The return of the Tariff Man

The United States has, in recent years, drifted towards protectionism. It all started with Donald Trump, who quite literally called himself the "Tariff Man". But following the election of Joe Biden, not all that much has changed. Trumps tariff's all remain in place, and following a recent review, Biden has now passed a bunch of his own:

"The White House said the tariff increases were designed 'to protect American workers and American companies from China's unfair trade practices,' including forced technology transfers and theft of intellectual property. It also cited China's 'growing overcapacity and export surges that threaten to significantly harm American workers, businesses, and communities.' The products subject to the increased tariffs were 'carefully targeted at strategic sectors—the same sectors where the United States is making historic investments under President Biden'."

I can't help but think that Biden is doing this for two main reasons. For one, Biden is deeply unserious on all matters economics. A few weeks ago the head of his influential Council of Economic Advisers, Jared Bernstein, couldn't answer a basic question about how money works. Now that's completely understandable, given Bernstein's background is in music and social welfare. But that Biden would appoint him to one of the most influential economic roles in government – to the head of an executive body "charged with offering the President objective economic advice on the formulation of both domestic and international policy" – suggests he just doesn't care all that much. For Joe, it's all politics.

Which brings me to the second reason: with an election in November, Biden wants to one-up the Tariff Man himself by becoming him. Unlike Trump, Biden has no ideological obsession with trade balances; he doesn't care enough to even form the fallacious view that foreign trade is the economic equivalent of "raid[ing] the great wealth of our Nation".

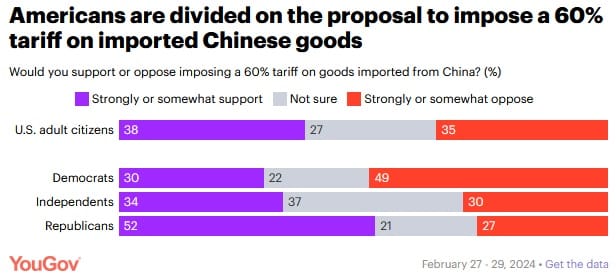

But Biden is a skilled politician who knows that tariffs are popular with the powerful interest groups it benefits, such as Detroit automakers and their workers, that could swing to Trump. He also knows that they're not unpopular enough with voters to cost him all that much. The fact he's specifically targeting China also helps, as it proves he's not "soft", given the evolving situation in Taiwan and the fact that China is deeply unpopular with the American public. In fact, more independents and Republican voters would support a massive 60% tariff on all Chinese goods than those who would oppose it.

A 60% "or higher" tariff is the figure Trump has proposed. Biden's are significantly smaller and more targeted than that, but the fact that most Americans in favour "say they would support increasing tariffs even if doing so leads to higher prices for American consumers", suggests that the trade wars will be around for at least another four years regardless of who wins in November.

In a historical context, tariff rates are still low

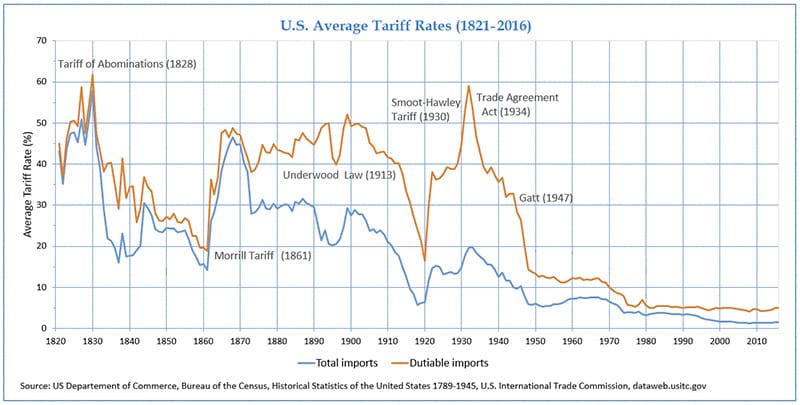

The good news is that, despite the new tariffs, overall rates are still quite low; we aren't even close to the bad old pre-WWII days.

