The Kiwi in the coal mine

New Zealand's economy is in trouble, with a double-dip recession and shrinking per capita growth. The decline stems from a lack of productivity reforms and an excessive focus on equity over efficiency. But Australia isn't much better, and we could easily join them if policymakers get complacent.

It's ANZAC day tomorrow, so in honour of our Kiwi friends I thought I'd take a quick look across the ditch and see how New Zealand's economy is faring. And let me tell you, if you thought the Australian economy was in for a rough patch, it could be a lot worse!

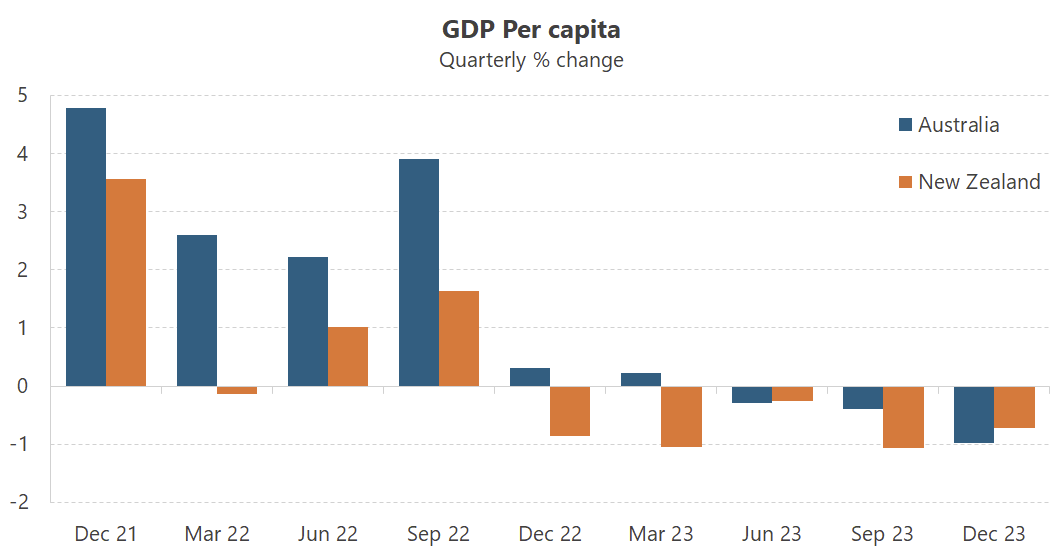

For decades, the once-vaunted New Zealand economy has been falling behind other advanced economies on several key indicators. It's currently in its second technical recession in the past 18 months (defined as two consecutive quarterly contractions), and perhaps even more worryingly on a per capita basis has been shrinking for five consecutive quarters. By contrast, Australia has 'only' contracted for three consecutive quarters (woohoo!). Seriously though, we have nothing to boast about; for the past two years we've barely had any per capita growth and in the most recent quarter we actually underperformed the Kiwis.

How did it all go so wrong?

Once at the frontier of global productivity following an ambitious reform agenda in the 1980s, the Kiwis now languish towards the back of the advanced economy pack, which has contributed "to a rapid increase in unit labour costs, undermining New Zealand's competitiveness".

That's perhaps best epitomised by the fact that the Kiwis recently scrapped their Productivity Commission, which had disintegrated from the inside with the appointment of commissioners who were "not at all actually focused on or expert in productivity". New Prime Minister Christopher Luxon laid out the dire situation with a comparison to Eastern Bloc countries and, of course, Australia:

"New Zealand's economy is now less productive than vast swathes of the former Eastern Bloc, including Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia and Lithuania … The median full-time worker in Australia now earns $20,000 more a year than someone in New Zealand."

