Should we be more like Denmark?

Monday's free post looked at the housing model in Vienna, Austria, concluding that it's probably not something we could easily transplant into Australia, even if we wanted to. But it got me thinking – what about other countries? Specifically, countries that also rely on market-based housing and might be more applicable to Australia than a small, homogeneous city in Austria. How are their markets structured?

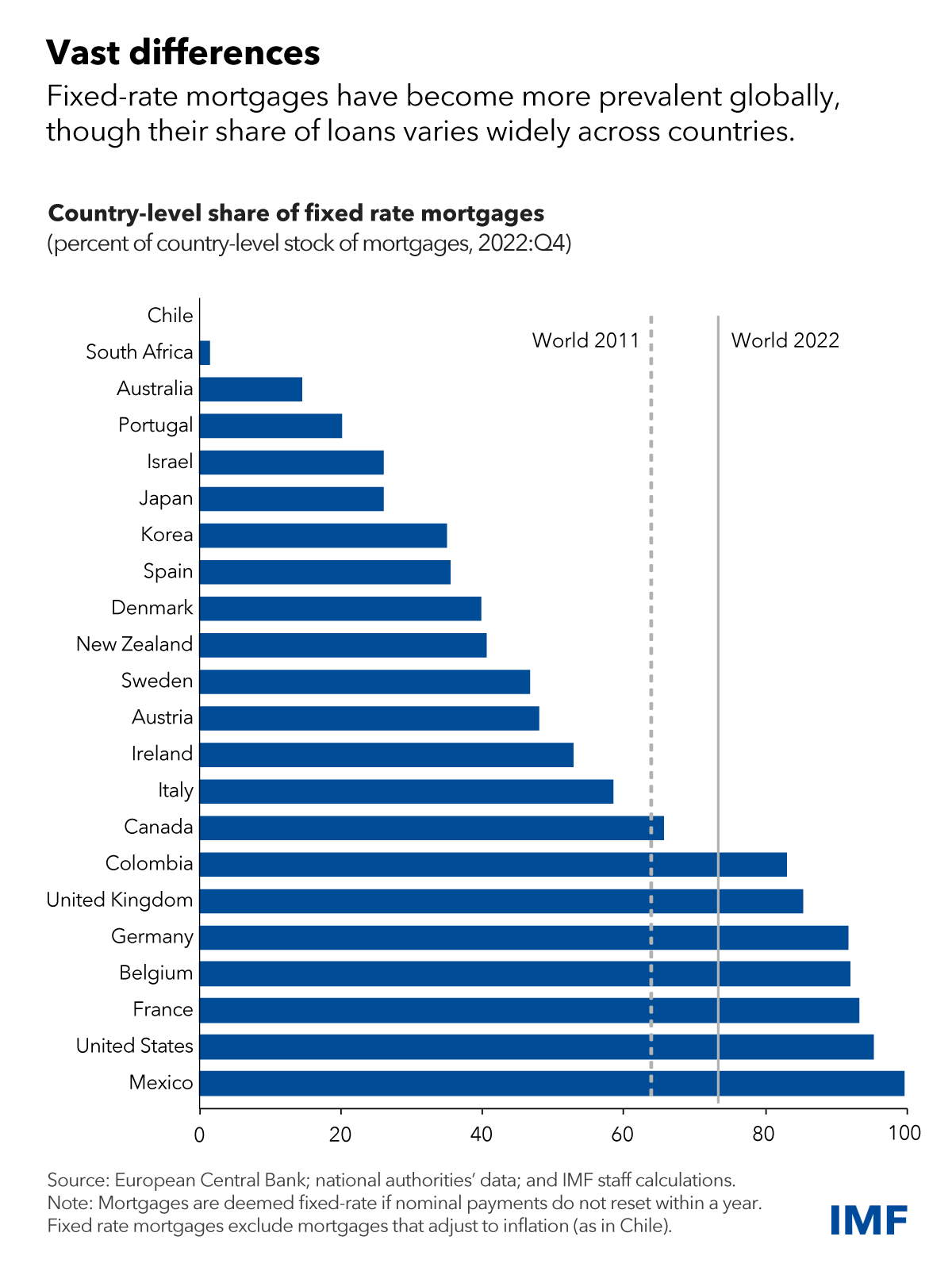

Now, for market-based insights one can't help but start with the US, given its enormous size. The US can certainly be a quirky place, and it turns out that its housing industry is no exception. Instead of borrowing at variable rates like almost everyone does in Australia, when you take out a mortgage in the US you're generally locking in the rate for up to 30 years. And it's not alone; some European countries – specifically France – also lock in mortgage rates for an average of 20 years. The IMF recently provided a helpful graphic showing the "vast differences" between countries, with Australia down at the variable extreme and the US at the the fixed extreme.

