Quotas are always the wrong option

The title of this post is deliberately provocative. I don't actually believe that quotas are always the wrong option. For example, in fisheries when there's "uncertainty about the availability of fish or fish price", a quota might be preferable to fees, at least until that discovery process has taken place (although probably not).

But when it comes to policy, there are very few situations where quotas are the right option, relative to the alternatives. Yet that's exactly what our government is proposing to implement to limit international student numbers:

"The Australian government is currently holding consultations over a plan to cap the number of international students that domestic universities can accept. The policy is intended to address community concerns over high post-Covid migration numbers which are aggravating a national housing shortage, as well as some questions over the quality of service provided by Australia's tertiary institutions."

The bill is currently subject to a Senate inquiry, which is due to table its report in around two weeks. But in its current form, it would give the relevant minister (Education) the power to put:

- a limit on the number of overseas students that may be enrolled in all courses provided by a provider in a year; and

- a limit on the number of overseas students that may be enrolled in a particular course provided by a provider in a year.

Now, sure, the minister may never choose to exercise that power. It could be something like the Treasurer's power to overrule the board of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA): the power is there but using it means we're either in a deep crisis or are about to be. It's there purely to keep the universities in check, sending a message along the lines of 'don't go getting yourselves too dependent on international students or we'll whack you with this big stick'!

But somehow I doubt it. At a recent education summit, minister Jason Clare stopped short of disclosing what he considered "too many international students", but he certainly didn't deny that the government had a number in mind. In fact, he said that the new bill is designed to replace Ministerial Direction 107, which is what the government is currently using to throttle visa approval times based on a university's "risk".

So, assuming the bill clears the Senate, then an international student quota looks to be in our future. But there is a better way!

Use fees, not quotas

The government doesn't need the power to restrict total international student numbers, let alone how many attend individual university courses – talk about micro-managing! – because it already has, and has recently used, the most powerful tool available: prices!

"The Albanese government has more than doubled the international student visa application fee from $710 to $1,600 in the latest measure to reduce arrivals to Australia.

The government announced the move on Monday, confirming pre-budget speculation in the tertiary education sector that fee hikes will be used in addition to the international student cap as a means to reduce net migration."

Higher fees will do the job without a quota. Done properly, they can render a quota useless: all you have to do is set the fee high enough to reduce demand to whatever you consider "appropriate", and the number of applications will fall to that level. The government then collects a bit of extra revenue it can use to offset some of what the public perceives to be the worst consequences of international students, which mostly seems to be housing-related, and we can all get on with our lives.

But there are even more benefits of using a fee over a quota. The first is it's more equitable: our universities earn rents by attracting international students and charging them significantly more than domestic students. By increasing the fee for international students, the government can tax away some of those rents and ensure a more equitable distribution of them. Perhaps vice Chancellors will have to take a bit of a pay cut, and universities will have to scale back some of their more ambitious want-to-haves, rather than need-to-haves to educate society, but everyone else benefits.

The second is it's more efficient. Ideally fees would be set dynamically, by semester, to balance the desired supply of international students with the demand for them. If we're getting too many students wanting to go to the bigger, wealthier inner-city universities, then charge a higher fee to go there, effectively taxing away some of their unearned rents and encouraging students to attend campuses where they will have less of an impact.

Regulating the intake of international students by price rather than quantity compresses all the necessary information needed for both students and universities to make efficient, decentralised decisions without a government going around and telling them 'oh hold on a moment, 100 students in Econ101 at Sydney Uni is the appropriate number, not 150'. How the Education minister could possibly know the right amount of students to allocate across our 42 universities and thousands of courses is beyond me.

The third and final reason a fee is better than a quota is that with a quota, the difference between supply and demand can grow unbound until it creates all sort of perverse incentives, and rewards the students and universities that it probably shouldn't be. A fee that attracts exactly as many students as a quota is a direct transfer from those foreign students to the government. But a quota creates the incentive for foreigners to establish cartels, controlling who gets the prized, well-below willingness to pay places at Australian universities.

And let me tell you, under that model we won't be getting the best and brightest but a legion of princelings, whose politically powerful parents will have the incentive to capture the application process in their country.

