Xi Jinping's pivot

I recently returned from a short trip to Hong Kong. The mood on the ground was relatively upbeat—certainly more buoyant than when I visited this time last year—likely due to a recent policy shift in China (more on that in a bit), the large fiscal deficits being run by the government (~6.2% of GDP in the financial year that ended yesterday), and the recent easing by the US Fed which—due to the island's US dollar peg—has slightly loosened domestic monetary policy in what is an interest rate-sensitive, property-heavy economy.

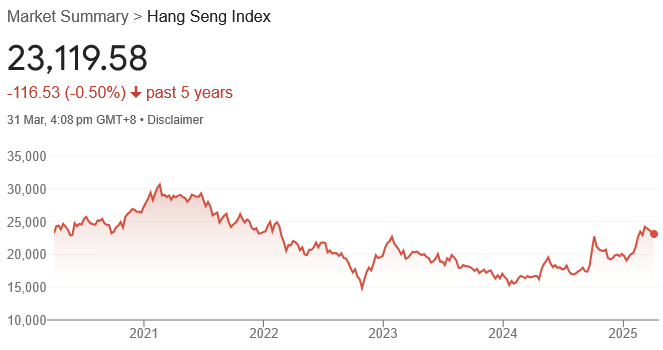

But it has still been a rough few years for the Chinese entrepôt. Its local stock market, the Hang Seng Index, has seen zero nominal returns over the past five years (for context, the ASX200 has grown by 55% over the same period):

It's also struggling to retain its current population, let alone grow: the all-too familiar combo of low fertility rates and an aging population—at 0.72%, Hong Kong's fertility rate ranks only above Macau's 0.66%—has meant its total population has been shrinking.

Years of negative net migration outflows have only added to its woes, although last year it finally bucked that trend—perhaps the result of the city's "talent admission drive"—but only just enough to offset the ongoing exodus of (presumably skilled) locals:

"It seems the government has put more emphasis on attracting foreign talent than retaining home-grown local talent. Could the push-and-pull factors for locals leaving Hong Kong be similar to the reasons for the government's struggle to retain foreign talent?"

But none of that means Hong Kong won't be around for some time. It's more populated than the entire state of Victoria, and is still useful to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—unlike the mainland, the city's capital account is open and people and goods flow freely, making it a good place for Chinese companies to raise offshore capital—so will retain a semblance of 'independence' until China decides to float the renminbi (perhaps never).

But I digress. What I really want to get into today is the mood change in mainland China. Specifically, Xi Jinping's pivot back to the market forces that he had so brutally cut down only a few years ago, and what it might mean for Australia.

The return of the market

In mid-February, Xi met publicly with local tech leaders like Jack Ma, the billionaire he 'disappeared' in 2020, signalling a thaw in his relationship with the sector:

"China's leader urged the assembled founders and CEOs to maintain their competitive spirit and have confidence in the country's future, emphasising that the challenges they faced were 'temporary'. He promised to abolish unreasonable fees or fines against private firms and level the competitive playing field — a common complaint of entrepreneurs in a state-dominated system. On Monday, China's parliament said it would review laws centred on promoting the private economy."

To understand why Xi Jinping is suddenly pivoting back towards the tech sector requires an understanding of his motives. For Xi, there are two concerns that sit above all others: ensuring that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) maintains power; and that Xi himself retains a grip on the CCP.

By 2020, billionaires like Jack Ma had become so successful and popular that Xi felt threatened. Ma's financial group, Ant, was directly competing with state-controlled banks. Private tech companies gathered and controlled vast swaths of data. Meanwhile, state-owned enterprises and all levels of government—largely due to their heavy dependence on the property sector for revenues—were, and still are, struggling amidst a bust for the ages.

Xi perceived the relative success of entrepreneurs like Ma, as compared to the state, as a potential challenge to the CCP's centralised authority—no individual or entity, no matter how successful, can be above the party!

