The federal government won't solve the housing crisis

Lately I've been giving a fair bit of attention to the federal Labor government's attempts at dealing with the housing crisis. That's mostly because it's in government and has actionable policies in the space: a housing target of "one million new well‑located homes over 5 years", a multi-billion dollar "Housing Australia Future Fund", and two pieces of legislation – "Help to Buy" and "Build to Rent" – currently being blocked in the Senate.

The federal Greens also get a regular mention because they effectively hold the balance of power in the Senate, so if Labor wants to get anything done, it has to cut a deal with them. Their policies are important to the extent that they influence Labor's policies.

But the federal Coalition? Not so much, mostly because they haven't really said much. But as the election draws near, the Coalition's plan for housing is starting to become clearer. And so far, it's not encouraging:

"In the lead up to the federal election, which must be held by May 2025, the Coalition is trying to woo aspirational first homebuyers with a policy that allows them to access a portion of their superannuation to use as a deposit."

And:

"The Coalition is considering stripping the prudential regulator of some of its powers to regulate mortgage borrowing, and overhauling credit laws that MPs fear are locking first homebuyers out of the property market.

The opposition launched a Senate inquiry into mortgage regulations in August, fuelled by concerns that rules aimed at reducing the riskiest forms of borrowing had gone too far and made banks too cautious about lending to first homebuyers."

So, demand-side measures. Unless there's something also planned to allow for supply to respond, then these policies will boost housing demand and raise prices. In terms of the distributional impact, owners would benefit, some people's access to housing would improve, but plenty of people – especially those with low super balances for various reasons, such as women who have had a career break – would be pushed out.

As for the potential changes to prudential regulations, if people were struggling to get mortgages then it might make some sense if done right – we obviously would want to avoid a severe relaxation in lending standards, such as the one that led to the US subprime crisis in 2007-08.

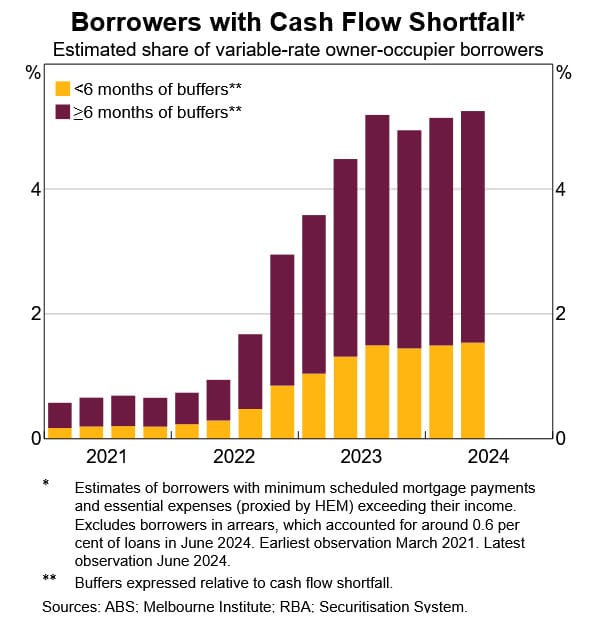

But it's just not clear that Australian lending standards are too tight, given the recent rise in the number of borrowers who are facing cash flow shortfalls:

According to Moody's, delinquency rates have "been rising steadily for the last two years from a historically-low base and were now back up around long-term average levels".

If mortgage delinquency rates are close to the long-term average then it's hard to make the case that lending standards have been tightened "too far", as claimed by the Coalition. The last thing we would want is to loosen lending standards so much as to risk a future financial crisis, given the long-run "scarring" they tend to cause. And for what, to stimulate demand while doing nothing for housing affordability? Really?

Ultimately, there are only a few concrete things a federal government can do to help solve the housing crisis, and none of them have been tried. And from the looks of it neither major party, nor the Greens, appear willing.

We're not building enough

Prices alone don't tell us anything about why housing is less affordable. For example, prices could be rising because households have become wealthier, real interest rates are low, people are willing to spend more on their homes, or because of supply constraints – or most likely, some combination of it all.

Work by the ANU has shown that even after adjusting for quality, "real house prices rose by about 50% between 2003 and 2022", so it's not purely a preference for bigger, nicer homes. It also found no rise in average mortgage payments as a proportion of average household income, so it's not just that we've become wealthier and were willing to put it all into housing: real median incomes are only up about 35% over the same period.