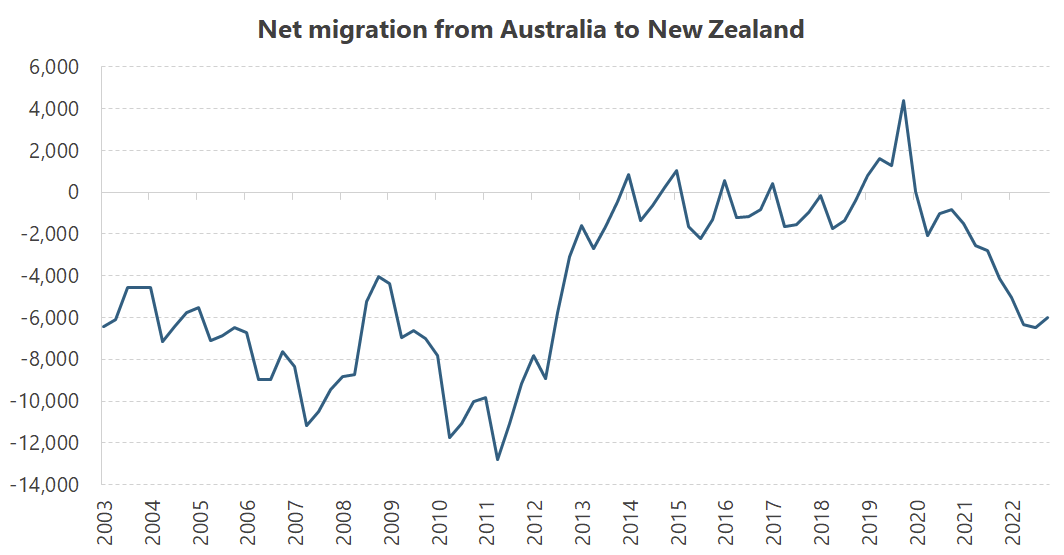

That wage differential and the fact that Kiwis can work freely in Australia has led to an "emigration of skilled New Zealanders". The brain drain slowed when the mining investment boom dried up and actually reversed during the pandemic, but since then it has once again deteriorated.

What led to the New Zealand productivity decline? Most advanced economies have experienced a productivity slowdown, but the Kiwis have done especially poorly. According to former RBNZ, Treasury and IMF economist Michael Reddell, that's partly because neither major political party has had much interest in productivity other than when it makes for a good headline:

"I was an enthusiast early on for the idea of the creation of a Productivity Commission in New Zealand. It was one of the recommendations of the 2025 Taskforce report in 2009 and was also a bit [of a] cheap gift to the ACT party, then supporting National in government. Supporters tended to look across the Tasman at the contribution the Australian Productivity Commission had made to enriching policy research and analysis there.

...

But I was also fairly sceptical from early on as to just how long the new New Zealand Productivity Commission would last. That wasn't because I expected them to do bad work or even fail to contribute to the New Zealand debate (and our aggregate productivity performance was dire and longstanding). It was more the track record: the Monetary and Economic Council had come and gone, as had the Planning Council. Both had at times produced useful papers, but that hadn't saved them. It wasn't clear what was likely to be different about the Productivity Commission over the medium term, whether what saw them off was getting offside with the government of the day, fiscal stringency, lack of critical mass or whatever. There wasn't, after all, any sign of a passionate embrace by either main political party of the cause of markedly lifting New Zealand's productivity growth."

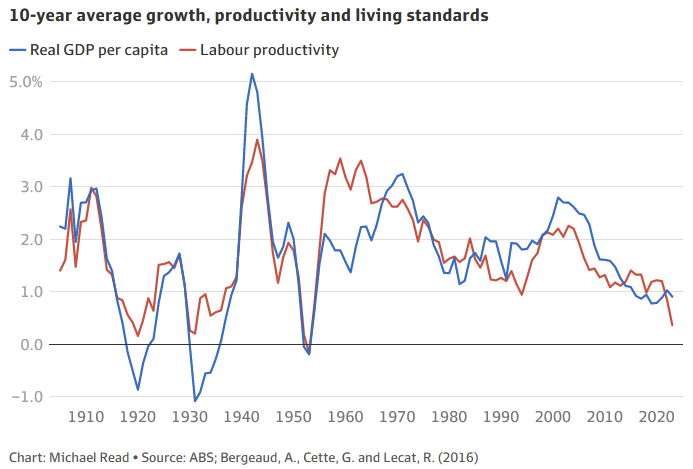

Between 1996 and 2023, labour productivity in New Zealand grew at just 1.2% a year versus 1.8% in Australia. Good for us, right? Sure, but you must remember that while we both passed important productivity-boosting reforms in the 1980s and then did very little on that front for decades (and counting), we also happened to have a mining boom during those years; the Kiwis were not so fortunate.

That's a key the reason for the difference between the two countries: Australia experienced much greater levels of capital investment than did New Zealand. An interesting new report from NAB found that "in the decade before the pandemic, about 70 per cent of the [Australian productivity] gains came from the fruits of the mining investment boom, which was unlikely to be repeated".

Productivity growth in both Australia and New Zealand is now in the gutter (negative in both countries in 2023), and our policymakers won't have another mining boom to rescue us this time. If we don't get meaningful productivity-boosting reform soon, then we're destined to end up like the Kiwis:

"Australians will experience an even slower improvement in real wages in the years ahead than was forecast in last year's Intergenerational Report".

I think it's worth reminding ourselves that growth and prosperity are not guaranteed; in fact, the default human state is the opposite of that: poverty. Economic policy is all about trade-offs, and it may be that we, as a society, choose more equity in exchange for less efficiency. But if we get the balance wrong and undermine important institutions in the process, in the long run we may end up with less equity and efficiency.

Which brings me to Jacinda Ardern.

Ardern's lasting legacy (feat. Chris Hipkins)

When Labour's Jacinda Ardern was elected in 2017 on the back of an unexpected, unholy alliance with the nationalist/populist New Zealand First Party, she promised that her government would be "active... focused, empathetic and strong".