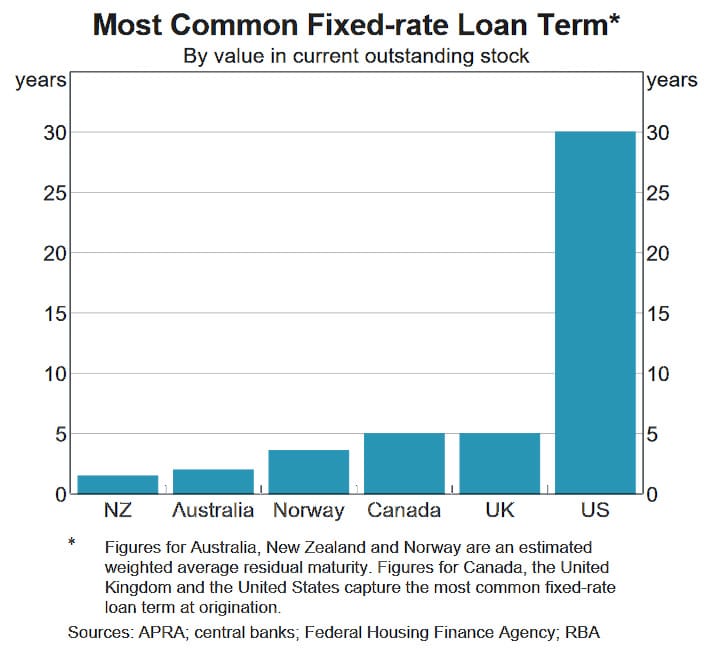

What the chart doesn't show are terms. For example, the UK has a relatively large share of fixed mortgages but they're mostly for fewer than 5 years, so in practice they're not all that dissimilar to Australia.

Now, banks borrow short and lend long – how on Earth do they manage the enormous maturity mismatch risk that a 30-year fixed-dominated model entails, and could we implement something similar in Australia?

The French model

In France, covered bonds with mortgages used as collateral are the go-to method (it's the largest covered bond-issuing country in Europe). The credit risk remains with the originator, but the the industry also self-insures them (Crédit Logement) so that the system as a whole can absorb any failures. The fact that banks are still on the hook gives them the "incentive to manage it prudently", as opposed to the securitisation model used in the US, which allows the risk to be passed on.

