Let's not make the housing crisis even worse

I trust everyone has now taken in yesterday's Budget. I was surprised by it, but only because from a macro point of view it was worse than I expected: net debt will continue to rise in every year, including by over $50 billion in 2024-25 and $60 billion in 2025-26, as Treasurer Jim Chalmers decided to add more than $24 billion of new policy-related spending, mostly in those years. As a share of GDP, that's a 2.9 percentage point increase in net debt in just two years.

Quite shocking, really, given our capacity-constrained economy, with unemployment is below 4% and the ongoing inflationary cost-of-living crisis partially caused by excessively loose fiscal policy.

On that note, Chalmers had the chutzpah to claim that the $300 energy rebate and 10% increase to the maximum rate of Commonwealth Rent Assistance will cut inflation over the next two years. Now, those might be things worth spending on, but unless cuts are made elsewhere they're going to add to inflation, not reduce it. I know that, the Treasury knows that, and the RBA will certainly know that when the time comes to consider its next rate decision. The only thing such spending will reduce is measured inflation because of how the stats bureau calculates the CPI. The claim is nothing but a pure, unadulterated attempt at deception.

But enough about the Budget.

Barely a day goes by without someone out there claiming to have an idea that will solve some complicated issue. Usually they do no harm; it's just some fringe academic, media personality or politician, whose ideas are rightly ignored, or – should they gain enough traction – appropriately dismissed based on of the harms they will cause.

But sometimes those ideas can become infectious, especially when they're latched onto by influential people with power. The most extreme example was perhaps a once-obscure German scribe called Karl Marx, who was elevated into the mainstream following the 1917 Russian Revolution:

"Lenin's political rise simultaneously enabled a sizable boost to the academic study of Marx's doctrines... While other factors certainly shaped Marx's reception in the mid-twentieth century, including the diaspora of the German-speaking academic Left in the face of Nazi persecution, the catalysing event in the elevation of Marx's intellectual stature appears to be the Russian Revolution."

Scholars of Marx who found themselves in positions of power, from Lenin to Mao, have subsequently caused millions of lives to be lost.

Closer to home and much more recently, the 'latest idea' appears to have taken hold in South Australia. I speak of psychologist Jonathan Haidt's theory that social media is causing stress, anxiety, and is even leading some of our kids to kill themselves (all of which I covered in last week's Fodder).

Despite evidence that Haidt may be barking up the wrong tree, Premier Peter Malinauskas has already embraced the theory, seeking to "ban social media for kids under the age of 14".

Malinauskas would have banned social media already if he could; he's just not sure whether he has the legal authority to do so.

Haidt's book, The Anxious Generation, has been out for less than two months, yet already it's informing policy in Australia. And while Haidt's theory is alluring in its simplicity, it has not stood up to initial scrutiny and should be studied further before policy conclusions are drawn, as a reactionary approach may cause large unintended consequences.

But Malinauskas' rapid embrace of a contestable theory provides a good case study as to why it can be dangerous to dismiss ideas on facts alone. Someone, somewhere in a position of power might actually do it – consequences be damned.

Which brings me to housing.

Australia's dual housing crises

Yesterday's Budget went to great lengths discussing what it planned to do about Australia's ongoing housing crisis, with an entire statement dedicated to "Meeting Australia's Housing Challenge". Most of it had already been announced, with $6.2 billion allocated to "new initiatives", including for social housing, state infrastructure improvement, and student accommodation.

The statement itself was actually quite good in that it (finally!) acknowledged that demand-side solutions were counterproductive:

"Productivity Commission research has suggested that for government programs assisting households to purchase a home, the assistance is likely to be capitalised into house prices when not accompanied with an increase in supply. This tends to benefit sellers and existing owners, rather than buyers, which in turn further prices low- and middle-income households out of owning their own home."

