Why real wages had to fall

It's no secret that real wages in Australia have been in the proverbial gutter in recent years. According to last week's wage price index (WPI), wages growth slowed to 0.8% in the March quarter, which if sustained for a full year equates to an annualised rate of 3.3%. Now in normal times that wouldn't be so bad; the problem is we're not in normal times. Inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI), also increased by 1.0% in the same quarter (3.9% annualised).

Net one off the other and for the first time in a year, real wages went backwards.

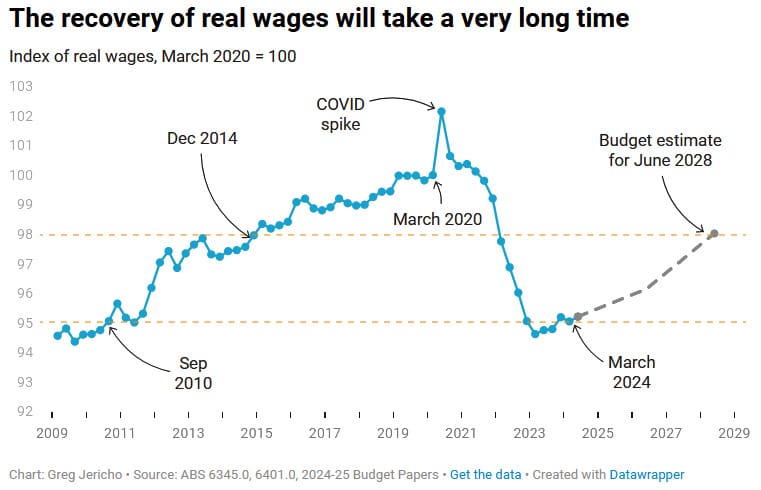

That news generated a few headlines. The most pessimistic of the bunch was from The Guardian's Greg Jericho, who noted the fact that real wages have gone so far backwards that they're now equivalent to 2010 levels:

There's nothing inherently wrong with that chart. But it is wrong to interpret it, as Jericho did, to mean that:

"In effect we have lost 14 years of progress on living standards and, unless real wages grow faster than they did before the pandemic, we shall continue to be that far behind until the middle of next decade."

Jericho's mistake

Jericho's mistake stems from misunderstanding what the WPI and CPI measure. Starting with the WPI, it's not actually a measure of people's wages but a measure of wages for specific jobs. If everyone stayed in the same job forever, then it would be a great proxy for incomes. But they don't, so it's not – in Australia, of our more than 14 million workers, nearly 10% changed jobs in just the past year, and over half of all workers have been at their current job for fewer than 5 years.

The WPI captures some of this effect – for example, if a firm raises wages to poach or retain a worker – but also misses a lot. And the misses can be significant; in Australia, the e61 Institute recently estimated that switching jobs results in a 9 percentage point higher pay increase than if a person stayed at the same job.

Put it all together, and it's likely that the WPI has underestimated nominal wages over the past few years, a quirk that was likely intensified by the pandemic.

As for the CPI, it only captures pure price changes. It does not account for substitution effects, or changes in the composition of household expenditure, so can overestimate how far people's living standards have fallen.

