The need for tax reform

Last week, Treasurer Chalmers penned a letter to the AFR arguing that in modifying the stage 3 tax cuts, his government "chose relief and reform". Relief, sure (except for those earning over $146k!) but I was curious as to what reform was being proposed. In his essay, the Treasurer mentioned it 12 times – including in the title itself – but as far as I could tell all he's doing is modifying the thresholds of a single tax.

Reading the letter itself did not provide any clarity. Here's the key passage describing the reform part of the stage 3 tax changes:

"By dropping two rates and lifting two thresholds, we are reforming the tax system, returning bracket creep where it has the most impact, and providing cost-of-living relief and reward for effort right up and down the income scale, with a bigger emphasis on middle Australia.

That's superior relief and superior reform."

Is returning some of the recent bracket creep to different people than was already legislated – while taking a cheeky extra $28 billion in taxes over the next decade – now called "reforming the tax system"? I don't think so; reforming the tax system would involve doing something like eliminating bracket creep. To make sure I wasn't completely missing the mark, I plugged the essay into the newly-updated Google Bard and asked it what was being reformed. It was also perplexed:

"The plan primarily focuses on adjusting tax brackets and rates, which falls under relief rather than transformative reform. True reform often involves tackling deeper issues like:

Closing tax loopholes: Does the plan address loopholes benefiting specific industries or individuals?

Simplifying the tax code: Does it streamline the system, making it easier for taxpayers to navigate?

Broadening the tax base: Does it explore alternative or additional sources of revenue beyond income taxes?

Without addressing these aspects, the 'reform' label seems less convincing."

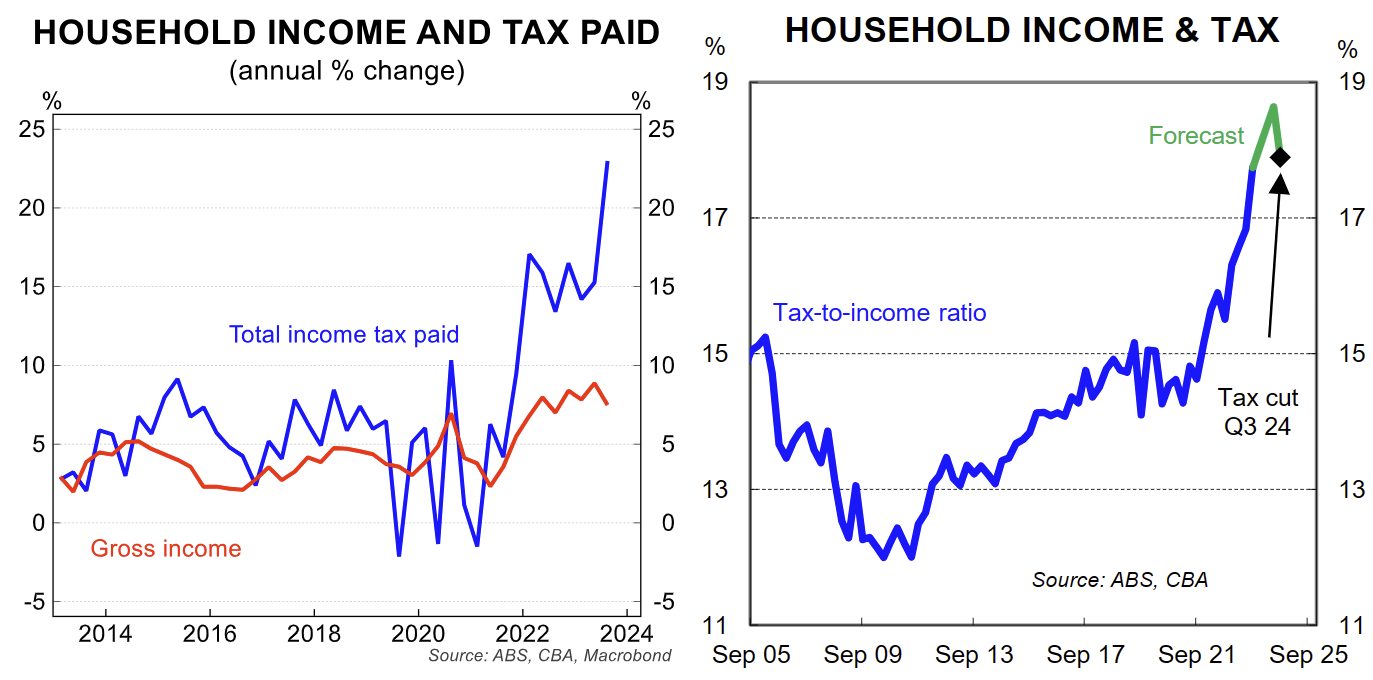

Right. According to a human, CBA's Gareth Aird, the tax cut itself is little changed, and tax paid as a share of household income will continue to rise. Aird also created the following charts to show just how bad bracket creep has been and will continue to be after the 'reformed' stage 3 cuts.

