Russia's Black Death

I've written a few posts about countries that are either relatively similar to Australia (e.g. New Zealand, Canada) or are major trading partners (e.g. China, Japan). But today I'm going to go off the deep end a bit and take a look at Russia.

Why Russia? Well, the FT recently published a feature article titled Russia's surprising consumer spending boom, which it claimed was "a radically different outcome than economists were expecting at the onset of war".

At first glance, that view is understandable: after invading Ukraine, Western nations pummelled Russia with trade sanctions, including freezing 70% of the country's financial assets.

Then there's the toll of the war itself. While estimates vary wildly, since it invaded Ukraine Russia may have lost something like 150,000 lives, with at least 200,000 wounded. Perhaps up to another million Russians have fled the country since the start of the war. Given that almost all of those people were probably of working age – i.e. young men fighting or fleeing conscription – and you're looking at a rapid loss of around 2% of Russia's labour force.

Put it all together and it's perfectly reasonable to be asking how on earth is Russian spending booming when they've lost that much wealth and that many consumers? But there's a fairly straightforward answer.

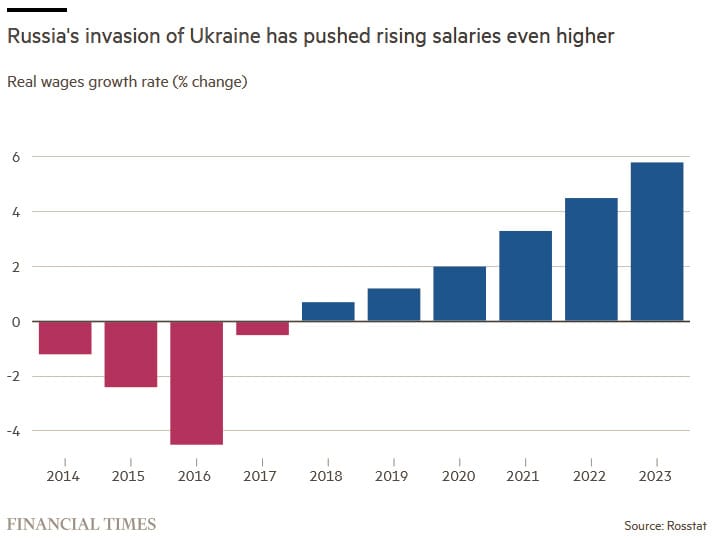

Basically, Russia did the invading, so the amount of physical stuff (capital) in the country is largely unchanged. When Russia lost a bunch of working-aged people, real wages rose because there was suddenly a lot less labour for that stock of capital. With more capital per worker, labour productivity rose and real wages followed as competition for the remaining workers heated up:

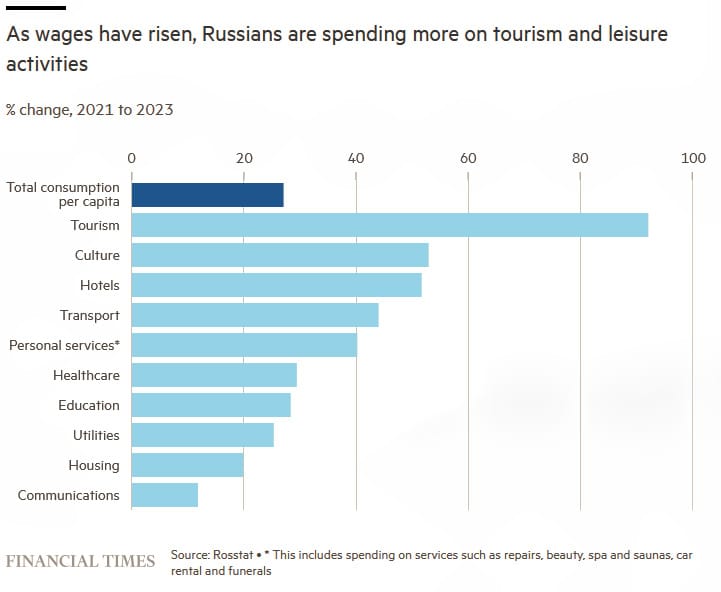

Russia's people now have greater purchasing power than they did before the war, so they want to buy more stuff. However, given that the most desirable goods are harder to come by because of sanctions and the general economic repression to support the war effort (production shifting from consumer goods to military goods), they're also consuming more leisure:

Disasters and wars can raise wages

This effect shouldn't be surprising and has been observed throughout history, with the most extreme example being when the Black Death ravaged Europe. According to the excellent book How the World Became Rich (2022) by Mark Koyama and Jared Rubin, the plague initially caused an economic crisis where trade "collapsed and real wages fell as food was left rotting in the fields and crops were not harvested".