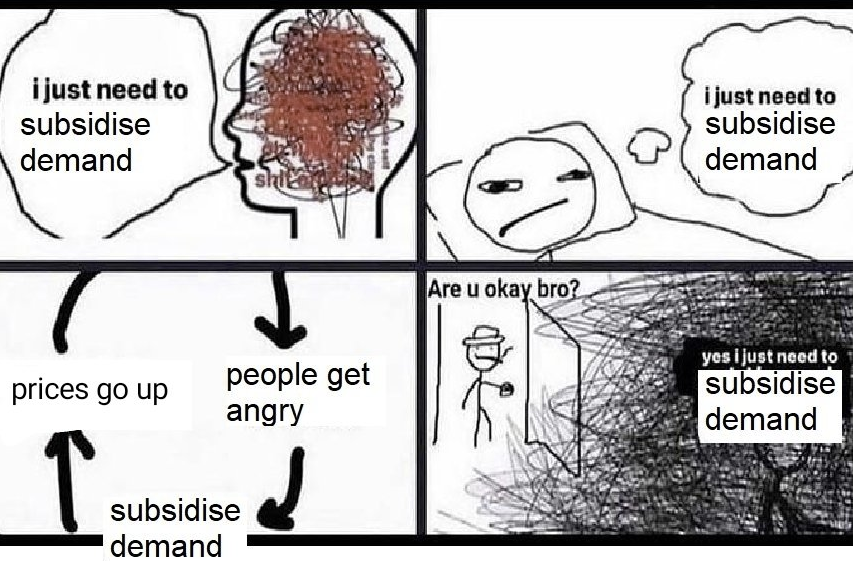

I'm reminded of this meme:

But despite a reasonably strong focus on the supply side – which is so much better than our tried-and-failed demand side solutions, such as first home buyer grants – I don't think that the government's approach will do all that much to solve the housing crisis.

The main reason why I think it will fail is because we have two housing crises in Australia at the moment: a long run supply issue and a short run demand and supply issue, and the government is not adequately addressing either of them.

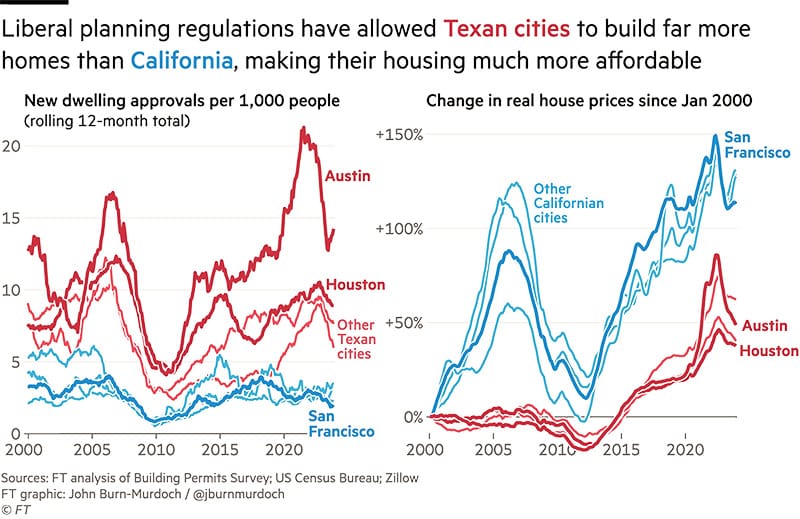

The long run issue is every housing economist's favourite gripe: land-use zoning laws. There is considerable evidence that in the long run zoning is the key driver of house prices in urban areas. Take this FT chart from two cities in the US, which shows two very different housing outcomes:

Nearly 70% of Australians live in a capital city, which is where zoning is most impactful: houses are considerably more expensive because of those restrictions, and up to 70% of the cost of a home in an urban area can be the result of the 'permission slip' effect, i.e. regulatory and zoning restrictions.

In Australia, zoning restrictions have been in place since at least the 1960s, when we – along with the rest of the anglosphere – decided to strike a balance between an individual's rights and that of the community's:

"A primary justification for public intervention through the land use planning system relates to the potential negative impacts, or 'externalities' of an individual's activities in the private use of land upon neighbouring landholders and the broader community."

As part of that process, property rights were partially transferred from existing land owners to wider communities via zoning. The problem is that over time, that balance became skewed in favour of existing owners within those communities, to the detriment of everyone else. Recent empirical evidence is clear that the negative externalities associated with higher density "are not nearly large enough to justify the costs of regulation", and that large transfers are being made to those fortunate enough to have bought at the right time:

"The dispersion in net housing worth has grown over time among this older cohort. In 1983 for example, the 95th percentile home equity value was 4.05 times the median value ($353,190/$87,120~4.05); in the 2013 data, the analogous ratio is 13.33 ($400,000/$30,000). We do not know where wealthiest 5%-10% of 45-54 year olds live, but the data are consistent with local land use restrictions leading to wealth transfers to older households who were fortunate enough to buy before binding regulations were imposed."

