The RBA's inflation trap

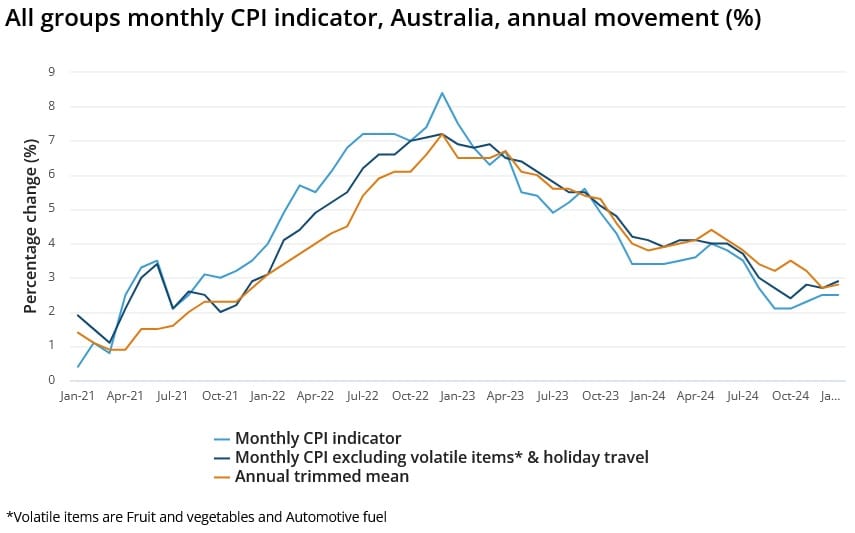

The first wave of data since the Reserve Bank of Australia's (RBA) "hawkish cut" last week has dropped, the most recent of which was this morning's monthly consumer price index (CPI), which came in at a flat 2.5%, although the trimmed mean ticked higher to 2.8%:

The usual cautions about the reliability of the monthly inflation data still apply, but this was a decent result for the RBA, especially as key outlets for past inflation—construction costs, insurance fees, and rents—all eased in the month, the latter "reflecting recent increases in vacancy rates across most capital cities" (hurray!).

However, the uptick in the trimmed mean measure—which excludes electricity and all of the subsidies that help to pull headline inflation down—will be slightly concerning, given it was the first acceleration since October 2024 (and rates had not yet been cut in January).

Moreover, the seasonally adjusted headline figure increased from 2.5% to 2.7% in January, or 0.6% in the month—which corresponds to an annualised rate of 6.9%.

Early days, to be sure, but all of this suggests that the RBA isn't out of the woods yet, especially as history shows that inflation has a nasty habit of coming back right when you think you've got it under control.

Once bitten, twice shy

During a recent testimony to Parliament, governor Bullock confessed that the RBA is still smarting from its recent mistakes:

"What's also playing on the board's mind is that the board also doesn't want to be late [in cutting rates].

Arguably we were late raising interest rates on the way up. We didn't respond as quickly as we should have to rising inflation.

"I think the board has been quite cognisant of the fact… that if we're going to start reducing interest rates, then we need to be thinking of doing it not when we are already back in the [2-3 per cent target] band, but as we start to get more confidence we're coming back to the band."

It's a fair point, and is a relatively hawkish signal during an easing cycle: the RBA has ripped the Band-Aid off, so now it can sit back and 'observe the data' before making another move, without being criticised for being late again.

But it's also a risky strategy. As I referenced last week, inflation is like cockroaches; if you fail to fully exterminate the infestation then expectations will change, people start raising prices (and asking wages) today in anticipation of future inflation, and it becomes something of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I think this is where the RBA's dual mandate gets it into trouble. There are lots of factors that contribute to unemployment, both nominal and real, whereas inflation (properly defined as a sustained increase in the aggregate price level) is purely a nominal phenomenon. In the long run, the RBA can only influence nominal variables, so if rising unemployment were caused by real factors – say, labour reforms that make the market more rigid or drive up wages above productivity – then any monetary effort to 'fix' it risks stagflation.

This echoes concerns from some US economists, who note that inflation has risen to 3% from 2.4% in September at the same time as hiring has slowed and quit rates have fallen, suggesting some labour market weakness:

"[T]he Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 25 basis points in December, a decision that now appears mistaken. That is more likely to incite than defuse inflationary pressures... If you accept the notion that inflation is more likely to rise than fall, and that the labour market is more likely to worsen than improve, then the chances for a modest stagflation are reasonably high."