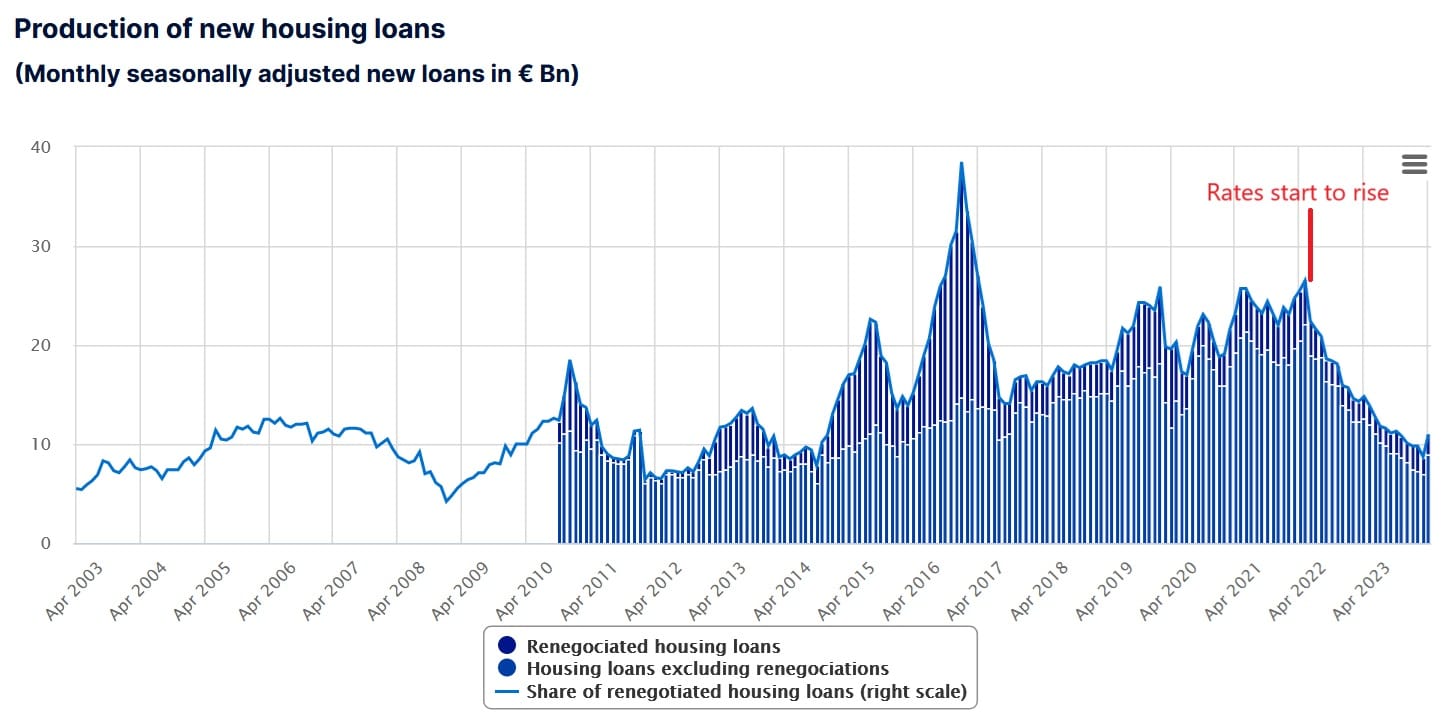

There are downsides to such a relatively risk-averse model. For example, when rates rise, loans issued tend to fall not because consumers don't want to borrow but because the banks can't make money on new mortgages: fixed-rate mortgages are tied to the market in government debt, and there are usury rates (maximum interest rates) set by the Bank of France that tend to trail market rates.

So, good for some, but if you're trying to get onto the property ladder during a time of rising rates, you might not even be able to find a lender willing to take you on.

The American model

In the US, the simple answer to 'how do they do it?' is that the banks don't manage the maturity mismatch risk at all; a legacy of the Great Depression, most US bank-issued mortgages are sold to government entities (e.g. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), which then guarantee it against default, package it up with a bunch of other mortgages into what's known as a mortgage-backed security, and sell it on to investors (or the US Federal Reserve if no buyers can be found, as was the case during the Great Recession).

By government entities assuming most of the risk, the downsides of the French model aren't as apparent; banks are still willing to lend when rates rise. But there are costs of putting all the risk of 30-year, fixed rate mortgages (FRM) onto taxpayers:

"The interest rate and prepayment risk in the FRM are costly and difficult for investors to manage. There is a premium for both the long-term and the prepayment options that are paid by all users of the mortgage. The FRM causes instability in the mortgage market through periodic refinancing waves. The FRM can create negative equity in an environment of falling house prices. And the taxpayers are on the hook for hundreds of billions of dollars in losses backing the credit risk guarantees provided by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to support securities backed by the FRM."

Another consequence of markets where FRMs are the norm and the rate cannot be transferred are the so-called 'golden handcuffs':

"Many Americans who want to move are trapped in their homes—locked in by low interest rates they can't afford to give up.

These 'golden handcuffs' are keeping the supply of homes for sale unusually low and making the market more competitive and pricey than some forecasters expected."

This is actually a fundamental difference between the US and Australian economies. When our respective central banks tighten monetary policy, many Australians feel the pain directly in their hip pockets, while American mortgage holders are insulated from the direct impact. Sure, depositors benefit, but the ratio of household deposits to liabilities is around 50% in Australia, meaning in aggregate higher mortgage repayment rates are likely to sap far more purchasing power out of the economy than is put back in via higher deposit rates.

