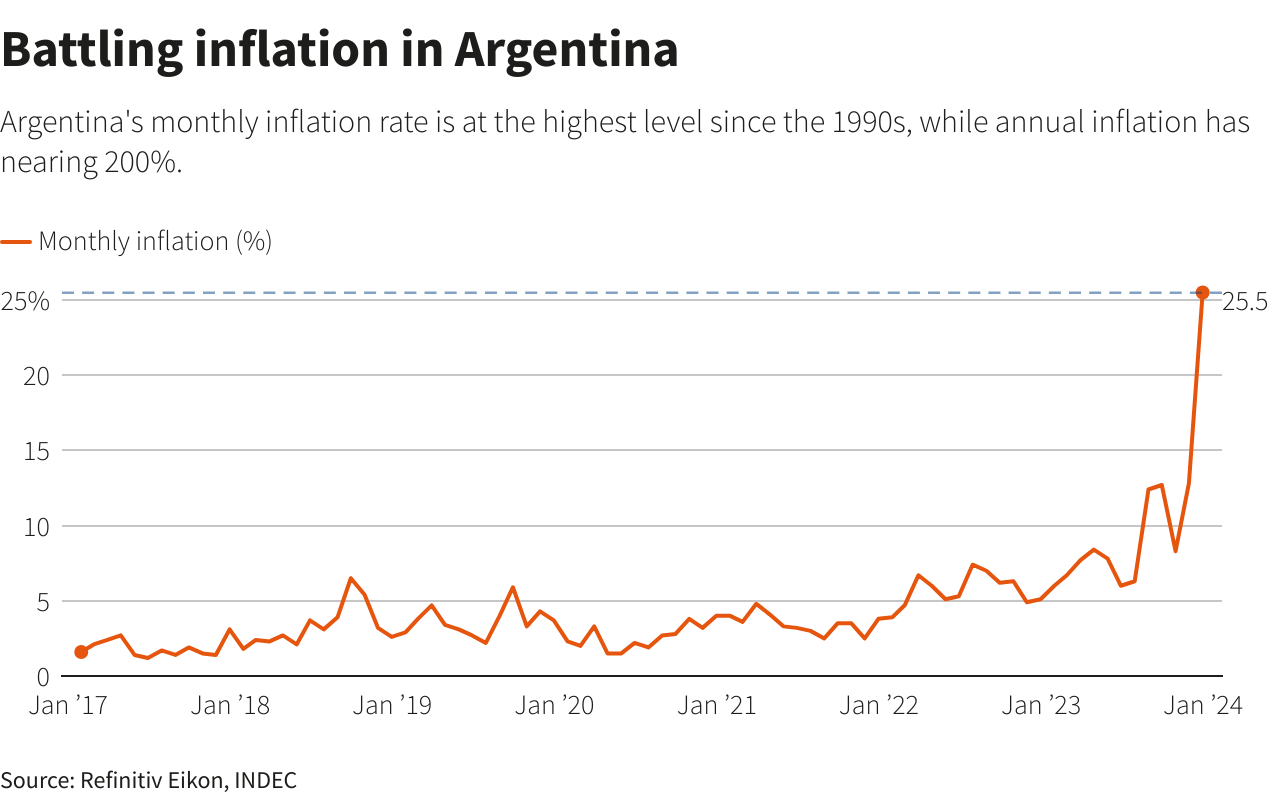

But by 2023, the situation had really got out of hand, even by Argentina's standards. Inflation rose at a rate of over 200% in just a single year in 2023 – the highest for 32 years, surpassing even Venezuela – with more price increases expected: the previous government had been printing up pesos to finance its promises, relying on price controls to temporarily hide that fact from the population.

Milei promised a drastic alternative, and voters had finally had enough to roll the dice.

Can Milei succeed?

In a word, yes. But it's not economics that will determine whether he succeeds in dragging Argentina out of the depths that three generations of Kirchner's, and the many other Perónists before them, have inflicted on the country.

It's politics.

While it's true that Milei is taking a metaphorical chainsaw to Argentina's regulatory apparatus, everything he has passed so far has been achieved via executive orders – a method also used by his Perónist predecessors – not through the 'proper' channel of Congress. Milei will also face a battle in the courts, which have already blocked his proposed labour reforms. While he has yet to go down this path, the tradition in Argentina has been for presidents to effectively assume control of that apparatus:

"In 1990 Argentina finally experienced a transition between democratically elected governments—one democratic government followed by another. Yet, by this time democratic governments did not behave much differently from military ones when it came to the Supreme Court. The incoming president was Carlos Saúl Menem of the Perónist Party. The sitting Supreme Court had been appointed after the transition to democracy in 1983 by the Radical Party president Raúl Alfonsín. Since this was a democratic transition, there should have been no reason for Menem to appoint his own court. But in the run-up to the election, Menem had already shown his colors. He continually, though not successfully, tried to encourage (or even intimidate) members of the court to resign. He famously offered Justice Carlos Fayt an ambassadorship. But he was rebuked, and Fayt responded by sending him a copy of his book Law and Ethics, with the note 'Beware I wrote this' inscribed. Undeterred, within three months of taking office, Menem sent a law to the Chamber of Deputies proposing to expand the Court from five to nine members."