Indexation isn't some strange concept

In the US, the federal government (Economic Recovery Tax Act 1981) and most states indexed their tax brackets to consumer prices following the high inflation of the 1970s. Around 45% of OECD countries now index their income taxes to consumer prices or wages. It's not a perfect solution: because the adjustments are usually done annually, periods of high inflation can create fiscal drag, where taxpayers are "dragged" into higher tax brackets. Short-term bracket creep, if you like. When inflation starts to slow, the reverse happens and government revenue falls.

In countries that don't do any indexing of income taxes, people instead rely on the benevolence of the government to return bracket creep. In Australia, most years we either do nothing or tinker at the margin until the time comes for a big "tax cut" announcement, which only temporarily restores the balance.

The new stage 3 tax cuts will bring the median voter's income tax burden back to around 2015 levels, still a full percentage point above the 2013-lows. After July, it's all downhill: even assuming a modest 3.5% annual increase in nominal wages, bracket creep will see the median full-time income earner's tax to income ratio surpass the most recent high (2020) in just five years, assuming no further "reform".

The costs of bracket creep

There are real costs to relying on this lazy system of revenue raising, and not just the wasted energy our political class spends debating how much to 'give back' every few years. Economists in the US have estimated that raising taxes through bracket creep is less efficient than simply changing marginal tax rates, because of the distortions it causes to "private work effort and saving decisions":

"The net result is that the utility of the average individual is higher in the long run if inflation indexation is maintained and if tax revenues are raised by permanently adjusting structural tax rates."

More recent work found that in a system that enables bracket creep, the longer governments leave it between adjustments (tax cuts), the bigger the reduction in "employment, savings, and output".

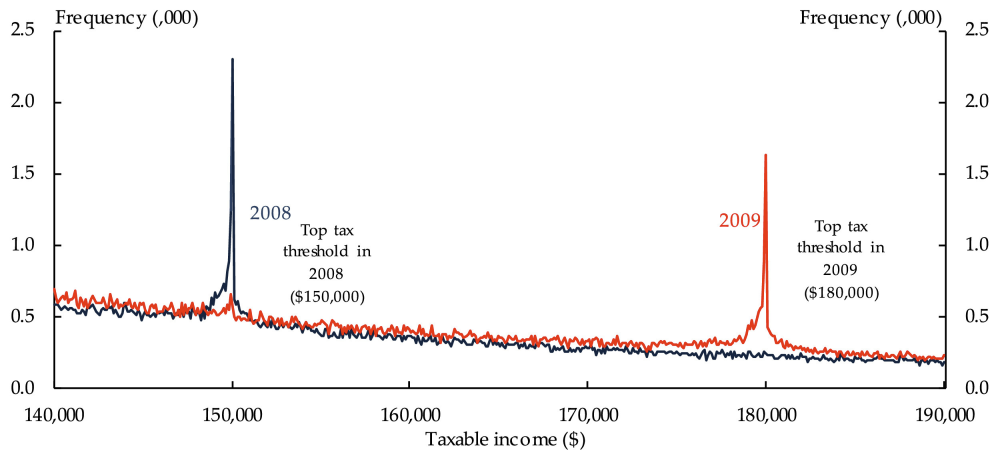

People don't like paying higher tax rates and will take steps to minimise their taxable income above thresholds. In a progressive taxation system like Australia's, that demonstrates as 'bunching' around tax brackets.

People exert less effort, pass on promotions, take unpaid days of leave, hire accountants to minimise tax (trusts, incorporating, etc), or even engage in the informal cash economy because the marginal dollar they might earn would be taxed at a higher rate.

When governments change those marginal tax rates, the bunching also moves. A paper published in Labour Economics last year showed how the change in Australia's top marginal tax bracket from $150,000 in 2008 to $180,000 in 2009 shifted almost all of the bunching forward to the new level.