That outcome is by no means a certainty, although inflation expectations have been ratcheting up in recent months and are "now well above the 2.3–3.0% range seen in the two years prior to the pandemic".

Real wages are still growing, indicating demand pressures

Other data released over the past week include the monthly job figures for January 2025, the wage price index (WPI) for the December 2024 quarter, and average weekly earnings for November 2024.

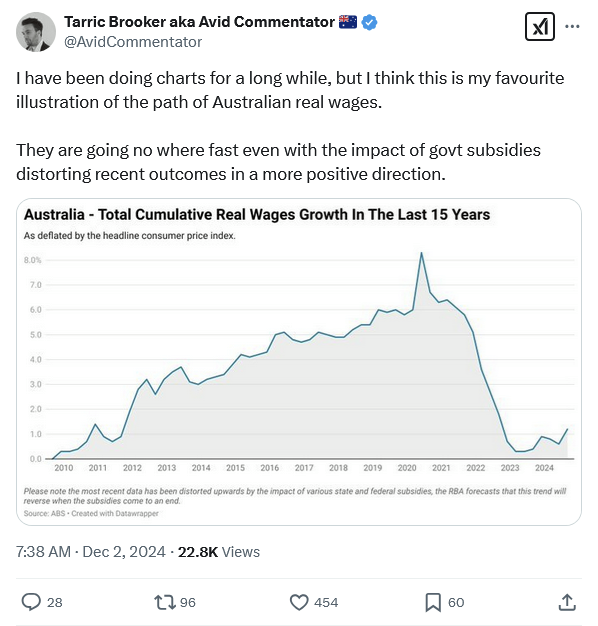

So, what's happening to wages? You'll often see charts that look something like this trotted out by the media:

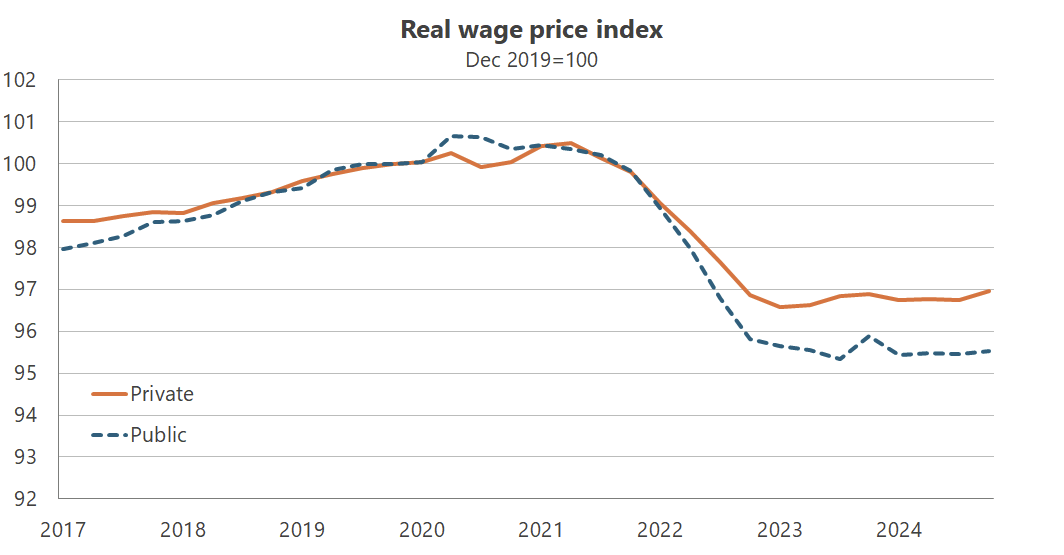

There's nothing technically wrong with the data being presented. Real wages, as measured by the WPI, have indeed fallen for both the private and public sectors:

But the WPI isn't telling the whole story; it only measures the job, not the worker. And the main way people secure themselves pay increases is through switching jobs.