But while it was "undoubtedly awful for the people who lived through" it, fewer mouths to feed saw per capita income "rise for at least a few generations":

"Pamuk (2007, p. 292) finds that the Black Death caused urban real wages to rise by as much as 100% in the decades after 1350. They remained above their earlier levels until late in the 16th century. This was true not only in Western Europe and the western half of the Mediterranean but also around the eastern Mediterranean.

Land use also changed. Marginal lands were abandoned and landowners shifted away from arable farming (which was relatively labour-intensive) towards pastoral farming (which was more land-intensive). To paraphrase Sir Thomas More (1516/1997), sheep devoured men. Jedwab, Johnson, and Koyama (2019) find evidence for substantial geographic mobility in the wake of the plague as people moved in search of better economic opportunities."

The Black Death also triggered institutional change, perhaps even kicking off the rise of agrarian capitalism, because serfdom ended as the "shock of the plague simply made it impossible for landlords to maintain or reinstate servile institutions and impose feudal dues on recalcitrant peasants".

Of course, the Black Death – which wiped out up to half the European population – was much more severe than the losses Russia has taken following its invasion of Ukraine. But the dynamic is similar: economic crisis followed by a temporary increase in real wages at a rate faster than real GDP per capita growth.

So, it shouldn't really be a surprise that a similar effect hit Russia, admittedly at a much smaller scale: in 2022, Russia's GDP contracted more than 2% (it invaded Ukraine in February of that year) and its real wages plunged before staging a rebound thanks to the rapid expansion of the country's "military-industrial complex" and loss of people.

But in all the historical examples, because there was never a sustained increase in productivity, just a one-off level change – fewer people with the same capital stock raises labour productivity – real wages eventually fell again. The same is likely to happen in Russia as its capital stock is depleted by government-directed military spending:

According to Manfried Rauchensteiner's book The First World War and the End of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1914-1918 (2014), the Austrian-Hungarian Empire did just that during World War I. But the state's demand for workers and rising real wages came at the expense of other industries:

"In order to obtain the required manpower, the armaments manufacturers began to pay their workers higher wages. This had an almost instant impact on other businesses and firms, which could not compete with the wages of the armaments industry and were thus unable to find any workers. In the Wöllersdorf armaments factory, for example, the number of male workers increased five-fold from August to the end of December 1914, but a construction firm that was supposed to build new aircraft engine hangars had to appeal to the War Ministry because it could no longer find any workers."

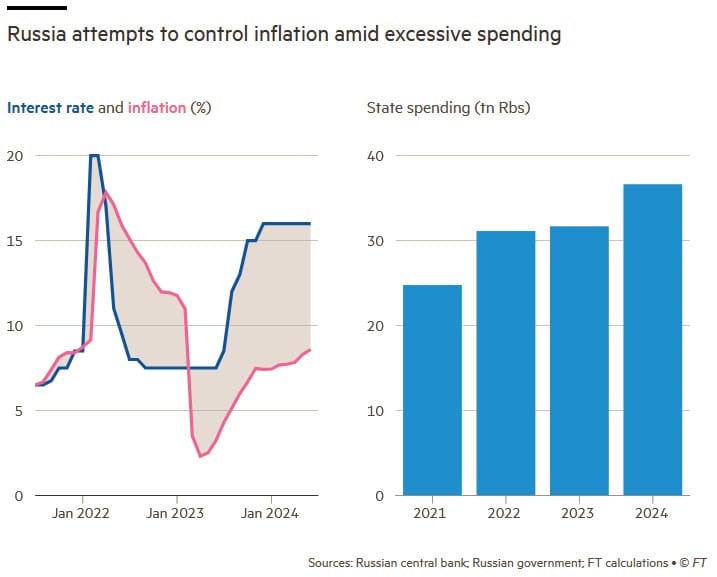

Essentially, the rest of the Russian economy is being hollowed out by a state that's now spending nearly twice as much as it was in 2018, with defence spending alone triple what it was just three years ago. A war economy, where so much is being built to destroy or be destroyed, does not help to increase a nation's capital stock. It might temporarily boost GDP and real wages, but because it's not efficiently expanding the country's productive capacity, it's basically like a Future Made in Australia on steroids: in the long run, capital will be consumed faster than it's replaced, economic growth will slow, and wages and consumption will fall.

Unproductive but resilient

After reading his own obituary, Mark Twain famously replied by saying "the report of my death was an exaggeration".

A similar quip could be applied to Russia; people have been speculating that Russia would be forced into a peace deal, or would simply collapse for... well, ever since it invaded Ukraine.