So, Xi spent the next few years—which were interrupted by the pandemic—neutralising the potential rivals whom he believed risked inspiring alternative visions for China's future. Enter "common prosperity", Xi's Mao-inspired slogan for "affluence and prosperity for all, rather than the few", but which was really just a cover for increased CCP control over the Chinese economy.

That goal has now been achieved, but at the cost of economic growth. And just as a private sector that grows too big is a threat to Xi and the CCP, so too is anaemic economic growth, which risks social unrest.

Hence, the pivot.

The special action plan

China's 'special action plan', unveiled in mid-March, focused heavily on raising Chinese consumption:

In his annual speech to China's parliament on March 5th, Li Qiang, China's prime minister, listed 'vigorously' boosting consumption as the first of ten priorities. The state has doubled the size of a trade-in scheme that invites households to swap old appliances, cars and gadgets for new ones. It will also increase the subsidy for medical insurance and raise the basic pension collected by rural people and city folk who do not work from a miserly 123 yuan ($17) a month to a paltry 143 yuan. All told, Mr Li announced extra fiscal stimulus worth 2% of GDP. Although that is better than nothing, it is not quite as much as had been hoped.

Fiscal stimulus is being used because China is mired in deflation caused by a bursting property bubble and its mostly-closed capital account, which—as I wrote last year—means it largely imports monetary policy from abroad:

"China desperately needs to ease monetary policy. But doing so would cause one of two things: a depreciation in the exchange rate, which would probably force a retaliation from the US and other countries with potentially even larger impacts on the domestic economy than the monetary easing itself; or capital flight, which would raise the risk that the current malaise becomes a full-blown financial crisis.

Neither of those are likely to be particularly appealing to Xi Jinping."

An escalating trade war with the US has also brought the existing problems with manufacturing overcapacity to the fore, which Xi Jinping directed following the property bust.

As The Economist summarised:

"Creating a home grown EV industry using subsidies and other government inducements has resulted in severe overcapacity. Chinese factories could perhaps turn out nearly 45m cars a year, equivalent to around half of all global sales, yet they operate at only 60% of that capacity, according to Bernstein, a broker. Oversupply has led to a vicious price war. Seeking an alternative outlet, Chinese carmakers have turned abroad. BYD, Geely and Great Wall have said that margins are five to ten percentage points higher on sales overseas."

According to the University of California's Barry Naughton, the main problem with Xi's desire for "high quality" GDP growth driven by sectors like chips and automobiles is that it's extremely wasteful, especially if producers are increasingly unable to extract higher margins from overseas due to the current protectionist uprising:

"[I]t leads to a massive misallocation of resources, so that the underlying productivity of the economy is basically not improving. When we look at total factor productivity growth, which is the economists' attempt to figure out what you're getting from pure efficiency gains, China's not really experiencing significant productivity growth. That is astonishing, because if we look at this economy that's implementing all these new technologies, we think, wow, that's gotta produce some kind of explosive growth in productivity. But we don't see it.

And it's fundamentally because, for example, China is investing in lots of semiconductor equipment plants that are losing immense amounts of money; it's investing in thousands of miles of high speed rail that go where nobody wants to go. There are just these huge, long run implicit costs from not improving the efficiency of your society."

Fiscal policy is a poor and wasteful tool to get out of such a predicament, even if it might "work" in the sense that it will flatter the aggregates in the short-term:

"A key aspect of policymakers' remedy for dour consumer spending is a trade-in program for a range of goods. The latest data indicated that the scheme is working, with sales of products from furniture to appliances rising."

At best, any 'trade-in' program like this (you might recall that the Gillard government had its own version back in 2010) will simply pull-forward demand with "no evidence of an effect on employment, house prices, or household default rates".

But doing so also comes at a cost—they pull resources from elsewhere and come with large deadweight losses because the money raised to pay for them must be raised by future taxes, which distorts economic activity (a ballpark estimate is around 30% of the amount raised). These programs also destroy perfectly good capital, which lowers a nation's wealth—a good example of Bastiat's broken window fallacy.