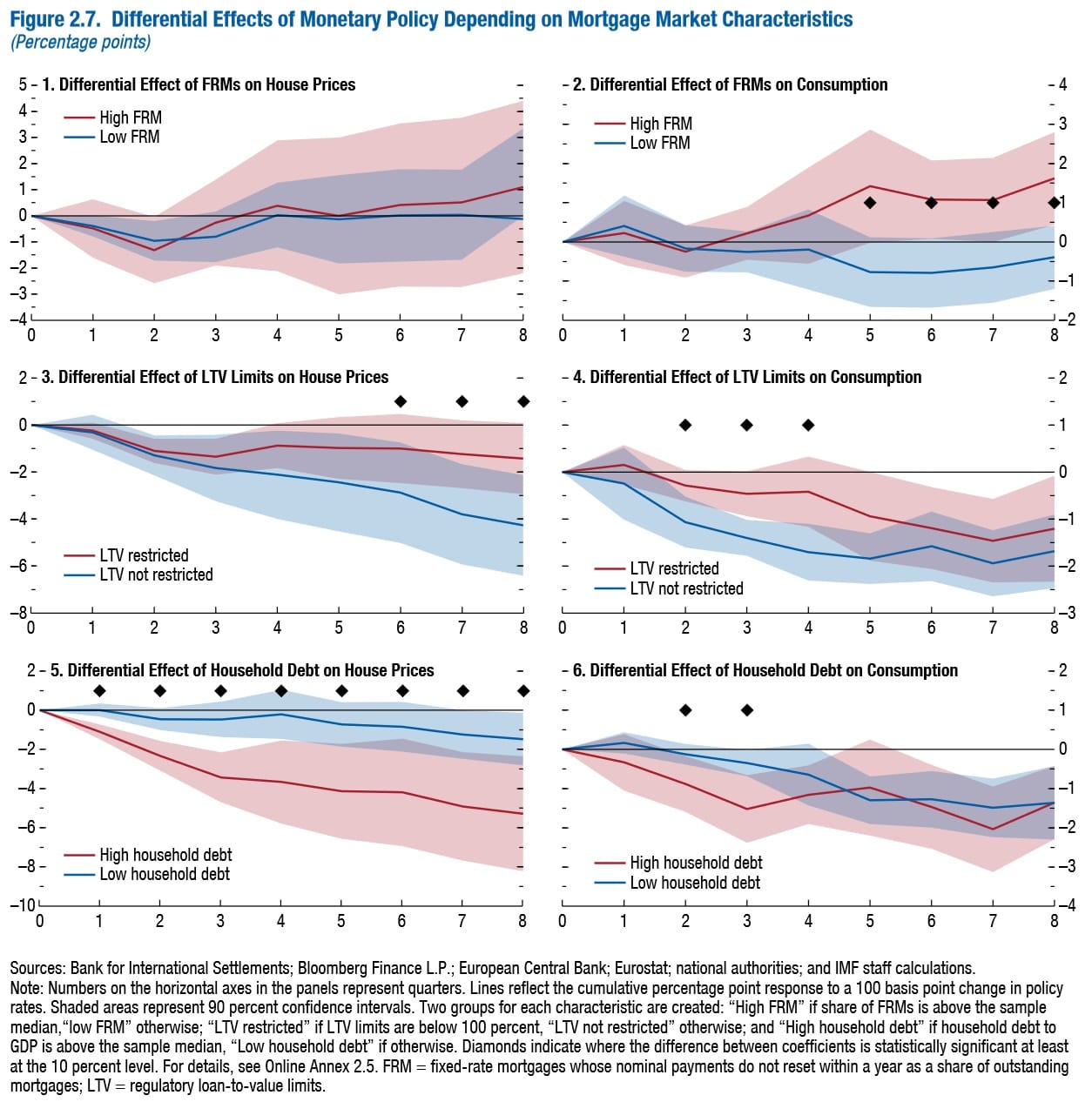

The Australian market also continues to clear, avoiding the lock-in that can occur in France and the US. A recent report by the IMF found that such mortgage market differences may also impact how effective monetary policy can be at reducing aggregate demand (some caution is required: a 2022 study by the Dallas Fed looking at Canada, which is also dominated by variable rate mortgages and relatively short-term FRMs, did not find any "durable spending decreases when mortgage rates increase").

So, while many American home-owners are able to dodge the impact of higher interest rates on mortgage repayments due to their fixed rates, they certainly feel it elsewhere, namely in the form of decreased mobility: to move to a better job in another location, a household with a juicy 30-year, 2.6% rate locked in during the pandemic would have to give it up for something closer to 7.0% today.

Add stamp duty and other fees onto that and you get a potentially significant economic allocation issue caused by very large transaction costs. Not only are people with mortgages 'handcuffed', but even those without a fixed mortgage are worse off: housing isn't being freed up for people looking to move in the other direction. Work by the Federal Housing Finance Agency earlier this year suggested that:

"[F]or every percentage point that market mortgage rates exceed the origination interest rate, the probability of sale is decreased by 18.1%. This mortgage rate lock-in led to a 57% reduction in home sales with fixed-rate mortgages in 2023Q4 and prevented 1.33 million sales between 2022Q2 and 2023Q4.

...

These findings underscore how mortgage rate lock-in restricts mobility, results in people not living in homes they would prefer, inflates prices, and worsens affordability. Certain borrower groups with lower wealth accumulation are less able to strategically time their sales, worsening inequality."