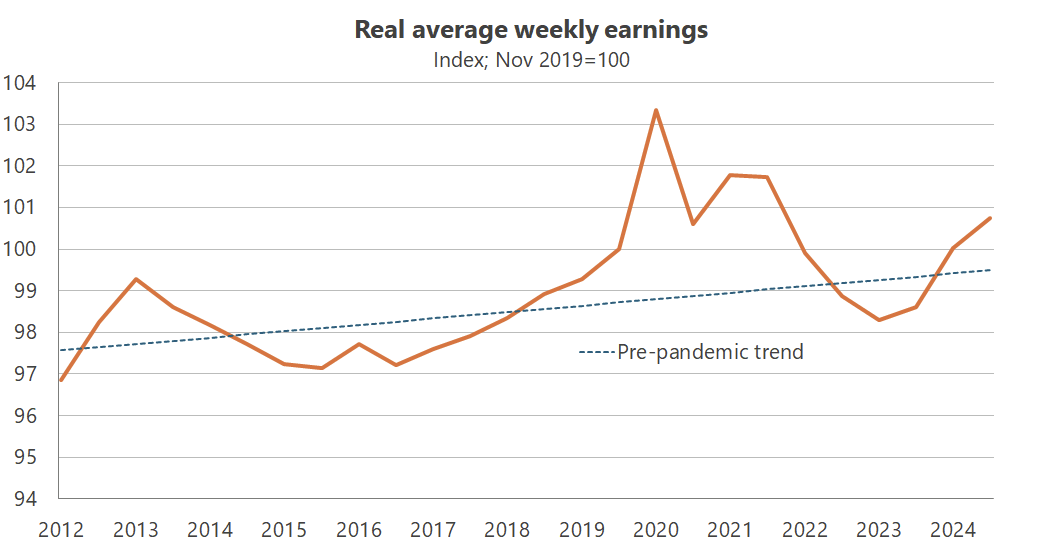

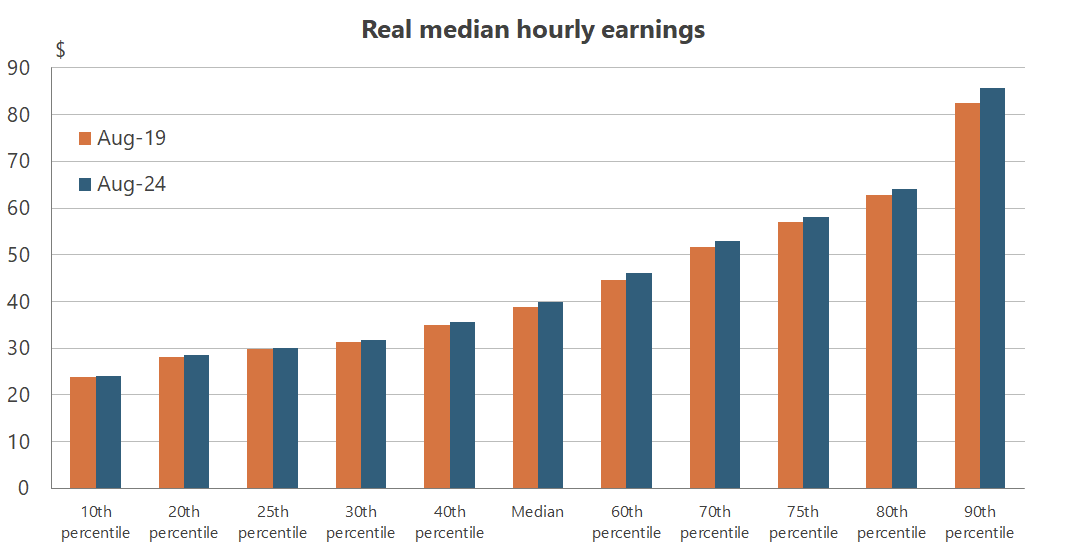

Basically, if more people than usual are moving into higher paying occupations or roles, or working more hours, it can boost average and median wages without affecting the WPI, which looks to be what we're seeing in the data:

All income groups have seen their real incomes increase since 2019, both on an hourly and weekly basis. Unfortunately the median earnings data are even less frequently updated than average earnings, so the most recent data point is August 2024. But there's no reason to think, with real average earnings and the WPI rising in the time since, that it hasn't subsequently grown by even more:

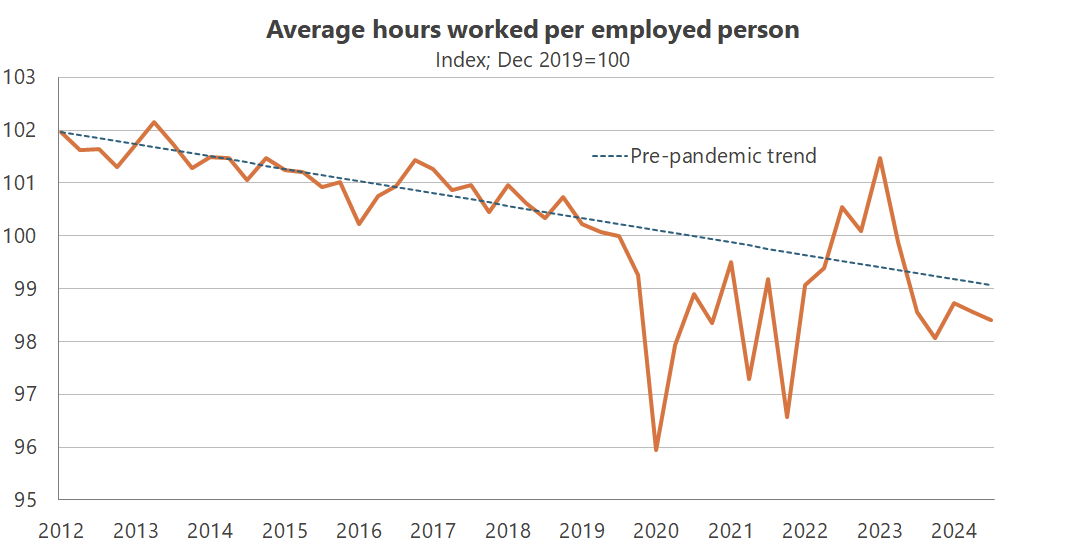

While the total number of hours worked has increased due to the record-high employment to population ratio, on average each worker is spending fewer hours at their job than they did prior to the pandemic.

That leaves one likely explanation: a compositional shift in employment toward higher-paying jobs, with more workers finding employment in roles with higher wages, even if wages for specific jobs have not kept up with inflation.

But don't just take my word for it; the Productivity Commission drew a similar conclusion in a September 2023 report:

"The definitional and methodological differences between these data sources can lead to significant variations in wage growth rates. While variations tend to be short-lived for most measures, the divergence between the WPI and other wage measures has risen over time, testimony to its failure to account for shifts in the type of work to higher paid jobs. Higher productivity and associated wages in an economy are often associated with shifts of employees between low and high-paying jobs, which the WPI fails to measure. Accordingly, while useful for some purposes, the WPI is not a valid measure of the total returns to work."

Here's why that matters for the RBA

So, the labour market is hot, and wage pressures are in fact rising. What might that mean for inflation?

Wages rising faster than productivity don't necessarily lead to inflation, unless they're being paid for with new debt that is not expected to be repaid with higher future taxes or lower spending. If that's the case, it changes behaviour today, as people start selling/spending more government debt than they would otherwise, which starts to put pressure on prices:

"First, we try to buy assets. The asset prices go up. Then, feeling wealthier, we try to buy goods and services. The goods and services prices go up until the real value of the debt — the amount of debt divided by the price level is its real value — is back to equal what people think the government will be able to pay off. That's the fiscal theory of the price level in a nutshell.

It's still too much money chasing too few goods. But money includes all nominal government debt, not just money itself."

Last week, the RBA released an updated chart pack and Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP), which offered some great detail into what has been going on in the labour market under the Morrison/Albanese governments.

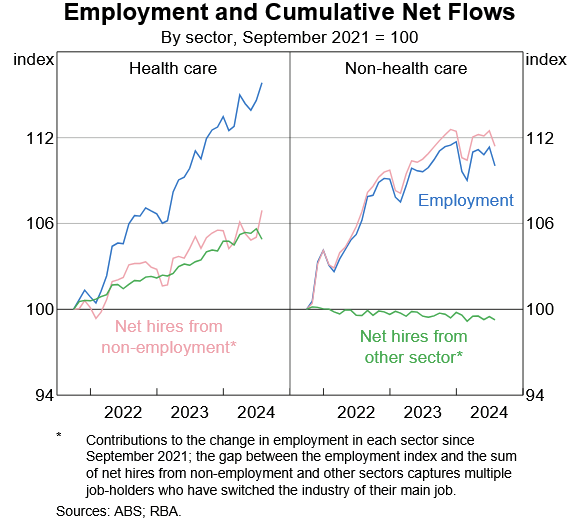

Take, for instance, these charts:

According to the RBA:

"Strong demand for labour in the health care industry has drawn in workers from other industries, as well as some who were not previously employed. Growth in health care jobs has partly reflected inflows of workers from other industries. These workers have tended to come from the administrative services and household services industries, including hospitality, arts and recreation, and education."