To succeed as a political outsider in Argentina will be a tall order: Milei needs to convince the moderates in Congress that his shock therapy will be temporary; after all, he is quite literally seeking control of both the executive and legislature, allowing him to completely bypass Congress for two years, with an option for two more. That kind of power can lead to some very, very bad consequences if misused (look up the Enabling Act of 1933 if you want to see where I'm going with this).

Milei's also going to have to confront public opinion at some stage this year, which could turn against him. Argentina doesn't have a simple Band-Aid that needs to be ripped off; it needs entire limbs cauterised. That will be painful, and not just to regular voters but also to the elites to whom Argentina's policies and institutions were designed to transfer wealth. The folks over at the Peterson Institute for International Economics have run a few scenarios and don't expect any kind of movement towards economic stabilisation until the end of the first quarter of 2024. Even their "Goldilocks scenario" doesn't have inflation reaching between 15-30% by "the end of 2024 or the first half of 2025".

Finally, Milei will need to avoid being assassinated (there was an attempt on Cristina Kirchner in 2022) and keep the military on side for long enough to dodge a coup d'état – Argentina has already had six of those since 1930!

Needless to say, the odds of Milei pulling this off and breaking Argentina's century-long slump are low. The country's bonds remain deeply distressed, trading at 30-40 cents on the dollar, the peso continues to fall on the black market, and its largest labour union has called for a disruptive nationwide strike on 24 January. Argentina's labour unions have been central to ensuring power and wealth remained in the hands of the country's elites:

"They are powerful, and enduring, often run like family businesses. Take the truckers' syndicate. It has had the same boss, Hugo Moyano, for 36 years. His oldest son is installed as the union's co-chief. A daughter and another son sit on the board, while a different son ran a separate union established for toll workers. He then became a congressman. The family has owned football clubs and runs a political party. They have been investigated for corruption, money-laundering and fraud, but few investigations have ended in charges. The Moyanos, who can freeze the transport of food and petrol around the country, have hitherto seemed untouchable."

Whether Milei manages to pull off his shock therapy, it has at the very least revived the idea of reform, which is something that has been sorely lacking in another country whose name starts with an A: Australia.

Lessons for Australia

Australia is not even close to being a basket case like Argentina, but we haven't done all that much in the way of reform for nearly 40 years (yep, Hawke/Keating was that long ago). Milei's proposed reforms are extreme, as they need to be: this is a country that grew reasonably well until around 1920 – largely because of its agricultural exports during a global commodity boom, rather than any kind of dynamism (sound familiar? cough iron ore) – and then languished for more than a century.

But many of Milei's reforms are quite sensible, and could plausibly unlock rapid productivity improvements Down Under. For example, the deregulation of air traffic. If you're as fed up with Qantas as I am, this is one we could immediately transplant here:

- An 'open skies' policy so that any foreign airline can operate in the country (provided they meet the same safety standards), increasing competition.

- Privatising Aerolíneas Argentinas and eliminating unprofitable routes.

- Repealing minimum prices for flight tickets, which forced airlines to charge higher prices so that Aerolíneas Argentinas could compete.

Less than a month after those rules were changed, four new routes have already commenced or been announced by competing Argentinian, Chilean, Brazilian and Paraguayan airlines. No doubt more will follow once investors have confidence that it will be a permanent reform – Congress may yet toss it out, and they can be challenged in court.

Back at home, there's a reason we only have two major domestic (non-regional) airlines in Australia, and it's not because airlines don't want to fly here: it's because we have rules prohibiting them from doing so. We also limit how often international carriers can fly to each city, leading to wasteful 'ghost flights', where carriers fly nearly empty planes on domestic routes for which they legally can't sell tickets. Worse, who gets the available capacity is not determined by market forces but by government fiat, leading to disputes such as this:

"Virgin Australia and Qantas are fighting over who will be awarded some lucrative flights to Bali, and the former says handing those services to its larger rival will weaken competition on the popular route.

...

The allocation of flights to big airports is exhausted on the Australian side of the agreement with Indonesia, prompting hopes that the agreement will be expanded. Other carriers in countries such as Vietnam have been pushing for an "open skies" agreement with Australia to facilitate more travel. The current air services arrangements provide for 25,000 seats per week for passenger services between Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane or Perth and Indonesia."

It's a worrying sign when Vietnam, which is quite literally governed by the "Communist Party of Vietnam", is more pro-market and competition than our own government. Our federal government may like to talk a big game on the importance of competition, but its own Ministers are still actively blocking it from happening in air travel.

So while Milei's approach to reform is extreme and unnecessary for a relatively well-functioning, wealthy democracy with (until recently) low and stable inflation such as Australia, that doesn't mean some of his reform ideas shouldn't be tried here. In fact, if we want to ensure we remain prosperous, then new ideas are exactly what are needed to reduce our dependence on a handful of commodities and lift productivity growth up from its 60-year lows.

Member discussion