Unfortunately for Xi, he can't manufacture his way out of this predicament—he needs market-oriented reform that enables more domestic consumption through higher productivity, not a government-driven "buy China" scheme.

The fact is that manufacturing is only around 25% of China's economy, and manufacturing productivity (i.e. output per worker) remains low—around six times lower than in the US. Even if that were to change, or if China started consuming much more of what it produces domestically, it wouldn't be possible for China to get rich by focusing only on manufacturing. As economist Richard Baldwin has noted:

"China's manufacturing productivity catching up would mean that output per factory worker rose six times. With no reduction in the number of China's factory workers, that would raise world manufacturing GDP by 6 multiplied by China's current world share which is 29%.

That would mean world manufacturing output would rise by about 170%.

Of course, incomes would also rise (output and income are the twin sides of GDP), but since only about a fifth of the new Chinese income would be spent on manufacturing, the induced income rise would have to be radically higher than the 170%. That's impossible in the medium term. And in any case, the number of China's factory workers would surely decline as productivity rose – that's what happened everywhere else (and [is] already underway in China)."

Transitioning to a consumption-driven economy typically requires broader productivity gains to sustain it. That means China's services sector needs to grow both in size and productivity. But you can't get to that point by simply forcing people to consume more locally-produced goods, such as with wasteful cash-for-clunkers schemes—you first need investment (capital) to lift productivity and real wages.

While it's true that China has certainly had plenty of investment, the fact is it hasn't been directed all that well—think underutilised high-speed rail, bridges to nowhere, and manufacturing overcapacity—which is a big part of the reason why productivity has languished.

Even where China's state-directed investment has 'succeeded', for example in its now-dominant ship building industry, it has come at a large and continuing welfare cost:

"[A]lthough China's shipbuilding subsidies were highly effective at achieving output growth and market share expansion, we find that they were largely unsuccessful in terms of welfare measures. The program generated modest gains in domestic producers' profit and domestic consumer surplus. In the long run, the gross return rate of the adopted policy mix, as measured by the increase in lifetime profits of domestic firms divided by total subsidies, is only 18 percent, meaning that for every $1 the government spends, it gets back 18 cents in profitability. In other words, the net return when incorporating the cost to the government was a negative 82 percent, with entry subsidies explaining a lion's share of the negative return."

China's latest schemes might stimulate the official statistics for a while. But in the long-run it's more likely to hold income growth back, as is the case with most of China's government-driven investment and consumption pushes.

Where to from here

China's age dependency ratio – while still low by global standards – has been in reverse since 2010, yet incomes are still well below those of an advanced economy. China is very much at risk of getting old before it gets rich.

But that won't phase Xi Jinping who, as discussed earlier, is much more concerned about the CCP's control over the country (and by proxy, his own power).

That means while he is at the helm, there won't be another heavy dose of economic liberalisation. But that doesn't mean he won't gradually move back in that direction.

And we're starting to see some green shoots. The share of companies in China's private sector ticked up slightly in the second half of 2024, although remains well below its mid-2021 peak. Having now unshackled the tech sector, China is also making great progress on AI, creating large language models running on cheaper domestic chips that are nearly as good as the top American models. Some of its manufacturers, such as BYD, look well placed to dominate the global car market (where they're not tariffed into oblivion).

However, manufacturing has its limits. So-too does the high-tech "new economy", which "has accounted for a little more than 20 percent of growth in recent years", despite huge state-directed investment.

There's also considerable weakness elsewhere in China. First, "most households remain entrenched in deleveraging mode, weighed down by weak confidence in future housing prices and job prospects". And as discussed earlier, the recent attempts at fiscal stimulus and 'rebalancing' the economy towards consumption are unlikely to produce lasting gains because of how it's being conducted.