With bracket creep, as people get paid more – purely from inflation, i.e., even assuming no productivity changes – the amount of people bunching around and moving into new thresholds gradually increases, causing welfare and efficiency losses as people adapt. Not everyone wants to pay 45c on the dollar, or 37c, or 30c, or even 19c, especially if it could mean losing certain income-linked benefits. Bracket creep also reduces the progressiveness of the tax system itself, as more and more people are gradually squeezed out of the lower thresholds.

Sometimes a thought experiment can be helpful. Imagine if the top tax bracket were 100% on incomes above $190,000, instead of 45%. If that were the case, how many people would work beyond that point? Close to zero – you'd get a huge bunch right below $190,000. Some people on lower incomes already face marginal tax rates well above 100%, because of the various benefits they stand to lose once they earn an additional dollar over some fixed level. What incentive is there to work when you lose money by doing it?

Australia's top marginal tax rate is significantly lower than 100%, but as the charts above showed, that's still enough of a disincentive for thousands of people to reduce their work effort and keep their taxable incomes below the threshold.

Fixing this inefficient system isn't difficult, as half of OECD nations have already demonstrated. But it comes down to political incentives: why would a politician want to kill a cash cow that also allows them to buy votes with "relief" every term they're in government?

Meanwhile, when inflation is going to cost the federal government revenue, politicians very quickly act to solve the problem. For example in 1983, after a decade of inflation averaging in the double-digits, the excise on alcohol was linked to changes in consumer prices every six months. Yesterday that process happened for the first time this calendar year, raising taxes on tobacco, alcohol and fuel for everyone. Australia "now has the third highest spirits tax in the world, behind Iceland and Norway" – all without the government having to lift a finger.

While those automatic tax hikes hurt people (especially those most disadvantaged), fixing income tax to automatically help people would only take a Treasurer who actually wanted to reform the system, rather than pay lip-service to it; to put his or her foot down and get it done! No doubt Treasury has already done lots of work on it; bracket creep isn't some new thing that requires innovative solutions.