But that doesn't explain why house and rental prices shot up so dramatically following the pandemic. It's still closely related because of how the housing market has had to evolve around our zoning laws, but it's far from the whole story.

Building out, not up

In the past, we've managed to (partially) build our way out of the constraints of land use zoning by quite literally building out to the urban fringes where land is considerably cheaper as a proportion of total housing costs. But that's not sustainable; eventually, we run out of land or reach the point where people don't want to commute that far.

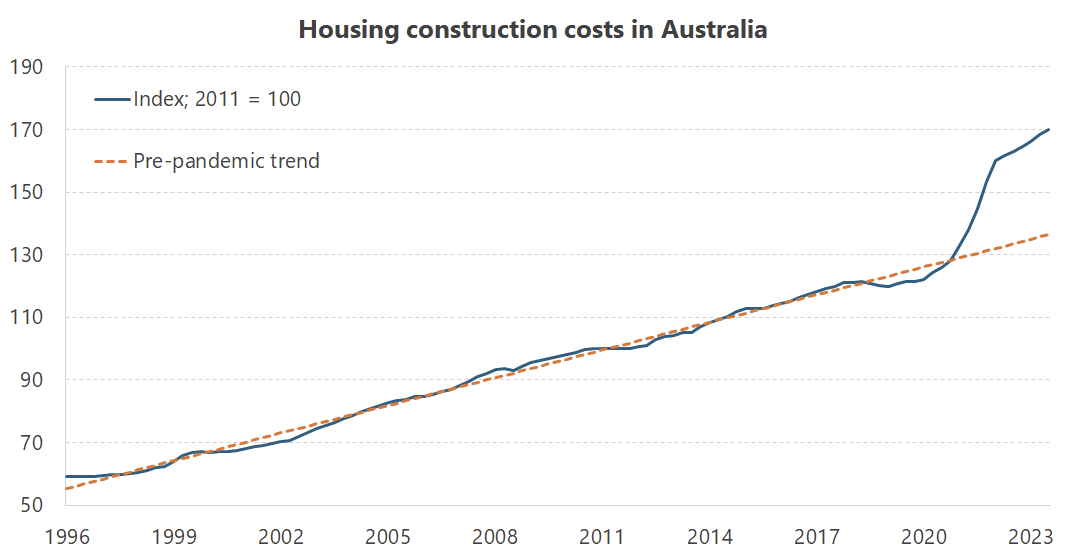

But that 'solution' also left us exposed to sudden increases in construction costs. I suspect a big part of the current housing crisis, which is distinct from the long run crisis that flows directly from zoning restrictions, is the result of this distinction between new urban fringe construction and construction within established suburbs. The latter has always been an expensive place to build because the zoning-related land costs make up the majority of the total cost. But in recent years, it's at the urban fringes where construction costs make up over 80% of the total cost where it has suddenly become relatively more expensive to build.

The cause of the spike in housing construction costs started with pandemic-related supply constraints driving up the cost of materials, and was followed by the government's excessive aggregate demand stimulus, which effectively poured gasoline on the fire. Another mining boom and state governments investing record amounts into public infrastructure didn't help matters either, as both effectively bid workers away from housing construction.