International students boost our economy

International students are also good for the Australian economy, which is why it's important to have an efficient visa allocation system regulated by prices, not quotas. We should want to maximise the number of students up to the point where it's politically or socially unsustainable (e.g. where the perceived costs they impose on, say, housing and congestion are greater than their fiscal benefits).

But some don't think students bring any benefits. For example, journalist Alan Kohler recently claimed that students are an "import" and therefore do not contribute to the Australian economy:

"Education is described as Australia's largest non-mineral export. $48 billion a year, fourth largest export after iron ore, coal and natural gas. However, it's actually dodgy numbers. What the ABS [Australian Bureau of Statistics] does in order to achieve that $48 billion is that they just count or estimate, it's not actually counted, it's estimated – they estimate everything that foreign students spend in Australia.

It's their tuition fees plus all of their spending to live here, rent, food and so on. The trouble with that is that a lot of the money is actually earned here as you say. I mean they get a job, right? So, it's not money that's brought in and in fact if you look at the data they seem to be sending money out, repatriating more money than they bring in. The foreign education should be called an import not an export."

It's a shame that the national accounts identity can be so confusing to people. From the perspective of gross domestic product (GDP), it's largely irrelevant how students earn the money they spend here. GDP, which counts imports and exports, measures final domestic production. And despite being in the equation, imports aren't really part of GDP at all; they're an offset so that we don't double-count final production in the Consumption + Investment + Government + eXport components.

When the ABS is estimating the impact of international students on GDP, they don't include their consumption of goods and services in "C" because they're deemed to be non-residents. But they still consume, and that has to be measured somewhere. Given that their consumption represents the purchase of many final goods and services produced in Australia – education, housing, food, etc. – most of it goes into "eXports":

GDP = C + I + G + ((X − M))

International students cannot be an import, as that would imply that their consumption of Australian goods and services has already been counted in "C", "I" or "G", which isn't true.

Essentially, Kohler has been bamboozled by the deceptively-simple GDP accounting identity, a trap many fall into (most notably Donald Trump). But as the US Fed's Scott Wolla explains, you need to pay attention to what GDP does and doesn't measure:

"GDP measures domestic production of final goods and services. The expenditure approach calculates GDP using total spending on domestic goods; but the equation, as stated, can lead to a misunderstanding of how imports affect GDP. More specifically, the expenditure equation seems to imply that imports reduce economic output.

...

This essay explains that the imports variable (M) corrects for the value of imports that have already been counted as personal consumption (C), gross private investment (I), or government purchases (G). And remember, the purchase of domestic goods and services should increase GDP, but the purchase of imported goods and services should have no direct impact on GDP."

Unless international students were coming here and spending everything they had on overseas-produced goods and services, or sent it all back as remittances – which seems completely implausible given that a large part of what they do here is buying education being taught at an Australian university, living in an Australian house, eating Australian-made food – then they add to exports, increase GDP and are an important part of our economy.