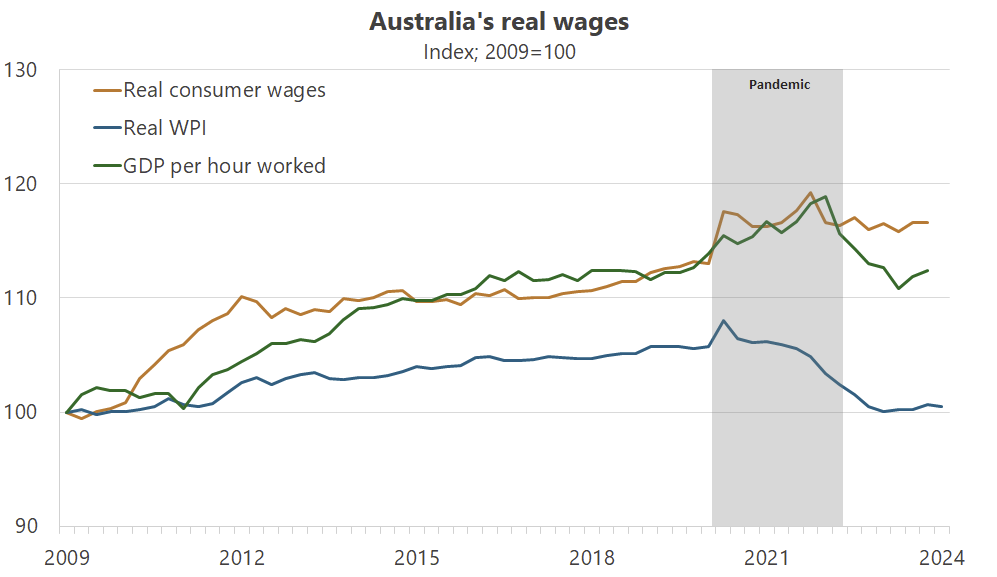

To get a better idea of those changes, we can look at household final consumption, which is a proxy for all household expenditure. If we then use that to deflate total non-farm compensation per worker, which "comprises wages and salaries (in cash and in kind) and employers' social contributions", we get what is known as the consumer wage. In the long run, this indicator closely tracks labour productivity and is therefore a better proxy for living standards than the WPI/CPI measure used by Jericho:

It's true that real consumer wages have gone nowhere in four years. But they're still above where they were in 2010 and are well above labour productivity, which is actually part of the reason we've seen no growth since 2020: when real wages get too far ahead of productivity (such as during a mining boom), they tend to flat-line or fall for a period until the latter catches up, preventing high unemployment. While it would be more efficient for nominal wages to also fall and speed the process up, that's unlikely because "cuts to nominal wages can reduce morale and prompt resistance even in difficult economic times", so businesses tend to adjust by using fewer workers or more capital (and nominal wage cuts are illegal in the public sector).

So, the stagnation of real consumer wages in recent years, and falls in the WPI/CPI real wage, is best thought of as part of the adjustment process to the pandemic and mining boom the global response to it kicked off. When labour productivity catches back up, we should start to see real wage growth again.

Wages do influence inflation

Perhaps Jericho's most egregious claim was that "it is impossible for wages to drive inflation when they are actually rising slower than inflation!".

For the econ geeks reading, you'll recall that inflation can be simplified using the Fisher equation, or MV=Py, where M is the quantity of money, V is money velocity (how many times a dollar changes hands), P is the price level (inflation), and y is real output.

If real wages get stuck above labour productivity then the economy is less efficient, reducing y, or real output. Without a change to M or V, then P (inflation) will be higher than otherwise.

Assuming no change to velocity, the only way Jericho's statement is true is if the Reserve Bank of Australia intervenes and tightens monetary policy (M) to offset the fall in y, preventing P from rising, in which case NGDP declines even further and unemployment is likely to rise.

So yes, it is possible for wages to "drive" inflation if they are, for whatever reason, too far above labour productivity; the current rate of inflation is irrelevant. One way that can happen is if a central wage setting body like the Fair Work Commission, to which around one in four Australian wage contracts are linked, makes a few mistakes and ends up fixing nominal wages at a level too high for the economy to sustain.

In fact, wage indexation – that is, linking wages to consumer prices or some other measure of the cost of living – was part of why inflation proved so difficult to get rid of in the 1970s.

The pandemic made us poorer

Just because the cost of living has increased doesn't mean wages should rise to 'restore' that lost purchasing power. The unfortunate fact is we, as a nation, are poorer now than prior to the pandemic, largely because of the huge transfers and restrictions on activity during that period (paying people not to work). Regardless of whether you think that was worth it or not, it happened, and we paid for it with a combination of borrowing from the future and a bout of unexpected inflation.

The fact that the inflation was unexpected is very important. If the public expected a bout of inflation, they would adjust to it and any inflation-induced cuts to real wages wouldn't be masked by it. Real wages may have continued rising, along with unemployment rates, which thankfully we've managed to avoid so far.

So, contra Jericho, one of the biggest macro risks for Australia is actually if the cost of living crisis starts to infect the wage setting process, and the Fair Work Commission puts more weight on consumer prices than labour productivity. As the Bank for International Settlements recently cautioned:

"When inflation starts affecting the 'cost of living' in a broad sense, it is more likely to take centre stage in price- and wage-setting decisions. This could trigger a dangerous wage-price spiral. Securing low inflation is a powerful antidote to such risk, as in this environment inflation exerts little direct influence on wage growth."

I'm already seeing signs that certain interest groups are trying to make that a reality. For example, on Monday UnionsWA secretary Owen Whittle called for a 7.4% increase in the state's minimum wage, because:

"In the face of rising essential costs of living, there is no greater priority than increasing the pay for low-paid working people, apprentices and trainees."