Rather than combating inflation primarily through the monetary transmission mechanism (higher mortgage rates reducing household consumption), as occurs in Australia where variable rates dominate, in the US (and France) monetary policy slows inflation by throwing sand in the gears of economic activity.

While no regime is perfect, compared to the US the Australian model doesn't seem all that bad. But could it be better?

Enter Denmark

If you scroll back to the first chart you'll see that Denmark is roughly in between Australia and the US/France with around 40% of its mortgages fixed for 30 years and the remaining 60% on variable rates. While France also uses covered bonds for many of its mortgages, the main difference between the French and the Danes is that the latter operates on a 'match-funding' principle:

"The balance principle imposes strict matching rules between the assets (e.g., mortgage loans) and the liabilities (e.g., mortgage bonds) of mortgage credit institutions. Each new loan is in principle funded by the issuance of new mortgage bonds of equal size and identical cash flow and maturity characteristics. The proceeds from the sale of the bonds are passed to the borrower and similarly, interest and principal payments are passed directly to investors holding mortgage bonds."

That principle effectively gives Denmark's financial system a natural hedge against moral hazard, interest rates, exchange rates, and prepayment risks; features not seen anywhere else in the world. If a mortgage holder in Denmark wants to move house (say, for a new job) but rates have risen, they're not 'trapped': their mortgage is "assumable, which means sellers can hand off their loans to qualifying buyers", and they could always refinance or buy it back at a reduced rate reflecting present conditions:

"Here's an example in dollars: Let's say the face value of a mortgage, or the amount a homeowner would have to pay to get rid of it, is $500,000. But then interest rates rise by, say, 4 percentage points. In the US, this turn of events would trap many homeowners in their house; they would have to not only pay back the $500,000 but get a new mortgage with higher interest payments. In the Danish model, the same situation could work out in the homeowner's favor. That's because as general interest rates rise, the market value of the covered bonds, and therefore the underlying mortgage, drops. So instead of having to pay back the entire mortgage, the Danish homeowner could go out and buy back matching bonds for, let's say, $400,000. If they sell their home for $700,000, they get to pocket $300,000 instead of only $200,000 (not including pesky fees, of course)."

And it has worked out quite well for them. Established in 1797 after the Great Fire of Copenhagen wiped out a quarter of the city's housing stock, there's no record of a single default since inception. During the 2008 crisis, while Denmark's government guaranteed liquidity for its banks, covered bonds were "explicitly and deliberately not included into the guarantees at any point":

"The strict match pass-through funding principle as implemented in Denmark is thus one way to structure a robust house financing system... covered bonds under the match funding principle were as liquid as government bonds also during the 2008 housing market crash. An important feature of the Danish mortgage system is that it does not rely on government sponsoring and the government is not actively involved in the market in normal times."

So, why hasn't the Danish model spread further? Others have tried to replicate what the Danes have built, but none have succeeded. A 2004 report by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) said it was their "suspicion that there is a temptation to underestimate the institutional investments that have to be made".

There's those pesky institutions again. Denmark has some of the best, and is the least corrupt country in the world. So, we could try to replicate the Danish mortgage model in Australia, but not only would it have to survive the political sausage-making process, but we would also need to consider all the other rules the Danes have in place to ensure their system functions properly and how those rules interact with ours, many of which may be difficult to change.

For all its benefits, it's also not clear that the Danish model is optimal for consumers. Interest rates on fixed mortgages can be high, with many Danes choosing variable rates because the more competitive starting rate makes it easier to get on the property ladder to begin with. Unlike Australia, mortgage interest is tax deductible in Denmark (even for owner-occupiers), providing those on variable loans a buffer against rising interest rates.

In addition, one of the institutions that enables the Danish model is more rigorous lending standards:

"Danish mortgage rules are stricter in other ways that favour the lender: Borrowers are required to put down 20% of the home's price, and foreclosures are speedy thanks to a more creditor-friendly legal system."

It's hard to see such a model working in Australia, given that our governments actively encourage people to take out mortgages with "as little as [a] 2% deposit".

So, as with Vienna's public housing, the answer to whether our mortgage system should be more like Denmark is it's complicated. I think, on balance, something like the Danish model is probably preferable to Australia's – especially as it still lets people choose between fixed and variable rates – but it could also very easily go horribly wrong. Our rules were designed around relatively small deposits and variable rates (or short-term fixed rates), so to get the necessary framework established would inevitably involve a long transition period, 'picking and choosing' bits and pieces, and trying to slot them into our existing regulatory regime. If those pieces don't fit together, then the outcome could be worse than if we did nothing at all.

Member discussion