A solution looking for a problem

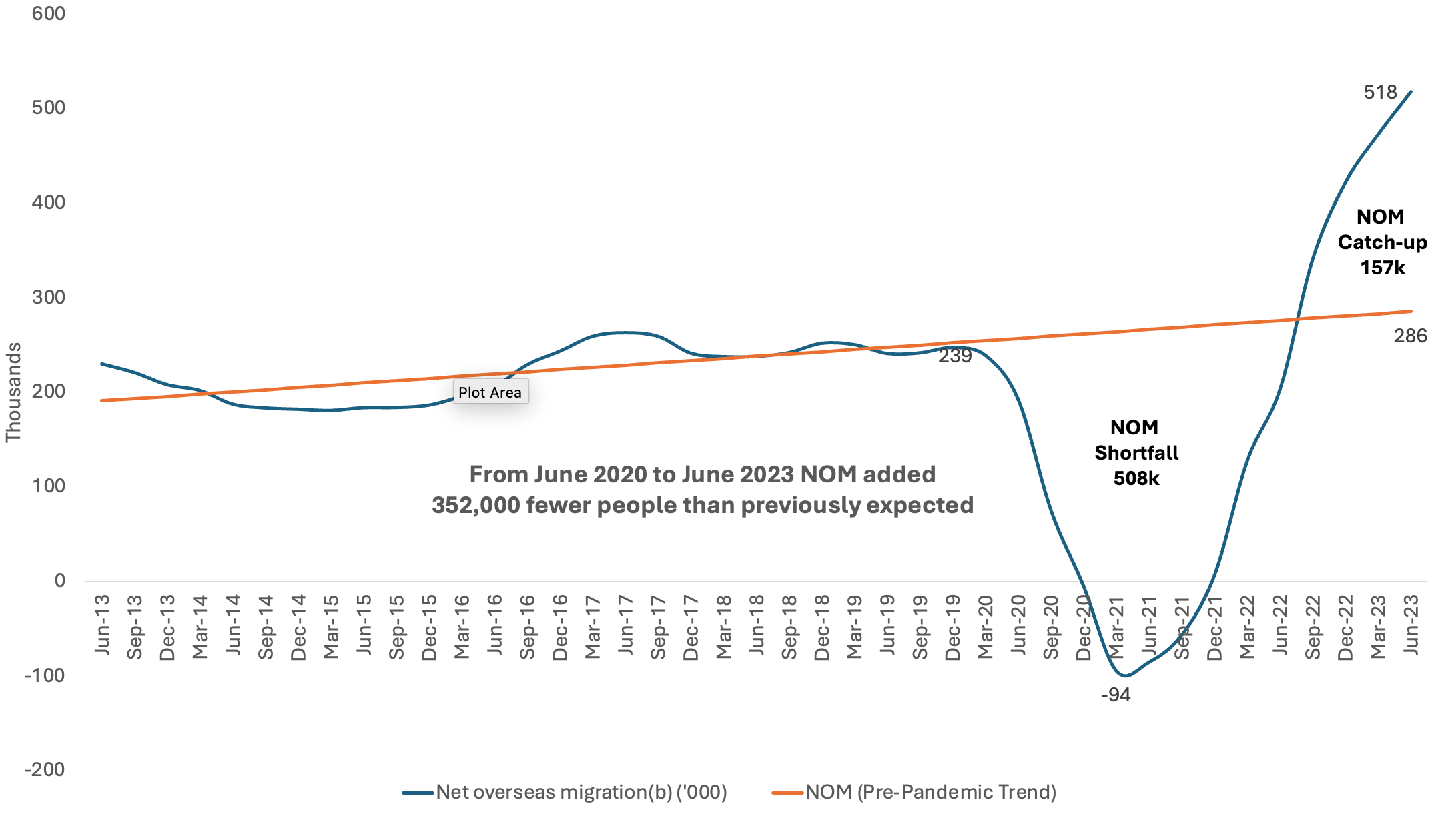

There's no doubt that international student numbers have surged in recent years, putting strains on the structurally-constrained parts of our economy, e.g. housing and infrastructure, that had been neglected for far too long. But it's also largely self-correcting, because the surge is the result of catch-up growth from having our borders closed for a couple of years. As ANU's Alan Gamlen has documented, Australia's population may have been even larger today if the pandemic had never happened; pundits just wouldn't have noticed because we never would have had the high rates of growth we saw when the border reopened.

For me, I'm most worried about the incentives and the consequences of the bill. If Australia adopts a quota system for students, the incentive for politicians to fix the structural problems in the economy diminish because the true cost of that quota is largely hidden from sight.

Alternatively, if the fee on international student visas were properly used to regulate numbers, there would be a strong incentive for revenue-hungry politicians to bring more students in without triggering a backlash, e.g. by ensuring there's sufficient student accommodation available. Not only would that improve economic growth (more exports), but the extra fees would reduce the tax burden on us natives. The higher fees could also be expected to raise the quality of the students accepted as they would also have more skin in the game, unlike in a 'first come, first serve' or lottery quota system.

I can't help but feel the proposed bill is a populist solution looking for a problem. The government has already intervened to prevent non-genuine students from getting visas, and raised student visa fees. When combined with an inevitable reversal of the post-lockdown surge, those actions should be enough take the heat out of student numbers in the coming months and years.

So, by the time any quota comes into play, the international student 'problem' will probably have resolved itself; if anything, the risk then flips to too few students, cutting off a big export at the same time as key commodity prices descend from their lofty heights and our economy, burdened as it is by restrictive interest rates, really starts to slow down.

Member discussion