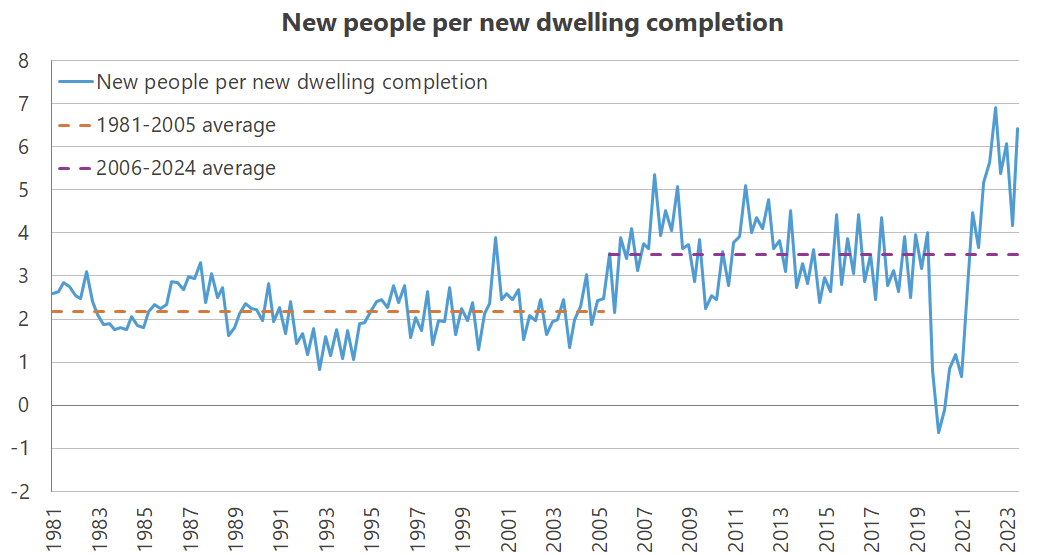

That means other factors explain a lot of the housing affordability problem. And the completions and population data suggest it might be that we just haven't built enough:

It is, of course, a bit more complicated than that; for example, you would have to control the above data for size and quality, changes in the number of people per dwelling over time, and whether those people were children or adults.

But the basic point is that from the early 2000's, housing construction started to lag population growth. Add in the fact that the best jobs are in the capital cities – places where housing has become the least affordable – and you end up with a housing crisis and productivity slump today.

This isn't something that can be fixed with demand-side measures. It's also not something the federal government can fix on its own: if a future government is serious about addressing housing, it's going to have to get its hands dirty and start meaningfully dealing with the states.

Stating the problem

The reason there isn't much a federal government can do about housing is because constitutionally, it has no control hyper-local land use regulations (e.g. zoning). It also has limited control over the numerous state and territory regulations and codes for energy efficiency, safety standards, parking requirements, setbacks, height limits, and permitting processes, all of which can make housing less affordable.

These regulations affect the entire process from concept planning, to building, to final habitation. A recent AFR editorial estimated that state and local government taxes and charges alone add 20-40% to the cost of a new house. Add in all the other restrictions and "permission slip" requirements, which cost both money and perhaps even more importantly, time, and the burden can rise to 70% of the cost of a home.

That means to fix the housing crisis, a federal government has to work with the states. Labor's Housing Accord – at least when it was initially announced – appeared prepared to do that, with states committing to "expedite zoning, planning and land release for social and affordable housing", and to "working with local governments to deliver planning reforms and free up landholdings".

But that was 2022. I went through what the states planned to do to meet those stated goals, and it wasn't promising: most states just included catchy phrases to tick the box, like "streamlining the planning approvals assessment process" (VIC), or undertake "planning reforms that streamline planning approvals" (QLD).

When something concrete was offered, such as in NSW where the government pledged to reduce minimum lot sizes and roll out a "a consolidated package of planning reforms" (and actually did it), the actions have been significantly watered down following the dreaded "consultation" process and local push-back.

Most troubling – and this goes to the root of the problem with the Housing Accord and why it won't do much to improve affordability – is that every measure has some kind of "social and affordable dwelling" condition attached.

For example, the only projects that will be streamlined in NSW and receive "access to a 30% floor space ratio boost, and a height bonus of 30% above local environment plans", are those "that allocate a minimum of 15% of the total Gross Floor Area to affordable housing".

Victoria is the same, with its yet-to-be-revealed plans to "unlock and rezone surplus government land" coming with the caveat that any projects "include a minimum 10 per cent affordable housing target on these sites".

Despite the name, these conditions make housing less affordable, because they lower the profitability of market-rate housing. At the margin, some developments will then become unprofitable and limit supply, raising market housing prices.