The sectors from which the health care industry has been drawing labour are relatively low-paid. And while the RBA notes health care wages haven't outpaced the WPI, that obscures a key driver: workers switching from low-paid sectors like hospitality to better-paying, government-funded health roles that the WPI can't detect, adding to demand pressures.

Based on its commentary, it's not clear that the RBA fully understands that nuance. And that's a huge risk, because the best way to solve inflation is with fiscal, monetary, and microeconomic policies all working in tandem. If a tight labour market and rising wages are being financed with new debt without a credible plan to pay for it all, inflation may not subside as easily as the RBA expects.

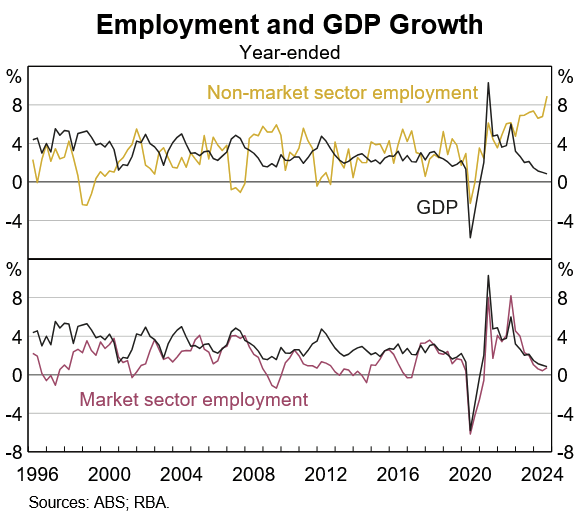

And the Australian labour market is tight, driven almost entirely by the non-market sector, namely government-funded health care:

Combine that with monetary easing, virtually zero microeconomic reform, and a fiscal policy that looks to be moving further in the wrong direction, and those inflationary cockroaches may well scuttle back later this year:

"Labor has made at least $123.6 billion worth of discretionary spending decisions from its three budgets on areas such as childcare subsidies, aged care, health, housing and green energy, according to an analysis by The Australian Financial Review.

...

Since the beginning of this year, the government has also made major election promises worth more than $20 billion, including $8.5 billion for Medicare bulk billing, $7.2 billion for a Queensland highway, $3 billion for the NBN and $1.7 billion to rescue the Whyalla steelworks in South Australia. At least $3 billion of the promises will be accounted for in future budgets and many other measures taken during the first term are not technically counted in the $123.6 billion.

The Coalition's willingness to match most of Labor's big ticket election promises this year, with Opposition Leader Peter Dutton only making vague offers on Monday to find $6 billion in annual savings from sacking up to 36,000 public servants, has further alarmed budget watchers."

By one estimate the Albanese government has spent, or has committed to spend, an additional $204 billion between when it was elected in 2022 and 2025-26 – equivalent to 2% of GDP per year, half of which was due to new government spending decisions. Many state governments have been even worse.

That's precisely the opposite of what a government should do during an inflationary shock, and it has made the RBA's job all the more difficult.

Finally, I'm also worried about the increasing politicisation of the RBA. Everyone from the Treasurer and state Premiers to the leader of the opposition were leaning on the RBA to cut rates ahead of its meeting last week, which may have influenced its decision to cut (the Treasury Secretary, a political operative, also sits on the board).

There's a strong historical correlation between central bank independence and low, stable inflation, so if the RBA has been even a little compromised, that will also raise the likelihood that inflation will return.

To summarise, there's a serious risk that the RBA made a mistake by cutting rates last week, given strong debt-financed wage pressures, fiscal exuberance, low productivity, and rising global economic uncertainty.

And that will be costly. To quote governor Bullock:

"The impact of high inflation over the past couple of years has permanently increased the price level. That has hurt everyone but particularly those on lower incomes and the more vulnerable."

I just wish she was less worried about the optics of moving too slowly, and more concerned about the very real harm that failing to crush inflation will do to people and the country, especially the least well-off among us.

Have a great day.

Member discussion