The uncomfortable fact is that consumption and savings flow naturally from income generation (i.e. productivity); it's a pattern that has been repeated all over the world, many times before. To get there, Xi Jinping needs to get the institutions right—low taxes, stable inflation, and secure property rights—and then allow the market to work.

But at least Xi's recent pivot suggests he's aware of what needs to be done. China State Finance, a Ministry of Finance-backed media outlet, recently warned about the consequences of taking the current approach too far, suggesting he also knows about the limits to fiscal policy:

"[C]ontinued fiscal deficits could lead to a series of problems, including a growing fiscal burden, higher interest rates, and risks of inflation."

But the market will only be allowed to work when it aligns with the CCP's—and Xi's—goals. For now, that means anything that will improve the country's self-reliance (e.g. renewable energy), along with the "new productive forces" in things like electric vehicles, AI, and semiconductors. Many of those sectors use Australian commodities, so there's unlikely to be a major correction that blows up budgets that are now so reliant on mining-related royalty and corporate income taxes.

However, Xi is certainly wary of the old playbook of using debt-intensive investment to boost headline growth, so the process is more likely to be more 'measured' this time around. China is also going to struggle to replace the US as an outlet for its manufacturing overcapacity, which will be increasingly cut off due to the current administration's isolationism and growing protectionism in other countries—even war-torn Russia "is starting to push back against a flood of cheap Chinese imports".

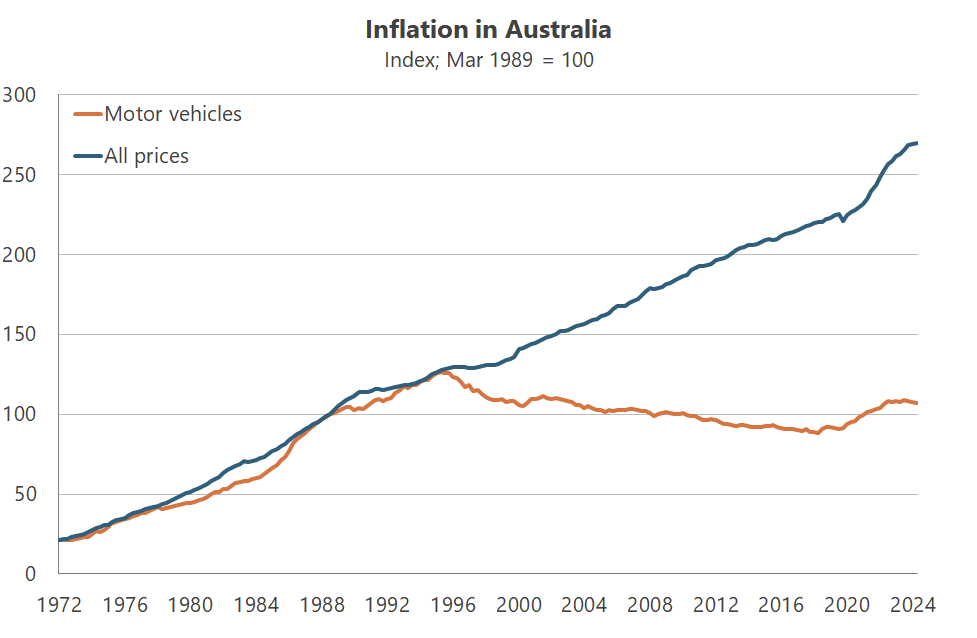

But Australia should welcome these goods. As the gradual reduction of tariffs beginning in the mid-1980s, along with the emergence of Japan as a manufacturing powerhouse, drove down car prices in Australia, China's "new productive forces" will likely do the same for many other goods from AI to semiconductors.

Provided we remain on good terms, i.e. there's no repeat of the 2020 trade dispute or a much more significant blockade or invasion of Taiwan, then Australia is well placed to cash in on China's next wave of state-subsidised innovation—cheap EVs, AI, and all.

Member discussion