If you have a shortage of housing, it doesn't matter what type of housing you build as long as you build something. Even if it's new luxury housing, that supply will ever so slightly depress the price of the existing homes that are vacated by wealthy people moving their new luxurious digs, making them more affordable to the next income tier, some of whom vacate their slightly less-nice homes, and so on.

There's also the usual allocation problem with "affordable", i.e. government-subsidised, housing: when you give something away for less than the market rate, people will queue for it. So, well-located units are not necessarily allocated to young people who want to move to where the good jobs are, but to people who have been on the waiting list for the longest, regardless of their relative preferences or needs.

Public housing isn't necessarily the answer, either. What matters for incentives are effective taxes, and that includes benefits that 'step off' at certain levels of income. A recently published study from the US found children from public housing projects that were demolished "earn 15 percent more at age 26 relative to children in comparison projects".

The reason? Demolishing the public housing forced affected families to move, improving job accessibility, with the largest gains amongst those in big cities and "distressed" neighbourhoods. Houses don't move, and the last thing you want to do is trap people in an economically-struggling region because the effective marginal tax they would face by moving – say, for a better job – makes it uneconomic.

Like "affordable" housing, public housing can keep a few initially lucky low-income people stuck where they are, only if they remain low-income. If you want to hurt poor people, tying them to a specific income level and home is a great way to do it. It's all just inefficient and productivity-sapping, and has rightly been dubbed the "most expensive possible way to help the smallest number of people".

What the federal government can do

"Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it, misdiagnosing it, and then misapplying the wrong remedies." — Quote attributed to Groucho Marx

The reason the federal government hasn't properly addressed the housing crisis is because it's a supply-side problem over which it has very limited influence. So, we get things like the Housing Accord with its affordable housing mandates and a bunch of demand-side measures from both Labor and the Coalition, all of which will at best not make the situation any worse.

But that doesn't mean there's nothing a future federal government that doesn't mind getting its hands dirty could do. I've written before about the need for housing coercion, and barring a referendum changing the relative powers of various governments, that's realistically one of the only things a federal government can do.

The fact of the matter is that if we want to ensure that we have enough houses to satisfy demand at prices people can afford, we have to reduce the regulatory barriers that make construction an unnecessarily expensive and drawn-out process. And that means getting the incentives – which are currently too heavily balanced in favour of local obstructionism – right.

The good news is that the federal government has levers it can pull. It distributes a lot of money to the states: in 2022-23, NSW received $18.5 billion in non-GST grants. That's plenty of money it could hold ransom unless the state built enough homes.

This isn't some new idea. Canada's likely next Prime Minister, Pierre Poilievre, has a bill that "will make it a legal requirement that municipalities approve and allow construction of affordable housing around every single federally funded transit station", and "will incentivise cities to speed up and lower the cost of building permits and free up land by linking the federal dollars they get to the number of homes that actually get completed".

The target is a 15% annual increase in construction, "which would double home construction within five years at a compounding rate", and it's up to provincial and local governments to decide how they choose to achieve that:

"Those that beat the target by 1% will get 1% more money; those that miss it by 1% will get 1% less. It is a simple mathematical formula for which no new forms, no new bureaucracy and no new delays are required."

A future Australian government could do something similar with its grant distributions.

There are other less-impactful but still useful things it could do, too. For example, the Commonwealth owns a lot of valuable land in the capital cities that it currently uses for "efficient government use" (mostly the military), but which if subject to a cost-benefit analysis may well be a lot more efficiently used for home construction. It could auction that off and use the proceeds to further incentivise the states to act.

It could also produce a credible plan to reduce deficit spending, lowering long-term government debt and mortgage rates along with it, which would be a demand-side measure at no taxpayer cost and without unintended consequences.

It could also educate people on the importance of supply. A new paper found that while most people "do not believe that more supply would lower prices" – and instead blame "high prices on landlords and developers" – that view can be changed:

"Learning about housing markets increased support for development among homeowners as much as renters, contrary to the 'homevoter hypothesis'. The treatments did not significantly affect the probability of writing to lawmakers, but an off-plan analysis suggests that the advocacy video increased the number of messages asking for more market-rate housing."

Thankfully, most Australians already appear to understand the need for supply:

When demand pushes prices up above the cost of house production, more construction will drive prices back down – but only if it's allowed to. Australia needs to let its housing markets be markets again: there are just too many ways for a handful of individuals to block new housing that would benefit many thousands.

Unfortunately, neither the current federal Labor government nor the current Coalition opposition have policies that will meaningfully address the actual causes of the housing crisis, so barring a significant slowdown in population growth, I just can't see it getting much better any time soon.

Member discussion