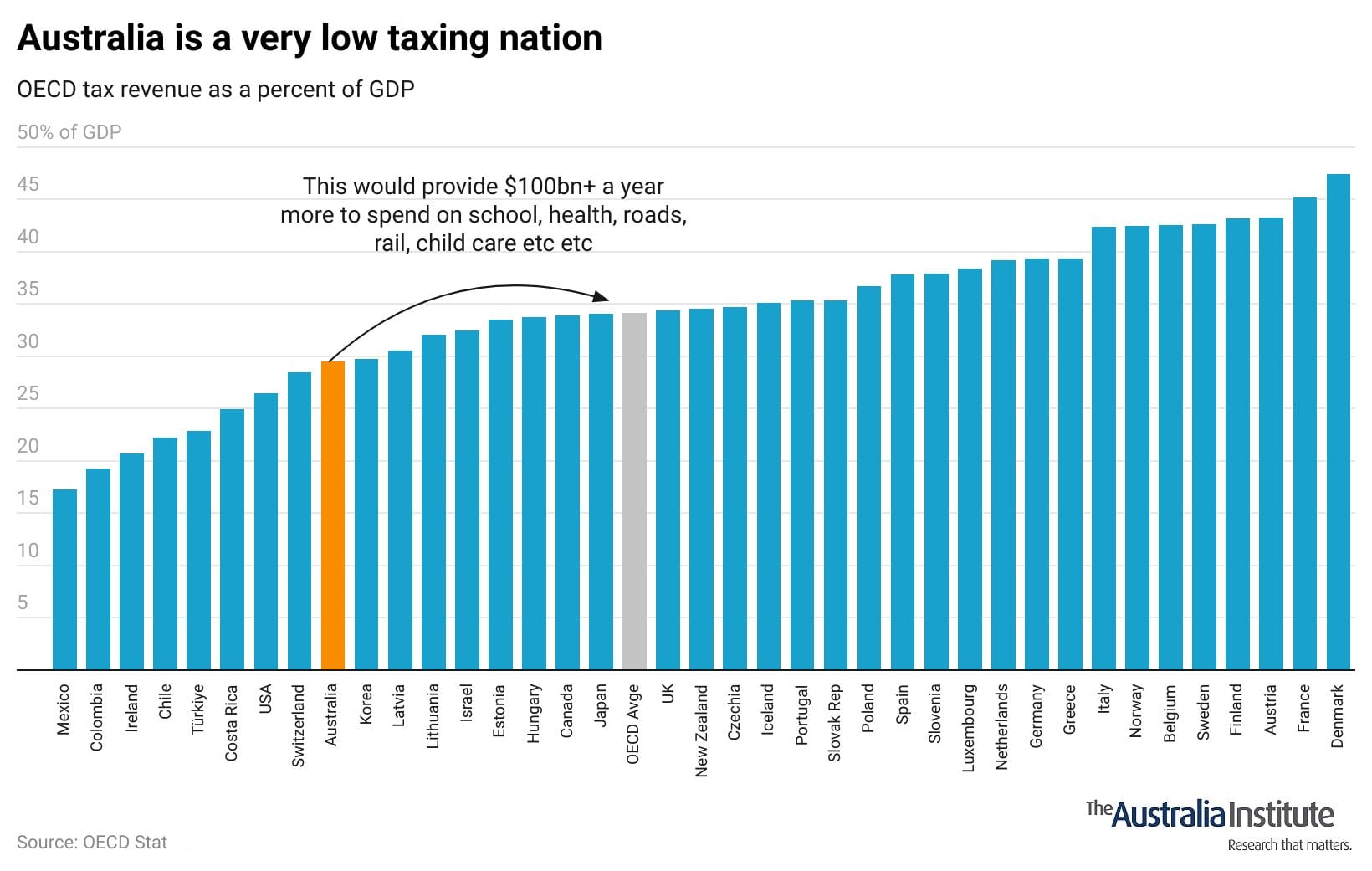

We're already a high taxing country

The thing is, the Australian government doesn't need to rely on bracket creep to raise revenue. If it wants to spend more, it has the power to raise taxes. We're also a country that already taxes people a lot, so it's not even clear that our marginal tax brackets would need to rise in the absence of bracket creep. Just set them once and move on.

But wait, you say! Australia is a low taxing nation, isn't it? At least that's what you might think by looking at the cross-country data: Australia collects less tax revenue than most other OECD countries, as shown in the following chart from the Australia Institute.

But our government doesn't collect social security contributions in Australia. Unlike most other countries, we pay 11% of our incomes into mandatory superannuation instead, and those payments aren't included as tax revenue by the OECD. If we take out social security contributions from the other countries to even the playing field a bit (Denmark finances pensions out of general revenue, so it's not perfect), the chart instead looks like this.

Using the momentum for reform

I agree with the Teals and independents such as David Pocock that a review of our tax system is long overdue. It's rare to have the public interested in tax reform, so using the momentum caused by the recent inflationary period to get a review would be a good outcome, if for no other reason than to force politicians to plainly state why they're not going to implement it all.

Alas, I don't think a review will find what they're looking for, unless the terms of reference is sufficiently cooked. According to the article linked by Pocock, the tax benefit of negative gearing was just $2.7 billion in 2021, or around 0.4% of total government revenue – hardly worth getting too worked up about, especially given that the Grattan Institute has previously estimated that abolishing it and halving the capital gains tax concession would reduce property prices by just 2%.

Pocock might find more support for changes to the poorly designed and ineffective PRRT (petroleum resource rent tax), but the large fossil fuel subsidies he hates are mostly due to estimates of untaxed externalities – pollution, environmental damage, climate change – and even household electricity bill relief (for which Pocock voted). Just how likely is this Labor government to propose a new carbon tax – despite the clear efficiency gains against the alternative of governments attempting to 'pick winners' – given how politically damaging the last one was for Gillard government?

Then there's effectively taxing "multinationals" (I assume he means those that engage in transfer pricing shenanigans), which is easier said than done without creating unintended consequences greater than the revenue raised.

Nevertheless, a new review would still be helpful. The last tax review in this country was released in 2010 under the stewardship of former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry. It produced 138 recommendations, almost all of which remain unimplemented. While Treasurer Chalmers has indicated he's not done with tax, having already instructed Treasury to look at family trusts, his idea of tax reform appears to be looking for ways to collect more of it, rather than making it fairer, more equitable, or efficient. Chalmers has also said he prefers "incremental" changes, rather than "big bang" reform. According to Henry, that's like shifting the deckchairs on the Titanic:

"No amount of incrementalism is going to meet our fiscal challenges, far less turn around two decades of declining average living standards."

Regular readers know that I'm a fan of "big bang" reform. But if that's beyond this government – which it looks to be – then some incrementalism would be fine, and fixing bracket creep for good would be an excellent feather for Chalmers to put in his rather empty reformist cap.

Member discussion