Oxford Economics' Ryan Sweet said the US trade-weighted average tariff on goods was 1.6% prior to Trump, after which it rose to 3.1%. It then dropped to 2.7% prior to Biden's new tariffs (patterns of trade shift in response to tariffs), which will "permanently add 0.14 percent to the effective tariff rate".

Despite their small relative size, Trump's tariffs were still economically destructive and did very little to "counter" China. As Mary Lovely of the Peterson Institute for International Economics testified:

"Analysis of the four waves of trade-war tariffs finds that they fall heavily on producer inputs, that they tax imports that have no obvious relation to the cause for action, and that they omit exports that may have unfairly benefited from the practices identified by the investigation. This pattern of levies raises basic questions about the efficiency and fairness of their design."

After Trump imposed his tariffs, trade simply shifted. Other countries started importing more from China and exporting more to the US. Biden's tariffs will do the same: sure, the US might produce more domestically and import more from "friendly" countries, but those countries will, in turn, import more from China. There will be a loss of efficiency as trade becomes more roundabout, but not much will actually change.

National security can always justify protectionism

The malleability of global trade is why Biden has called in the economists. Janet Yellen, who had a long and distinguished career as an academic economist before accepting the job as Treasury Secretary, recently told a European audience that:

"China's industrial policy may seem remote as we sit here in this room, but if we do not respond strategically and in a united way, the viability of businesses in both our countries and around the world could be at risk."

The thing is, it's easy to lose a trade war. Yellen needs European countries to join if it's to have a chance at success, if success is defined as weakening China's manufacturing sector. Why? Because if the US goes at it alone, China will stay in business: all of those surplus industrial goods will flow to the next biggest developed economies, i.e. those in the EU. American manufacturers, insulated from competitive forces, will only fall further behind, requiring ever higher rates of subsidies and tariffs to stay in business.

But trying to coax the world to join in risks fracturing the global trade system, triggering a destructive trade war that harms everyone. It disturbs me to see the extent to which various economists, some of whom were rightly critical of Trump's tariffs, have twisted themselves in knots to justify Biden's escalation just because he's their guy. Identity politics in the US is a real thing – for many Americans, being a "Republican" or a "Democrat" is a way of life. But it leads many of them to almost blindly follow what their politicians say, regardless of whether their policies make sense. For example, here is "Democrat" and economic commentator Noah Smith repeating the administration's national security argument for industrial policy and protectionism:

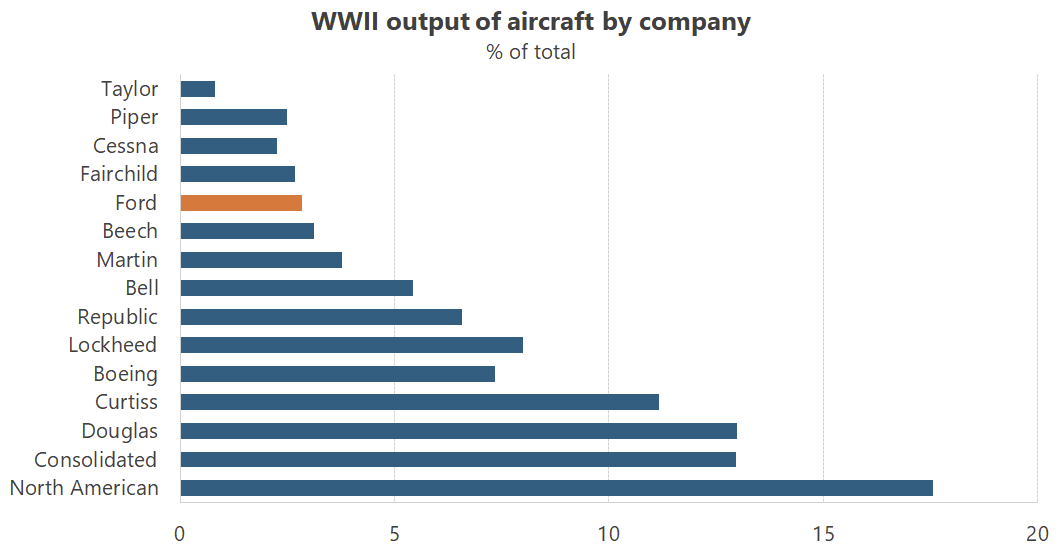

"In times of war, civilian factories are typically repurposed to make war materiel — for example, when Ford churned out massive quantities of B-24 bombers during World War 2. We have a law, called the Defense Production Act [DPA], that allows the government to order U.S. companies to switch their production lines to make military equipment or other goods critical to national security (for example, we used the DPA to make companies build ventilators during Covid).

But the DPA is useless if you don't have the factories to repurpose. If U.S. heavy manufacturing withers and dies in the face of Chinese competition, the U.S. won't be able to add much to its defense production capacity in a war. That could lead to a swift and devastating U.S. defeat at the hands of China."

National security is of course very important, but it's almost always a poor justification for protectionism. Smith's engaging in a bit of comparative statics to make his point, essentially assuming that without government intervention, US heavy manufacturing "withers and dies" in the face of Chinese competition. There is then no response; no coming back.

But even his own example doesn't necessarily help his argument. During WWII, while it's true that Ford was the only non-aircraft manufacturer to deliver fully assembled aircraft, it only accounted for around 2.8% of production over the entire war.

Yes, a lot of manufacturing capacity was repurposed, such as appliance manufacturers Nash-Kelvinator and Frigidaire building airplane propellers, and the car industry did build over half of all aircraft engines. But it's not like repurposing a car factory into an aircraft engine facility was as easy as flicking a switch:

"When Ford built a facility to manufacture Pratt & Whitney engines at its Rouge plant, its existing tools were only suitable for 10% of the tools needed; the other 90% had to be built new."

Moreover, with most men either working or fighting the war, there wasn't much skilled manufacturing labour that could be repurposed into making aircraft. So unskilled women were called up:

"The biggest source of untapped labour proved to be women. Though aircraft manufacturers were initially reluctant to hire women, women eventually made up roughly 40% of the aircraft labour force, and in some plants were as high as 90%.

...

To accommodate inexperienced female factory workers, a variety of changes were implemented. Processes were broken down into simple steps that unskilled workers could do. Part tolerances were relaxed where possible. Tasks were rearranged to be less physically taxing, and aids like trunnion jigs, which parts could be mounted to and freely rotated, were more widely adopted. Tools were redesigned to make them easier to use."

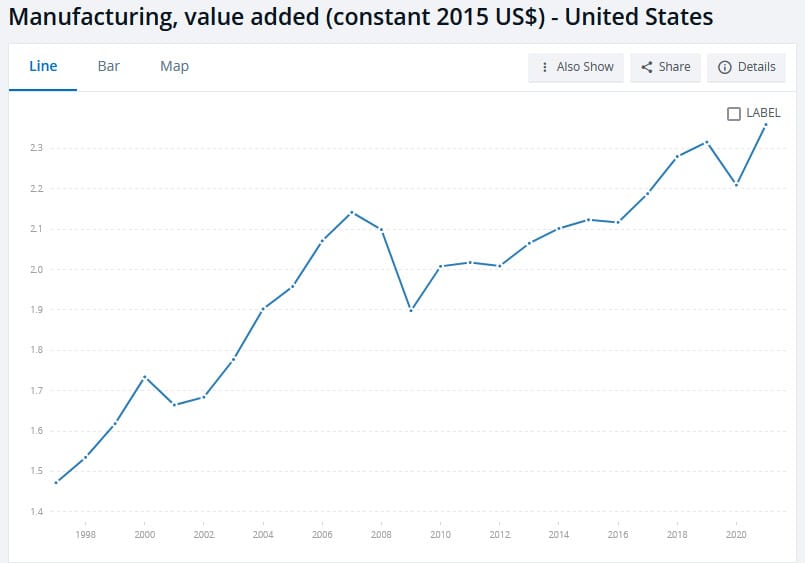

The point I'm trying to make is that in a time of crisis, countries can rapidly adapt and develop new capabilities – both on the labour and capital front. It's also not even clear that US manufacturing as a whole (which is what matters for 'national security') has suffered at the expense of China. In fact, real manufacturing output was doing quite well even before Trump's tariffs and Biden's foray into industrial policy; it turns out the US still produces a lot of stuff:

Sure, if China dominates the market for EVs, they might not be able to assemble electric aircraft (not a thing yet, but could be) as quickly as otherwise. But the US has a large stock of military equipment and is home to one of the world's two leading aircraft manufacturers. It's not like the entire stock of goods would have to be replaced at once; all those Chinese-made solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicles have long average lifespans, often spanning multiple decades.

Yes, there could be a case for encouraging domestic manufacturing of microchips given the risk of a complete reliance on foreign sources, especially from Taiwan given its geographical proximity to China. But not for EVs, batteries, steel, or aluminium. And how, exactly, does Biden blocking Japan's purchase of US Steel thwart China?

If national security was a legitimate concern for Biden, he should use China's manufacturing glut against it. By avoiding a trade war and costly protectionism to sustain uncompetitive domestic manufacturers, Biden could:

- take advantage of the 'free gifts' (cheap goods) China is giving it, reducing prices and increasing economic efficiency;

- focus on his country's comparative advantage and specialise in industries where it has a competitive edge, supported with R&D where necessary; and

- avoid the distortions and inefficiencies that arise from government-led industrial policy and protectionism.

Doing the above would grow the size of the US economy relative to China's, allowing it to support a larger, more technologically advanced manufacturing sector and military. If China cuts the US off at some point, or they go to war, it's at that point that the US can then ramp up domestic production to meet its needs. Industrial policy and protectionism does the opposite: it's wealth destructive and therefore narrows the wealth gap between the US and Chinese economies, reducing the former's advantage.

It's also very hard to get rid of protection once it's in place: in 1954 the US government declared mohair – wool made from the hair of a goat – as a "strategic material", funnelling cash into the industry because it was used in military uniforms. That protection persisted "for almost 40 years until they were repealed in 1993", only to be reinstated in 2002. Ridiculous? Yes. But that's the power of special interests in politics.

The slippery slope of protectionism

Public choice theory teaches us that politicians face their own set of incentives. When you ask "the government" to do something, those incentives will shape the eventual outcome. So while your blackboard might say that in theory government can do industrial policy effectively and in the public interest, the results are often quite different.

Tariffs are a blunt instrument that can create unintended consequences, such as triggering retaliatory measures from other countries, whose politicians are also acting in their self-interest. If Biden succeeds in kicking off a trade war, it may even harm the very industries and workers he's trying to protect, plus the usual side-effects such as higher prices for consumers, reduced efficiency, and less innovation.

But that's the thing about protectionism; it often begets even more protectionism. Already China is considering unleashing tariffs as high as 25% on imported cars with large engines, while the European Commission may impose tariffs on Chinese EVs, although they have ruled out imposing "blanket tariffs" (for now). In a few years when the Hunter Valley solar panel plant gets moving, you can be sure there will be an Australian politician calling for a "response", too.

If Biden was serious about countering China he wouldn't be running fiscal deficits of 6.3% of GDP during a period of strong economic growth, and would instead be ensuring that the private and public sectors are free enough to respond to China, were the need to arise. That's the real risk here; the US is a country that now spends more on interest payments each year than it does on its military, putting it in an unenvious historical position. As historian Niall Ferguson has noted:

"Any great power that spends more on debt service (interest payments on the national debt) than on defense will not stay great for very long. True of Hapsburg Spain, true of ancien régime France, true of the Ottoman Empire, true of the British Empire, this law is about to be put to the test by the US beginning this very year, when (according to the CBO) net interest outlays will be 3.1% of GDP, defense spending 3.0%."

But Biden isn't serious about China; he just wants to portray to the people that he's about as serious as Trump, so that come November those marginal, tariff-friendly voters will stick with him. National security is simply the pretext for Biden's protectionism, motivated by political expediency.

Member discussion