Everyone wants to see people paid more – especially those on lower wages! But if wages move above labour productivity and stay there for too long, it will be even more difficult for many businesses to pay wages while remaining profitable. Either businesses start to fail, workers start to get laid off, or some combination of the two takes place and we fall into a recession. Most people are then worse off.

The economics of salads

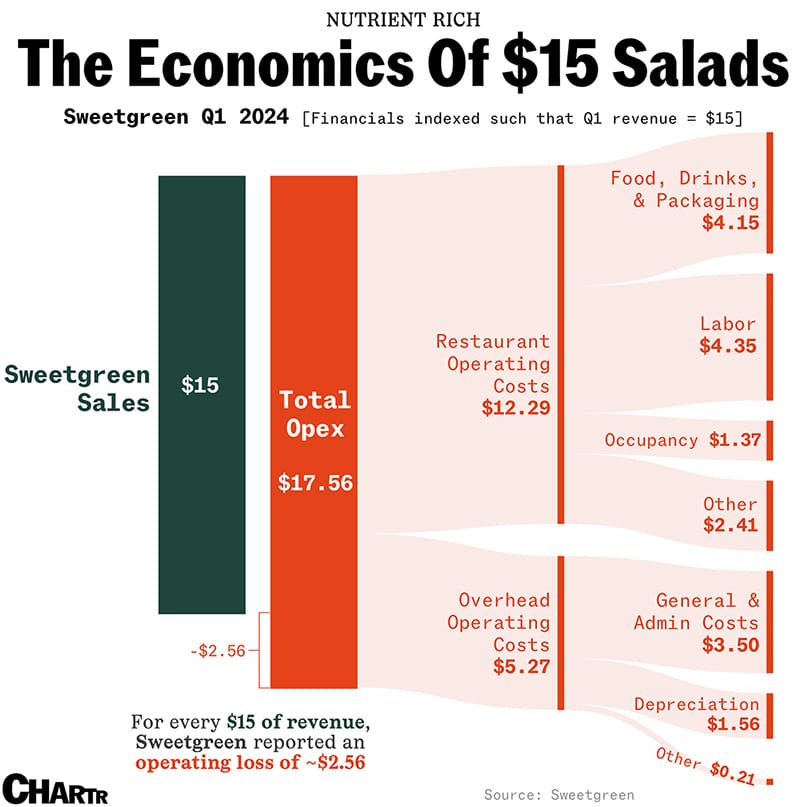

I'm going to end on a slightly odd note: salads. Hear me out. I recently came across an article on Sweetgreen, an American premium salad company. They don't exist in Australia, but in their recent earnings report they provided a very interesting summary of how much they make – or in this case, don't make – from each $15 salad they sell.

The highest cost of selling a salad is labour; it's even more than the food, drink and packaging itself. And if you're Sweetgreen, labour costs are one of the few things within your direct control. If wages rise faster than productivity and labour costs increasingly take up more of your total costs, you need a solution to stay in business – you can't lose $2.56 on every salad you sell for long! In the case of Sweetgreen, it has decided to substitute labour with more capital:

"Last year, Sweetgreen began deploying robots in the kitchen to mix salads, dispense ingredients, and take orders. Indeed, its first automated location opened in Illinois last May, following rivals in the quick-serve sector that were already tinkering with automated stores. That's good for the 'labour' part of Sweetgreen's costs on the chart above… and less good for employment prospects. In fact, the two locations that are automated, which Sweetgreen calls its 'Infinite Kitchens', posted profit margins (at the restaurant level) of 28%... some 10% higher than all of the others, per QSR."

Labour productivity rises when workers and firms invest in capital that is complementary. In this case, Sweetgreen is investing in capital that substitutes for labour, which all else equal will lead to negative employment effects, at least temporarily.

If the Sweetgreen example is replicated across the economy, with wages growing faster than prices – that is, above the marginal product for many workers – then the elasticity of substitution (or in the case of Sweetgreen, automation) increases. Firms will, over time, invest in more capital to substitute for labour, especially if they expect the relative increase in real wages to be permanent. Unemployment will rise while those workers search for their next best employment options, which if it happens on a large enough scale, risks setting off a recession.

What we really need to do, first and foremost, is get on top of inflation. That will help provide businesses with the certainty they need to invest in complementary capital (including in their workers themselves!), which along with economic reform to get labour productivity moving, is the best way to achieve sustainable growth in real wages.

I don't know what Jericho's solutions are, but if we start to see real wages rising again without significant movements in labour productivity, then a wage-price spiral that ends in a painful recession becomes all the more likely. We should tread carefully before backing calls for large nominal wage hikes, regardless of what consumer prices are doing.

Member discussion