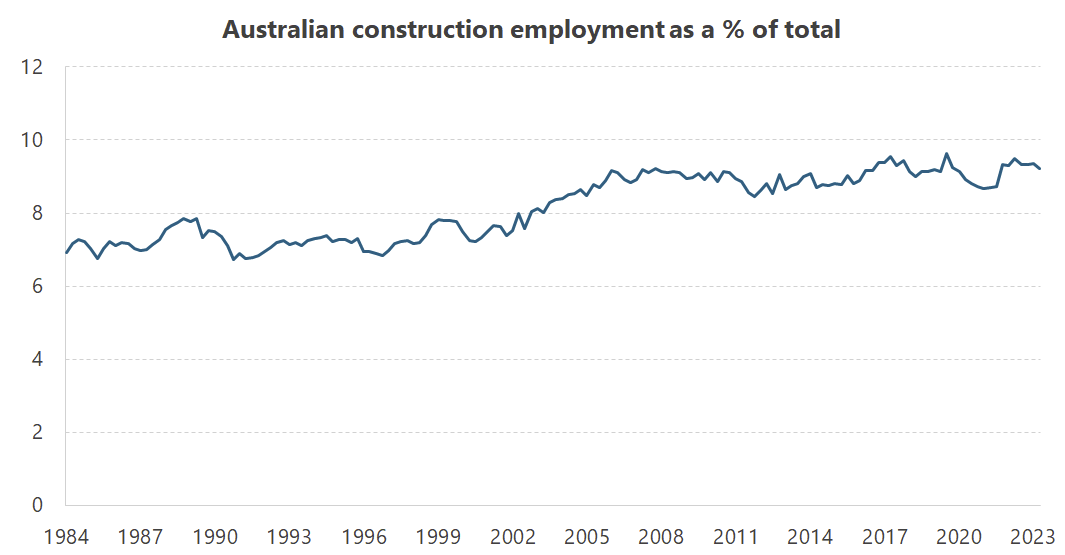

At the same time, some of the pandemic's working from home culture 'stuck', so average household size fell to new lows (it was already in decline because we're having fewer kids), and we had a bunch of catch-up migration as students who were locked out for two years started coming back but there were no graduate departures to offset them. We also had a relatively muted labour market response considering the demand for homes, with the share of Australian workers in the construction industry largely unchanged since 2007.

Put it all together, and we added to structural demand at the same time as houses got more difficult and expensive to construct in places where people are actually allowed to build them without prohibitively high land costs.

A perfect storm, if you will.

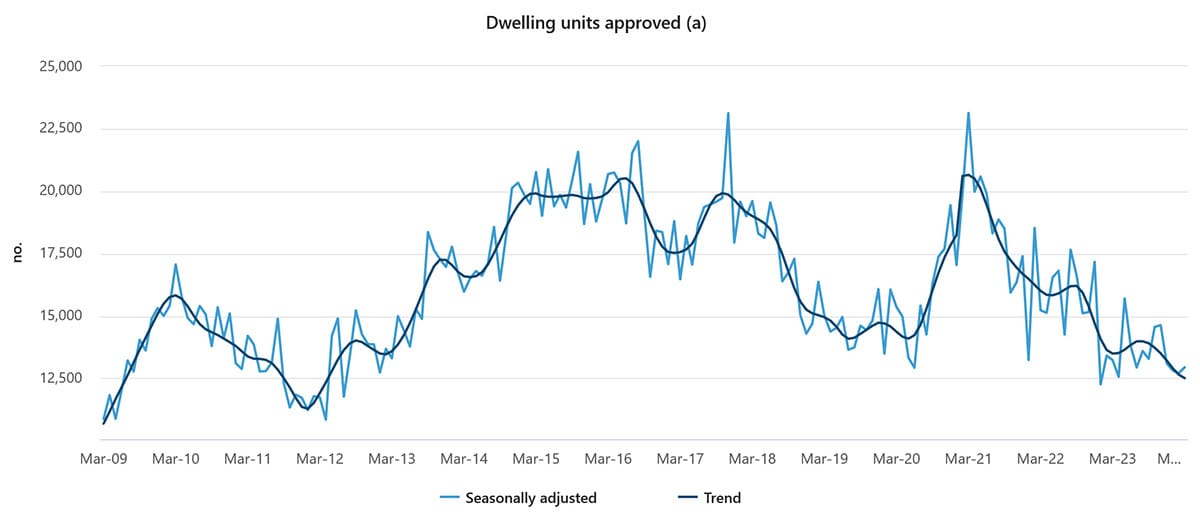

The good news is that housing construction costs now appear to be growing only a little faster than their long-run trend. The bad news is that the level change has flowed through to housing and rental prices, and looks like it will continue to do so at a faster rate than it has historically. Houses are still very expensive to build at current prices, with approvals now back at 2012 levels. There's just not much profit in building houses right now.

So, while zoning reforms and cash to build affordable housing will help, to resolve the current crisis requires addressing the immediate issue of construction costs. A key part of that is having more people to do the work and getting inflation down, especially for materials used in construction.

One way the government could achieve that is by telling its union buddies to cool it on the industrial action:

"According to DP World, the protected industrial action has pushed delivery times of some essential items behind by at least two to eight weeks, with a backlog of more than 50,000 containers sitting at Australian ports."

Chinese shipping companies cancelled one-fifth of their container services to Australia in January this year. From where do more than 60% of our home building materials come? China. We should be doing everything we can to avoid supply shocks, not inviting them unnecessarily (the relevant Minister, Tony Burke, has the power to intervene, as happened during the 1998 waterfront dispute).