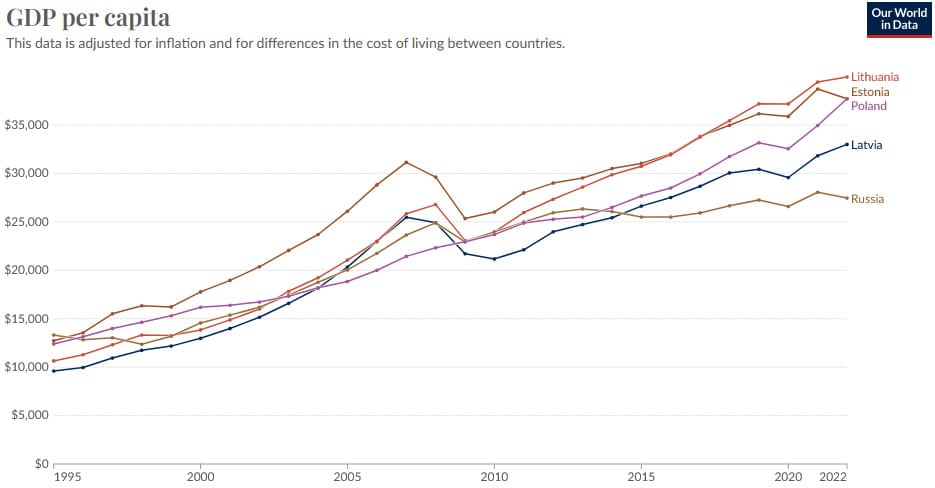

But the Russians are used to being repressed. In fact, ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia's economy has struggled. Not as much as it was struggling prior to the collapse, to be sure, but it has clearly underperformed not only Western nations but also former Eastern bloc countries such as the Baltic states. Since 2015, Poland has absolutely blown it out of the water:

Russia has barely grown at all since 2008, which is roughly when oil prices collapsed and Vladimir Putin started the country on the road towards self-sufficiency:

"This most recent drive toward self-sufficiency and rebalancing can be traced to the 2009 document 'Russia's National Security Strategy to 2020,' in which the Kremlin laid out its intentions for the coming decade. Among its directives were to increase food security; foster competitive domestic industries in pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, computer technologies, electronics and programming; and de-emphasise the importance of the raw materials export model. To put these directives in context, it is necessary to understand something of the development of the Russian economy, which as in all cases is a product of its challenging geography."

What Putin kicked off could also be called import substitution industrial policy on a grand scale. But unlike the politicians and academics who pushed for import substitution as a path to growth, Putin was probably fully aware of the trade-off; that he was repressing consumers to give Russia more geopolitical independence:

"Finally, and more broadly, Russia's increased self-sufficiency in agriculture will give it more freedom in international affairs. When a country is reliant on food imports, it becomes more susceptible to sanctions pressures. A more self-sufficient country by comparison can take more risks without fear of reprisal. In the short term, then, increased self-sufficiency will leave Russia poorer, but also more independent."

So, Russia's weakness in peacetime is also a strength in wartime. It has a large domestically-driven economy with relatively limited reliance on foreign trade, other than a huge amount of oil exports (some ~11% of global supply).

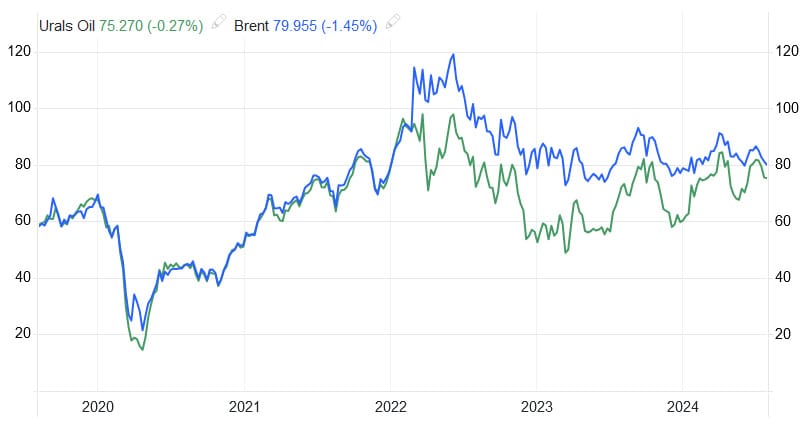

Yet despite Western sanctions, it has had no trouble selling that oil and using the proceeds to replenish its stock of foreign reserves and finance its ongoing war effort. It turns out that oil is very fungible and Russia simply rerouted its oil from Europe to the East:

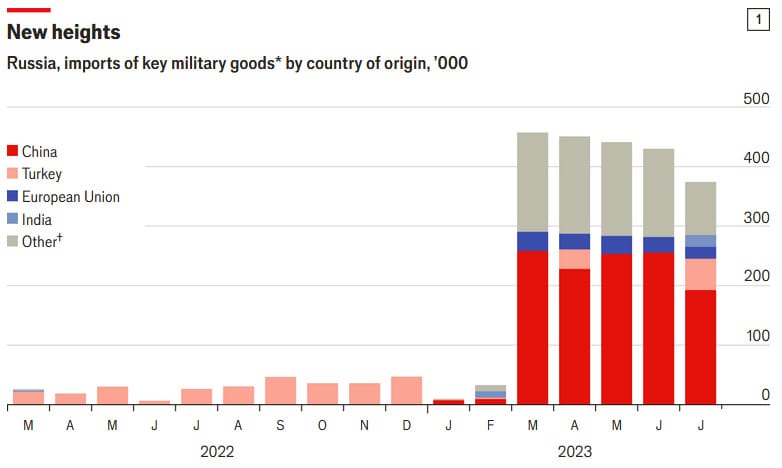

It's a similar story for military components, machinery and other goods that it can't manufacture in Russia:

As for technology? Well, it's just stealing that:

"Shell companies at that address have acquired millions of restricted chips and sensors for military technology companies in Russia, many of which have been placed under sanctions by the US government, according to an examination by The New York Times."

How has Russia managed to so effectively bypass santions? Well, it's very profitable for countries like China and India to buy Russian oil, 'process' it, and ship it straight back to Europe. And when there's a will, there's a way:

"European countries have led the enforcement of sanctions on Russia, but remain connected to Russian oil. In 2023 they imported roughly 225,000 barrels per day (b/d) of Indian petrol and diesel products, up from an average of 120,000 b/d in the previous five years, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). These exports have boosted India's trade balance and are another illustration of India's growing clout in the market. In 2023 oil-related exports were worth $85bn, around 60% more than in 2021."

When sanctions are imposed trade doesn't stop but is rerouted, which really shouldn't have surprised anyone. I mean, it happened in Australia when China 'blacklisted' our coal and barley. China still needed those goods, so it purchased them from elsewhere and Australian coal and barley replaced whomever was buying that, or in the case of barley, planted more canola instead.

The same happened with Russia: when sanctions were imposed, there were still plenty of countries that were more than happy to either buy Russian goods directly, or via an opaque network of 'grey trade', given the considerable discounts on offer. And today, the spot where Russia was most vulnerable prior to the war – oil exports – may no longer be soft. In fact, the global oil market has adapted so well that the spread between Russian Urals and Brent crude has almost completely closed:

Argus notes that the shift to the East has been so strong that it's not sure Brent crude will even be a reliable pricing indicator in Asia going forward:

"Prior to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Urals crude was the key export grade loaded onto vessels in the Baltic and Black seas for short-haul voyages to northwest Europe and the Mediterranean region, and piped to inland refineries from Leipzig to Budapest. But now, conflict and geopolitics, rather than economics, have forced Urals eastward.

In benchmarking terms, Urals has moved from the Brent sphere into the Dubai sphere — from a light sweet European benchmark, to a medium sour Middle East benchmark, which better aligns with its own properties.

...

With Urals now lending its weight to Dubai, rather than Brent, the division of the crude market into two distinct spheres of influence appears to be hardening. Whichever benchmark ultimately succeeds in Asia, it will be measured against WTI at the global level."

With its supply chains effectively secured and a dwindling Ukrainian resistance – especially if Donald Trump wins in November and cuts off a key source of funding – there's no reason why Russia can't continue this war indefinitely.

Bad news for the World

Economically speaking, Russia will stagnate. It now has something resembling to the opposite of a dynamic, market-based economy, and is as close as it has been since the Soviet Union collapsed to the North Korean or Venezuelan end of the economic spectrum. Its people will be considerably worse off because of the invasion of Ukraine and Putin's push towards self-sufficiency.

But Russia's capability to be a geopolitically independent, warmongering nation is stronger than ever. And if you're Putin, you don't care about the people of Russia, so long as you can maintain power and give them their bread and circuses.

You see, Putin has a grand plan; he wants to 'unify' the Russian empire to an arbitrary point in time prior to World War I. He has made no secret of that goal, and was highly critical of Ukraine prior to invading it:

"[M]odern Ukraine is entirely the product of the Soviet era. We know and remember well that it was shaped – for a significant part – on the lands of historical Russia.

...

In essence, Ukraine's ruling circles decided to justify their country's independence through the denial of its past, however, except for border issues. They began to mythologise and rewrite history, edit out everything that united us, and refer to the period when Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union as an occupation. The common tragedy of collectivisation and famine of the early 1930s was portrayed as the genocide of the Ukrainian people."

Putin's narrative is incorrect, but being wrong has never stopped a tyrant before and it won't this time, either. In Putin's mind, he's a visionary and the people will thank him later.

Unfortunately for the World, a poorer but largely self-sufficient Russia (so long as China and India are complicit) is still dangerous. Russia and its allies will continue to be a geopolitical threat so long as Putin is alive, even if its economic influence wanes.

Member discussion