The government could also add skilled construction workers to its visa fast track system, alleviating some of the immediate capacity constraints in the sector and boosting the ratio of construction workers in the economy. It could try to incentivise states to relax some of the licensing arrangements for workers in the building and construction sector, which "have become more stringent across most jurisdictions" over the past several years, with many reforms "characterised by poor assessment of health and safety risks and inadequate consideration of whether alternative regulation already addresses the problem".

Yes, the extra 20,000 fee-free TAFE places for tradies and construction workers in the Budget might help train up new workers in the medium-term, but it's a drop in the bucket for an industry of nearly 1.5 million, especially as many would have entered the industry absent the subsidy anyway.

The fact is that without more affordable materials and workers to actually build the damn things, the government has a snowball's chance in hell of reaching its 2030 housing targets.

Unfortunately, doing most of what I've suggested above would royally piss off powerful factions within Labor, so I don't expect it to happen. Instead, we'll get more money thrown at the problem, which will at best reallocate some new housing away from market-rate construction towards additional social and affordable homes. That might be something we, as a society, want. But it won't bring more materials through our ports, and it won't give us more skilled construction workers, so it won't do anything to get more houses built.

But it could be much, much worse

The government's solutions don't look like they'll fix the crisis, but at least they're not making it worse. As I said at the start, there are always plenty of bad ideas floating around, and that's just as true for housing as it is for social media.

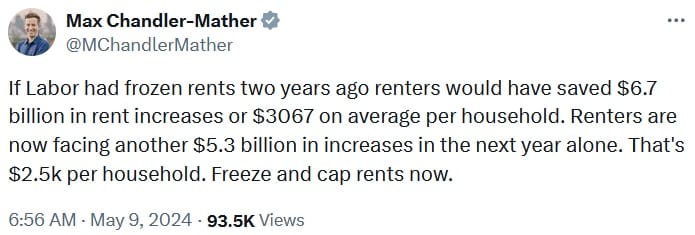

Perhaps the most reckless member of the Club of Bad Ideas is Greens housing spokesperson Max Chandler-Mather, who wants to freeze rents despite the considerable evidence that it creates large "adverse effects affecting the whole society".

He has a whole page dedicated to freezing rents, in which he claims "greedy and opportunistic behaviour from landlords has been a significant driver of the homelessness crisis we see daily in the news".

Now, many of Australia's 2.9 million landlords may well be greedy and opportunistic. But they didn't all get greedy at the same time. Nor did they all suddenly get together at the annual landlord gathering and agree that now was the opportune time to start screwing renters over. No, what happened was the cost to maintain and build housing increased, as did the demand for rental housing (higher incomes, smaller household sizes, people renting while building, rebound migration), so barring a sudden supply response, rents had to go up as well.

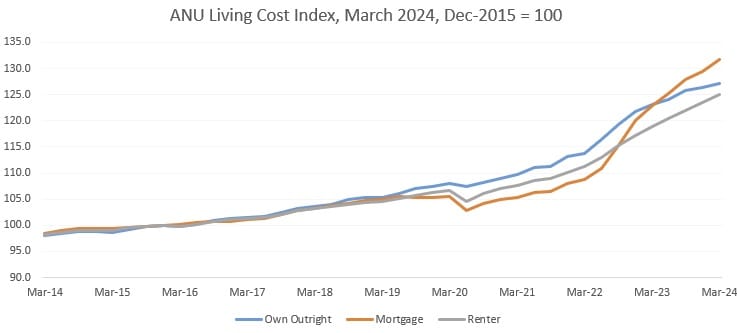

But if Max just took a moment to look at the data, he would see that renters have actually fared better than owners over the past decade, and especially over the past few years. Life has been tough for everyone!

According to ANU's Ben Phillips, who updates the index, that's because rents have increased broadly in-line with overall prices (even before Commonwealth rent assistance), while homeowners have been stung by higher interest payments and large cost increases in the things renters don't have to pay for, such as repairs and maintenance. That's consistent with research released by the RBA late last year, which found that unlike households with a mortgage, the spare cash flow of renters had actually "risen a little as high inflation and rising rents have been more than offset by growth in income".

Thankfully, Max's ideas don't appear to have much traction beyond the Greens. I just hope that it stays that way, because all it would take is someone like Peter Malinauskas to drink Max's Kool-Aid to absolutely devastate the housing market in a state.

Member discussion